80,000 Hours Podcast

Rob, Luisa, and the 80000 Hours team

Unusually in-depth conversations about the world's most pressing problems and what you can do to solve them.

Subscribe by searching for '80000 Hours' wherever you get podcasts.

Hosted by Rob Wiblin and Luisa Rodriguez.

Subscribe by searching for '80000 Hours' wherever you get podcasts.

Hosted by Rob Wiblin and Luisa Rodriguez.

Episodes

Mentioned books

Jun 5, 2020 • 37min

What anonymous contributors think about important life and career questions (Article)

This podcast features intriguing insights from anonymous contributors about navigating work and life. Listeners will discover surprising answers to questions like how talented individuals falter and what underrated paths can lead to success. The discussion spans vital themes like the importance of mentorship, the value of personal growth over prestige, and advice on tackling career-related health issues. It also emphasizes the significance of supportive networks and the balance between guidance and self-discovery in career choices.

Jun 1, 2020 • 2h 39min

#79 – A.J. Jacobs on radical honesty, following the whole Bible, and reframing global problems as puzzles

A.J. Jacobs, a New York Times bestselling author known for his immersive self-experiments, shares his unconventional journey of living by the Bible while advocating for radical honesty. He humorously recounts his adventures in genealogy, creating the largest family tree, and reframing global issues as solvable puzzles. Jacobs explores gratitude through thanking the myriad contributors to his daily coffee and emphasizes the importance of small, actionable goals in health and happiness. His insights blend humor with profound reflections on ethics and personal growth.

5 snips

May 22, 2020 • 2h 12min

#78 – Danny Hernandez on forecasting and the drivers of AI progress

Discover how computation for AI has skyrocketed since 2012, making systems both more powerful and efficient. Dive into the nuances of forecasting AI's future, and why understanding historical data is crucial. Hear about the challenges in gauging expert opinions and the importance of clarity in AI discussions. Explore the Foresight team at OpenAI and their role in tracking AI trends. Lastly, gain insights into the complexities of AI investments and the significance of algorithmic innovations.

May 18, 2020 • 1h 37min

#77 – Marc Lipsitch on whether we're winning or losing against COVID-19

Marc Lipsitch, a renowned epidemiologist and professor at Harvard's Chan School of Public Health, shares crucial insights on COVID-19's current state and the fight against it. He discusses the efficacy of island nations in suppressing the virus while illustrating the struggles faced by others. Lipsitch touches on the controversial idea of intentionally infecting individuals to hasten vaccine development and emphasizes the need for improved pandemic strategies. His analysis of past responses highlights lessons learned for future outbreaks and the necessity of clear communication in public health.

May 12, 2020 • 27min

Article: Ways people trying to do good accidentally make things worse, and how to avoid them

Discover the complexities of well-meaning actions that can inadvertently cause harm. The discussion reveals six common pitfalls in altruism, emphasizing strategic planning and mentorship to avoid negative outcomes. The impact of transformative AI on society is also explored, posing significant risks against potential benefits. Learn about the need for effective communication and collaboration in community initiatives to foster trust and understanding. This deep dive into the paradox of good intentions sheds light on navigating the challenges of creating meaningful change.

May 8, 2020 • 1h 53min

#76 – Tara Kirk Sell on misinformation, who's done well and badly, & what to reopen first

Tara Kirk Sell, a Senior Scholar at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security and former Olympic swimmer, dives into the significant role of misinformation during health crises. She discusses lessons learned from COVID-19 and how media narratives can impact public compliance. Tara critiques U.S. health responses, emphasizing transparency and preparedness for future pandemics. She also explores innovative approaches to risk assessment and the necessity of community involvement in reopening strategies. Expect insightful commentary on the balance of safety and economic activity.

Apr 28, 2020 • 2h 13min

#75 – Michelle Hutchinson on what people most often ask 80,000 Hours

Michelle Hutchinson, Head of Advising at 80,000 Hours and former contributor at Oxford's Global Priorities Institute, shares her unique insights on career planning. She suggests a reverse approach to traditional career advice by prioritizing impactful roles over personal interests. The discussion covers the importance of applying to diverse job opportunities, navigating emotional challenges during job searches, and recognizing personal self-worth beyond professional success. Listeners also learn how to seek effective career guidance and the significance of broadening options for a fulfilling career.

Apr 17, 2020 • 2h 37min

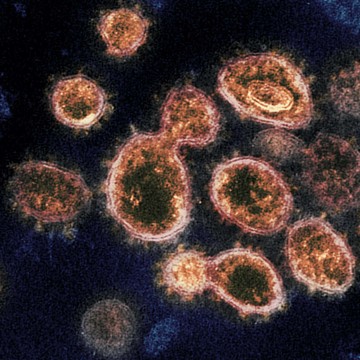

#74 – Dr Greg Lewis on COVID-19 & catastrophic biological risks

Our lives currently revolve around the global emergency of COVID-19; you’re probably reading this while confined to your house, as the death toll from the worst pandemic since 1918 continues to rise. The question of how to tackle COVID-19 has been foremost in the minds of many, including here at 80,000 Hours. Today's guest, Dr Gregory Lewis, acting head of the Biosecurity Research Group at Oxford University's Future of Humanity Institute, puts the crisis in context, explaining how COVID-19 compares to other diseases, pandemics of the past, and possible worse crises in the future. COVID-19 is a vivid reminder that we are unprepared to contain or respond to new pathogens. How would we cope with a virus that was even more contagious and even more deadly? Greg's work focuses on these risks -- of outbreaks that threaten our entire future through an unrecoverable collapse of civilisation, or even the extinction of humanity. Links to learn more, summary and full transcript. If such a catastrophe were to occur, Greg believes it’s more likely to be caused by accidental or deliberate misuse of biotechnology than by a pathogen developed by nature. There are a few direct causes for concern: humans now have the ability to produce some of the most dangerous diseases in history in the lab; technological progress may enable the creation of pathogens which are nastier than anything we see in nature; and most biotechnology has yet to even be conceived, so we can’t assume all the dangers will be familiar. This is grim stuff, but it needn’t be paralysing. In the years following COVID-19, humanity may be inspired to better prepare for the existential risks of the next century: improving our science, updating our policy options, and enhancing our social cohesion. COVID-19 is a tragedy of stunning proportions, and its immediate threat is undoubtedly worthy of significant resources. But we will get through it; if a future biological catastrophe poses an existential risk, we may not get a second chance. It is therefore vital to learn every lesson we can from this pandemic, and provide our descendants with the security we wish for ourselves. Today’s episode is the hosting debut of our Strategy Advisor, Howie Lempel. 80,000 Hours has focused on COVID-19 for the last few weeks and published over ten pieces about it, and a substantial benefit of this interview was to help inform our own views. As such, at times this episode may feel like eavesdropping on a private conversation, and it is likely to be of most interest to people primarily focused on making the long-term future go as well as possible. In this episode, Howie and Greg cover: • Reflections on the first few months of the pandemic • Common confusions around COVID-19 • How COVID-19 compares to other diseases • What types of interventions have been available to policymakers • Arguments for and against working on global catastrophic biological risks (GCBRs) • How to know if you’re a good fit to work on GCBRs • The response of the effective altruism community, as well as 80,000 Hours in particular, to COVID-19 • And much more. Chapters:Rob’s intro (00:00:00)The interview begins (00:03:15)What is COVID-19? (00:16:05)If you end up infected, how severe is it likely to be? (00:19:21)How does COVID-19 compare to other diseases? (00:25:42)Common confusions around COVID-19 (00:32:02)What types of interventions were available to policymakers? (00:46:20)Nonpharmaceutical Interventions (01:04:18)What can you do personally? (01:18:25)Reflections on the first few months of the pandemic (01:23:46)Global catastrophic biological risks (GCBRs) (01:26:17)Counterarguments to working on GCBRs (01:45:56)How do GCBRs compare to other problems? (01:49:05)Careers (01:59:50)The response of the effective altruism community to COVID-19 (02:11:42)The response of 80,000 Hours to COVID-19 (02:28:12)Get this episode by subscribing: type '80,000 Hours' into your podcasting app. Or read the linked transcript. Producer: Keiran Harris. Audio mastering: Ben Cordell. Transcriptions: Zakee Ulhaq.

Apr 15, 2020 • 1h 4min

Article: Reducing global catastrophic biological risks

Discover the looming danger of global catastrophic biological risks and their historical context, from the Black Death to COVID-19. Explore the challenges in recognizing these threats influenced by cognitive biases and inadequate policies. Delve into the complexities of dual-use biological research, focusing on gain-of-function experiments and the need for better governance. Learn how assessing these risks relates to broader existential threats like AI and nuclear dangers, emphasizing the importance of expert consensus and future career opportunities in biosecurity.

Mar 19, 2020 • 1h 52min

Emergency episode: Rob & Howie on the menace of COVID-19, and what both governments & individuals might do to help

In this engaging discussion, Howie Lumpel, a biosecurity and pandemic preparedness expert, joins to share insights on the COVID-19 crisis. They explore alarming projections of potential fatalities and personal health risks. Howie emphasizes individual actions to curb the virus's spread and the critical roles governments must play. The conversation highlights missteps in societal responses and the importance of optimism for future preparedness. Listeners will find valuable resources and actionable advice to navigate these unprecedented times.