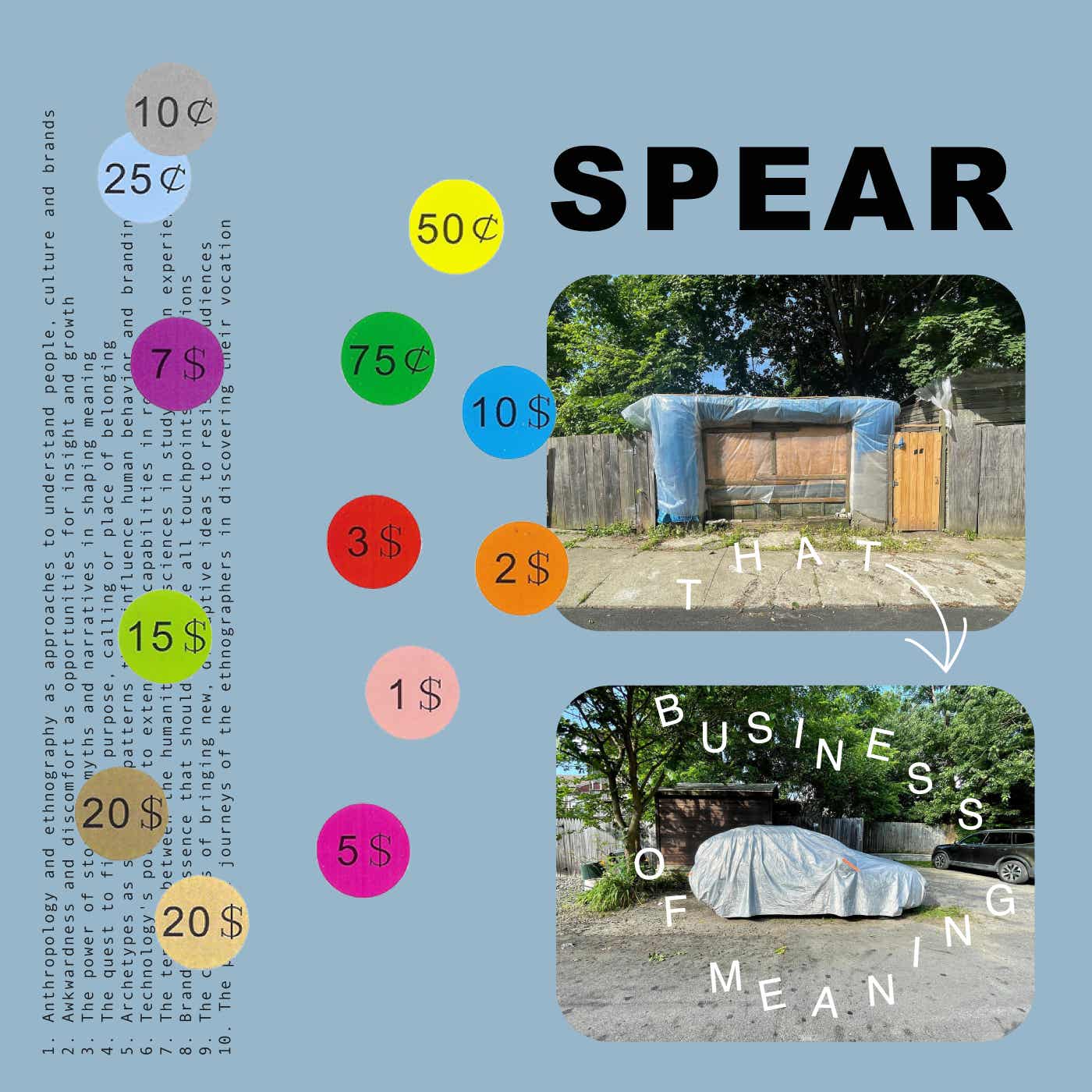

THAT BUSINESS OF MEANING Podcast

Peter Spear

A weekly conversation between Peter Spear and people he finds fascinating working in and with THAT BUSINESS OF MEANING thatbusinessofmeaning.substack.com

Episodes

Mentioned books

Apr 7, 2025 • 48min

Angie Meltsner on Patterns & Insight

Angie Meltsner is a mixed methods researcher and founder of Tomato Baby, where she helps brands decode shifting cultural narratives and consumer behaviors. She has held roles at Blink UX, DraftKings, The Wall Street Journal, Digitas, and Comscore, blending qualitative and quantitative methods to uncover strategic insights.I feel like I’ve been doing this long enough that people might anticipate this question, but I always start my conversations with the same one. It’s a big question that I borrowed from a friend who helps people tell their stories. Because it’s so big, I tend to over-explain it, but just know that you’re in complete control of your answer. The question is: Where do you come from?I listen to a lot of these conversations, and I’ve always wondered how I would answer this if it ever came up. I come from the Midwest, and I’ve noticed that a lot of your recent guests also have roots in the Midwest. I wonder if there’s something there.I was born and raised in Michigan, in a northern suburb of Detroit. My family is very Midwestern—both of my parents were raised in Michigan. My grandparents came from different places, but my grandmother was from the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, so my roots run deep there. I went to college at Michigan State, but I’ve lived in Boston for most of the past 15 years. Still, I definitely identify as a Midwesterner at heart.When do you feel most Midwestern, or what does it mean to be from the Midwest?I feel it in two ways. When I’m in Boston, people sometimes notice my accent, which I don’t even realize I have until I say certain words with long “A’s.” But when I go back to Michigan after a long time away, that’s when I really feel it—I slip right back into that Midwestern mindset.When my family visits me in Boston, I have to remind my mom that she can’t just talk to everybody here. In Michigan, people are naturally chatty; we’ll strike up conversations with anyone. In Boston, it’s different—you keep to yourself more. That difference always makes me feel distinctly Midwestern.I have this image of your mother just saying hello to strangers in Boston. How do New Englanders react to that?They’ll say hello back, but you usually have to be the one to start the conversation. In my early career, I worked on national projects and got to see how distinct regional cultures are—the Midwest, New England, and the West Coast all have their own particular social norms. Boston has much less small talk than Michigan, but most of my friends here are transplants, too. It makes me wonder if that changes my experience of the city.I think you have to do the talking first—you need to be the one to jump in.Early in my career, we worked on national projects, but we also did regional explorations. You really get a sense of how distinct the cultures are in different parts of the country—New England, the Midwest, the West Coast. Each region has its own particular character.Yeah, definitely.I remember doing free association exercises in Boston, and people were just very reluctant to participate.Yeah, there's a lot less small talk. But a lot of my friends aren’t actually from Boston. In fact, I don’t think I have that many friends who are even from Massachusetts. Most of us are transplants—many from New Hampshire or Maine. My husband’s from New Jersey. So my network here is mostly made up of people who moved to the area. I wonder if that makes a difference.What was it like growing up in Michigan? Do you remember what you wanted to be when you were a kid?I really enjoyed growing up in Michigan. It was all I knew because my grandparents lived there—some in the Upper Peninsula, some in Central Michigan, in the Lower Peninsula. But even as a kid, I knew I didn’t want to stay in Michigan. I wanted to live in a city.I didn’t know exactly what I wanted to do, but I was drawn to cities, probably because I grew up in a very stereotypical suburb. Detroit wasn’t a place my parents were comfortable letting me explore on my own, and there wasn’t really public transportation in Michigan—largely because of the auto industry’s influence. So I just dreamed of living in a city, and that became my goal. I think that’s ultimately what led me to where I am now.So how did you make that dream happen?Well, in high school, we had an elective marketing class. If you took the first year and got selected for the second year, you had the chance to go on a class trip to New York City. That’s honestly the only reason I signed up for marketing—I wanted the opportunity to go to New York because I had never been before.And did you get to go?Yeah! I made it into the second-year class and got to go to New York. That experience really stuck with me. My dad, who had a business degree, encouraged me to go into business, so I ended up at Michigan State. I think one of your recent guests—Maggie, maybe?—had a similar experience. She went into a business program right from the start of college. For me, marketing started as just a way to get to New York, but I stuck with it because it seemed like a practical choice. My parents supported it, and it made good business sense as a career path.And I felt like it was business, but creative at the same time. I was really into art and creativity when I was younger—media, design, all of that. Marketing felt like a way to bring those interests together while still feeling responsible and practical. Liberal arts wasn’t really a thing in my family when it came to education, so this path just seemed to make the most sense.Nice. And now you’re in Boston—tell me a little bit about what you’re doing now.Yeah. So I’ve been working for myself for the past two and a half years. But when I first moved here, I didn’t have a job. I just kind of took the leap, moved, and figured it out. I worked as a hostess at a seafood restaurant and at Anthropologie for a while. After that, I started working in ad agencies, moving around a bit to figure out what I actually liked about work. That eventually led me to research—consumer insights, cultural insights. I moved around a bit within that field too, and now I have my own one-person practice. I work with agencies, brands, and all kinds of research projects.What’s the name of your company?It’s called Tomato Baby.What’s the story behind that name?When I decided to go out on my own, I knew I didn’t want to use my own name. I’ve spent my whole life with people mispronouncing or misspelling it, so I didn’t want to make that part of my business. I wanted something fun, creative, and memorable—something that felt like a personal project. I also really love the red and pink color combination, so I was trying to think of something that could incorporate that. Then I remembered this little figurine I have—a Sunny Angel doll. Do you know what those are? They’re these tiny, winged, naked baby dolls, and each one has a different head.I got one a few years ago with a skincare order from an Asian beauty store in New York. I just added it on as a little extra, and the one I got had a tomato head. It’s been sitting around our house ever since, and we always called it the "Tomato Baby." One day, I saw it, and I thought, "Well, it’s red, it’s fun, it’s easy to say and spell—why not?" And that’s how Tomato Baby was born.What’s your relationship with the name now? Did you second-guess it at any point? Because it’s definitely a bold name.Oh, for sure. And honestly, I still do sometimes. In the beginning, I worried—was I going to feel embarrassed saying this out loud when people asked me about my business? But it’s turned out to be super memorable. I once met someone who couldn’t remember my actual name, but they remembered "Tomato Baby"—and that’s all that really matters! If we’re going to work together, that’s what they need to know.I have had people say it doesn’t sound "serious" for a research business, but that’s kind of the point. Research doesn’t have to be dry and boring, even quantitative research, which I do a lot of. Most people love the name, or at least they get it. And if they want to work with me, it gives them an immediate sense of who I am.I think it’s fantastic. It’s such a great name.Thanks!I'm curious about your experience with people misspelling your name. What kinds of mistakes do they make?Yeah, I think it’s because there are four consonants right in the middle—Meltsner, M-E-L-T-S-N-E-R. That combination of L-T-S-N really seems to trip people up. A lot of times, they’ll replace the S with a Z, or they’ll drop one of the consonants. I get Meltzer a lot. It’s been like that my whole life. I’m really proud of my last name—I didn’t change it when I got married because it’s part of who I am. But I also know it’s not the easiest for people to spell or pronounce.That must be frustrating. My last name is unbelievably simple—Spear, like the weapon. My dad used to joke, "Spear as in javelin," and that was enough for people to get it right. I’ve never had to deal with people constantly messing it up. I imagine that would be aggravating.Honestly, it doesn’t really bother me. Well, sometimes—especially when my name is clearly written in front of them and they still get it wrong. But it’s funny, my mom actually changed her last name to Meltsner when she got married, and her maiden name was way more complicated. I won’t share it—for security reasons—but it was long and kind of ridiculous.And then my brother’s wife also changed her last name to Meltsner, and her original last name was this massive 15-letter German name. When they got married, my dad joked that the only people choosing to take on Meltsner were coming from even more complicated names.At this point, I’ve just adapted. I got really good at spelling it out: "M as in Mary, E-L-T as in Tom, S as in Sam, N as in Nancy, E-R." I literally had to do this earlier today. It’s just part of life. My husband, on the other hand, has a super simple last name, and we gave that to our daughter to make things easier for her. But I’m sticking with Meltsner.And how do you help people spell it correctly?I just go into autopilot: "M as in Mary, E-L-T as in Tom, S as in Sam, N as in Nancy, E-R." Works every time.That’s amazing. So, tell me about your work. How do you describe what you do, and what do you love about it?I do all kinds of research, mostly related to consumer insights and cultural insights. And honestly, I’m just so naturally nosy that I can’t believe being nosy is my actual job. That’s how I realized that all these little superpowers and interests I had could be a career.I do a lot of quantitative research—I have a background in survey research—so I make sure that if a survey is being conducted, it’s done properly and for the right reasons. I care a lot about methodology and making sure the approach is actually useful. But I also do qualitative research, especially interviews. And then there’s my semiotics work, which is more about cultural insight and semiotic analysis.That’s actually been the biggest focus of my work since going independent, which I never would have expected when I first struck out on my own. But I love it—I love learning about anything and everything, especially people.Where’s the joy in it for you?Definitely going down rabbit holes. That’s something I’ve done since I was a kid. I grew up with the internet—we got it at my house when I was about 12 or 13—and I spent so much time exploring online subcultures, LiveJournal, weird internet communities. Now, I get paid to do that, which feels kind of unbelievable.And beyond that, I love that I actually get to apply what I learn in my personal life. I used to work a lot with personal finance and financial services clients, and through that, I picked up so much useful knowledge about investing and managing money. It’s like every project expands my perspective in ways I never expected.When did you first realize that this was something you could actually make a living doing? You were in marketing and business—when did research become a real career option?Even in high school, my marketing class included research as part of the curriculum. In college, I took market research and stats-based classes, and I did a lot of quantitative work using statistics. But the class that really stuck with me was consumer behavior. One of the projects involved going into a store, talking to people, and observing them in the space. It wasn’t the main focus of the course, but it planted a seed.Still, when I was looking for my first professional job, I wasn’t specifically thinking about research. I knew I liked it, but at that point, I just needed a job. I ended up at a media buying agency as a receptionist, then moved into media strategy. As I advanced, I realized that the part of my job I loved most was the research aspect.The higher I moved up, the more I was losing that hands-on research work, and that’s when I knew I wanted to pivot. At the time, I was living overseas in London. I made the decision to move back to Boston and focus on finding a research job—something that would let me really dig into the kind of work I knew I loved.What was your first job in research?My first job strictly focused on research was at Comscore, which is a syndicated data company. Before that, I had used Comscore in media strategy as a media measurement tool—it helped with planning media campaigns and assessing audience size and demographics for publishers.At Comscore, I worked on a custom research team. The Boston office came from an acquisition, so it operated a little differently from the rest of the company. Instead of working on their syndicated products, our team focused entirely on custom research. They took a chance on me because of my media experience and the range of clients I had worked with. Once I got into it, I knew—this is where I was supposed to be.And tell me about semiotics. When did you first come across it?At some point in my second career in research, I stumbled upon EPIC. Do you know it?Yeah.Someone had mentioned EPIC to me, and when I checked it out, I found a semiotics course taught by Cato Hunt from Space Doctors. I had probably heard the word "semiotics" before, but it had never really stuck with me. And honestly, I think it’s a shame that I never encountered it in my formal education. Maybe that’s because I was on a business track rather than a communications or humanities track.But when I read that course description, I had this moment of recognition—like, "Oh my gosh, I already think this way. I just need to learn how to do it professionally, with structure." At first, I tried to self-teach. I bought some books and dove in, but I got lost trying to piece it all together on my own. Then I found Chris Arnig’s course, How to Do Semiotics in Seven Weeks, and signed up. The course was designed for UK time zones, and even though they didn’t offer a US-friendly version, I woke up at 3 AM once a week just to take it. That’s how badly I wanted that structured learning. Then, when I went freelance, I happened to meet someone who recognized my interests and potential and started hiring me for semiotics-related projects. From there, it just took off. In fact, for 2024, almost all of my work has been in semiotics or cultural insight.When a client comes to you for semiotics, what kinds of questions are they asking? And how do you explain semiotics to someone who’s unfamiliar with it?A lot of people don’t know exactly what semiotics is or how to explain it, and I’m probably not the best at it either! But at its core, it’s about analyzing the signs, symbols, visual cues, and verbal cues in culture—decoding the layers of meaning that people might not consciously articulate but that still shape their perceptions.A great example: My husband was watching The Founder, the movie about McDonald's and Ray Kroc. There’s a scene where Kroc says something like, "Don’t you understand these golden arches? It’s not just McDonald’s—it’s America. It’s family. It’s tradition." And I turned to my husband and said, "That’s basically what I do."It’s about understanding what these cultural elements mean on a deeper level—beyond just their functional or surface-level associations. A lot of my semiotics work comes through agencies. Their clients have already bought into the idea of semiotics, so I don’t always have to sell them on it directly. But I think that’s one of the biggest challenges—getting companies to understand the value of semiotics in the first place. It’s often seen as a “nice to have” rather than a core research approach, which makes it an easy thing to cut from a larger study if budget pressures come into play. But for the people who get it, it’s incredibly powerful.When I do semiotics work, I typically collaborate with agencies that already have buy-in for the methodology. My role is often to examine how certain cultural questions play out specifically in the U.S. market. It’s so important to understand the cultural context of the market you’re working in.A lot of times, I’ll be representing the U.S. perspective while working alongside colleagues who specialize in markets like China, Italy, Mexico, or India. Together, we analyze advertisements, packaging, retail environments, media, and pop culture—anything from news articles to TV shows and movies. The goal is to spot patterns in the visuals and language being used and understand what deeper meanings they carry.For example, going back to that McDonald’s reference—if we were analyzing a McDonald's ad, we’d ask: What are the visual and verbal codes that represent American culture? How is the "American Dream" being portrayed? We’d gather multiple examples of this idea—maybe ten different representations of the American Dream—and then assess: Which ones are outdated and no longer resonate? Which ones are dominant in culture right now? Which emerging ideas are likely to become dominant in the next few years?By mapping this cultural trajectory, we help clients make strategic decisions about branding, packaging, messaging, and overall brand identity. If they’re rebranding or launching something new, they can align with the most relevant and meaningful cultural cues—or even tap into where culture is headed next.That sounds like a lot of fun.It is! I feel so lucky to do this work. It’s incredibly rewarding.What’s your process like? How do you actually go about doing this?Honestly, it can feel a little chaotic at the start. The first phase is all about collecting. I have a habit of saving things constantly—on Pinterest, in Notion, in random folders. I probably need a better system to centralize everything, but for now, it works.Whenever I see an interesting package, I take a picture. My phone is full of random product photos. I also tag and categorize them, especially in my main focus areas—beauty, personal care, skincare, food, and beverage—since those are the categories I naturally pay the most attention to.When I start a project, I first look at what I already have. Then, I start a deeper dive. I have a huge media list—I subscribe to so many Substacks, though I don’t get any in my inbox. Instead, I keep a list of what I follow and what type of content they cover. If I’m researching food trends, for example, I’ll check Snack Shot to see what Andrea Hernandez has written.I also dig into mainstream media—The New York Times, Washington Post, Wall Street Journal, LA Times. At any given time, I have a subscription to at least one of them. I use Feedly to track publications and search by keyword to see what’s come up across multiple sources.Once I have a wide range of material, I start looking for patterns. The first few days are intense—it’s exhausting and feels messy. I hate sharing my work at this stage because it looks so scattered and chaotic. But then, things start clicking. Patterns emerge, themes become clear, and I can start clustering insights together. And over time, across multiple projects, you develop a sense of where things are going next.Are there broad cultural observations you can make? Since you're working across so many categories, do you see larger patterns—dominant, emergent, or recessive cultural codes?Yeah, definitely. Sometimes that’s actually part of the work—starting with category-specific codes, then zooming out to see the bigger cultural shifts. It’s about identifying what’s residual (fading but still present), what’s dominant (shaping culture right now), and what’s emergent (early signals of where things are headed). From there, we can piece together how these shifts inform the broader cultural landscape.Are there any observations you could share?Oh yeah, for sure. Though I don’t always know what would be surprising or new to people. It probably depends on what else someone is reading. I don’t publish much of my own thinking outside of client work—I have a Substack, but I barely use it.One clear shift I’ve noticed, which others have written about really well, is the broader political realignment happening across culture. Someone I really like is Anu—her Substack, What’s Anu, is excellent. She articulates a lot of these shifts in ways that resonate with what I’ve seen in my own work.Another big theme I keep coming back to is food as a status signifier. Snacks, protein, functional foods, and even things like Zyn and nicotine consumption—all these choices communicate identity, status, and values in ways that feel really interesting. There’s also a growing blur between food and personal care, which keeps showing up in my work.But I totally get what you mean about feeling paralyzed when asked to just share an observation on the spot. It’s like, when you’re deep in it all the time, it can be hard to zoom out and pick the one thing that stands out.I’m curious—how has Zyn specifically shown up in your work?Zyn is fascinating because it’s emerged as a marker of masculinity, but in a really specific way. It’s often seen as a replacement for smoking, but I think it’s more than that—it’s a new way of engaging with nicotine that attracts people who may never have smoked in the first place.What’s interesting is that Zyn actually started in Sweden, where it was initially more popular with women. But in the U.S., it’s overwhelmingly masculine. And not just in the stereotypical “Tucker Carlson/tech bro” way—it’s also really prevalent among firefighters, police officers, and other blue-collar workers.It’s one of those things where, if you track its usage across different groups, you start to see how something as small as a nicotine pouch can become a cultural marker, carrying all these different layers of meaning depending on the context.I remember reading a list of donation requests during the LA fires, and one of the things firefighters specifically asked for was Zyn. That really stuck with me. It’s fascinating to see who’s actually using it—it’s not just the stereotype we often hear in media, the young, right-wing tech guy.Yeah, that’s so interesting. What do you make of that? Why do you think Zyn is showing up this way? Is it about nicotine itself? A replacement for smoking?I think it’s about the nicotine buzz as a substitute for something like Adderall. For people who don’t have access to prescription stimulants, or just don’t want to go through the process of getting them, nicotine offers a similar focus-enhancing effect. It’s accessible, and maybe it feels like a “healthier” alternative to smoking—though I don’t know how much that perception holds up. I’ve never been a smoker and don’t use nicotine products, so I can’t speak from personal experience, but I think accessibility is a big part of it. I have no idea how much it costs, but I imagine that plays a role too.Yeah, that makes sense. I’ve read enough to be dangerous about masculinity and risk, and nicotine carries an inherent sense of risk—or at least, that’s my association. But what about the political shifts you mentioned? Obviously, we’ve all felt this massive change—how has it shown up in your work? Yeah. And just to say—when I talk about “politics,” we’re also talking about something much bigger. I think a lot of people struggle with the word “culture” because it can feel abstract, but I always say this: the Wednesday after an election, the air feels different. That’s culture. It’s something you can’t quite articulate, but you feel it all around you. So when I say politics, I really mean these larger cultural undercurrents. Over the past year, I’ve seen it emerge in so many different ways—things like the rise of trad wives, the resurgence of full-fat or raw milk, all these small choices that, when you put them together, signal something bigger. Is it just a passing trend? Or does it reflect a deeper, more structural shift?I’d love to not talk about politics so much, but it’s impossible to ignore. Anu from What’s Anu wrote a great piece recently on regressive nostalgia, which captures a lot of what I’ve been seeing. I highly recommend her writing—she articulates these shifts so well.Tell me a little about your approach to qualitative research. You’re a triple threat—semiotics, quant, and qual. How do you think about qual?I love being called a triple threat—it’s as close as I’ll get to being Beyoncé!For me, there’s no substitute for understanding the why behind things. A few years ago, I spoke at a conference about mixed-methods research—how using multiple approaches leads to richer, more meaningful insights. Someone in the audience asked me about big data, since a lot of the talks that day had been about machine learning and large-scale analytics.And I said, look, you can infer and assume all you want from data models, but you’ll never really know why something is happening unless you hear people talk about it in their own words. The language they use, the stories they tell—those are the pieces that give meaning to the numbers.That’s what I love about qualitative research. It’s an honor to sit across from someone and hear them talk about their lives—whether it’s something as simple as what they eat, what they drink, what makeup they use, or something as complex as how they run their business. Everything has a story, a reason behind it. And you just can’t get that by looking at numbers alone.I was talking to a college student recently, and she mentioned a class she’s taking on historical imagination. She said they’ve been learning about something called micro-histories, which I think is such a great term. It really just means anecdotes—small, individual stories that tell us something larger about the world.That’s so cool.Right? I love that framing. It’s basically what qualitative research is—micro-histories that help us understand the bigger picture. I’m curious about mixed methods. I always feel like a fraud because I never formally trained in research—I never went to school for it. But “mixed methods” is a real term, right? It’s not just a common noun—it’s more like a proper noun?Yeah, I guess so. To me, it just means using more than one research method in a study. Most people think of it as using both quantitative and qualitative methods, but technically, any combination of methods counts. If you’re doing a diary study followed by in-depth interviews, for example, that’s a mixed-methods approach.In most of my work, a mixed-methods study usually means combining qualitative research with a survey. Sometimes we start with qualitative and then run a survey to quantify the findings, making sure we understand how widespread certain insights are. Other times, we start with a survey, identify surprising or interesting data points, and then use qualitative research to dig deeper. It’s about layering different approaches to get a fuller picture.Do you have any mentors?Yeah, I do.What mentors have you had, if any?My very first boss comes to mind. When I was a receptionist at a media agency, I eventually moved over to the account team, where I first started doing some research using syndicated tools for media strategy. My boss there, Mary McCarthy, really shaped my career early on. I’m still in touch with her, and that job was 15 years ago. She runs her own media planning business now—if anyone needs media work done, she’s amazing.She gave me a lot of independence, a lot of great advice. I still remember word for word some of the conversations we had. She’s the first person I think of when I think of a mentor. But beyond that, I’ve had so many people in my professional circles that I can turn to, and I’m really grateful for that—especially as an independent researcher.I’m sure you feel the same way. When you don’t have colleagues in the traditional sense, you have to actively seek out other people and develop those relationships. That’s been huge for me—not just for my success, but for my sanity.And the second part of this question, which I don’t know why it feels connected, is about touchstones. Are there concepts or ideas you return to again and again?Yeah… well, what do you mean exactly?I guess I think of it like a security blanket. There are times when I get into a project and feel lost or disconnected from my work, and I need something to anchor me. So I go back to certain ideas—maybe metaphor, or motivation theory, or even just re-examining what a brand actually means. Something that reorients me.That’s really interesting. I wouldn’t say I have a theoretical touchstone in that way, but for me, getting out of the house is the thing that resets me. Walking, going to the grocery store, going to the movies—being out in the world. That’s when I think most clearly.I send a lot of voice notes to myself or to people I’m working with while I’m walking. It’s like my brain switches on the moment I step outside. If I try to capture those thoughts in a text, it’s too much—I’d be typing forever—so I just record voice memos. I have tons of them.I love that. I feel like there are all these rabbit holes around the connection between walking and thinking. There’s so much historical precedent for it—monasteries have walking paths for contemplation, and perambulation has always been linked to intellectual exploration.I remember reading a list of requested donations during the LA fires, and one of the things firefighters specifically asked for was Zyn. That really stuck with me. It’s fascinating to see who’s actually using it—not just the stereotype of the young, right-wing tech guy that the media tends to focus on.Yeah, that’s so interesting. What do you make of that? Why do you think Zyn is showing up this way? Is it about nicotine itself? A replacement for smoking?I think it’s about the nicotine buzz as a substitute for something like Adderall. For people who don’t have access to prescription stimulants, or just don’t want to go through the process of getting them, nicotine offers a similar focus-enhancing effect. It’s accessible, and maybe it feels like a “healthier” alternative to smoking—though I don’t know how much that perception holds up. I’ve never been a smoker and don’t use nicotine products, so I can’t speak from personal experience, but I think accessibility is a big part of it. I have no idea how much it costs, but I imagine that plays a role too.Yeah, that makes sense. I’ve read enough to be dangerous about masculinity and risk, and nicotine carries an inherent sense of risk—or at least, that’s my association. But what about the political shifts you mentioned? Obviously, we’ve all felt this massive change—how has it shown up in your work? Did you see it coming?Yeah. And just to say—when we talk about “politics,” we’re also talking about something much bigger. I think a lot of people struggle with the word “culture” because it can feel abstract, but I always say this: the Wednesday after an election, the air feels different. That’s culture. It’s something you can’t quite articulate, but you feel it all around you.So when I say politics, I really mean these larger cultural undercurrents. Over the past year, I’ve seen it emerge in so many different ways—things like the rise of trad wives, the resurgence of full-fat or raw milk, all these small choices that, when you put them together, signal something bigger. Is it just a passing trend? Or does it reflect a deeper, more structural shift?I’d love to not talk about politics so much, but it’s impossible to ignore. Anu from What’s Anu wrote a great piece recently on regressive nostalgia, which captures a lot of what I’ve been seeing. I highly recommend her writing—she articulates these shifts so well.Tell me a little about your approach to qualitative research. You’re a triple threat—semiotics, quant, and qual. How do you think about qual?I love being called a triple threat—it’s as close as I’ll get to being Beyoncé!For me, there’s no substitute for understanding the why behind things. A few years ago, I spoke at a conference about mixed-methods research—how using multiple approaches leads to richer, more meaningful insights. Someone in the audience asked me about big data, since a lot of the talks that day had been about machine learning and large-scale analytics.And I said, look, you can infer and assume all you want from data models, but you’ll never really know why something is happening unless you hear people talk about it in their own words. The language they use, the stories they tell—those are the pieces that give meaning to the numbers.That’s what I love about qualitative research. It’s an honor to sit across from someone and hear them talk about their lives—whether it’s something as simple as what they eat, what they drink, what makeup they use, or something as complex as how they run their business. Everything has a story, a reason behind it. And you just can’t get that by looking at numbers alone.I was talking to a college student recently, and she mentioned a class she’s taking on historical imagination. She said they’ve been learning about something called micro-histories, which I think is such a great term. It really just means anecdotes—small, individual stories that tell us something larger about the world.That’s so cool.Right? I love that framing. It’s basically what qualitative research is—micro-histories that help us understand the bigger picture.Yeah, totally. There’s something about the rhythm of walking that makes ideas flow.And it reminds me of this weird fact about English gardens—some of those labyrinths they designed were actually a form of entertainment. They would include “whoopsies,” which were little bumps meant to trip you up, keeping you alert as you navigated the space.That’s fascinating. I’d love to dig into the history of the garden labyrinth. I actually came across a book recently called Walking as a Form of Research. I haven’t read it yet, but I was immediately like, yes, that makes total sense. Walking is such a big part of my research process. I see things when I’m out in the world that spark connections to whatever project I’m working on. And if I ever feel stuck—or even when I don’t—I try to make time to step outside.Where do you go? Can you walk right out of your house?Yeah, I live in a city—technically Somerville, which isn’t municipally part of Boston, but it’s right next to it. It’s small, just four square miles, and I don’t have a car, so I’m always either walking, taking the bus, or hopping on the T.When my daughter was in preschool, I had a routine where I’d take the bus with her across town and then walk back—a 45-minute walk. If I picked her up, I’d walk one way and we’d take public transit home together. Now we have a much shorter commute, but my general rule is: if it’s under an hour and the weather isn’t awful, I walk.I’ve lived in the same two-square-mile town for over 20 years, and I never tire of walking the alleys and streets. It blows my mind that it still feels fresh.Yeah, I relate to that. Growing up in the suburbs of Michigan, there wasn’t much to walk to. The big destinations were the video store, an ice cream shop, and—if I was up for a long walk—the public library. But most places required a car.Now, living somewhere walkable, I don’t take it for granted. I can walk or take the T anywhere—to Fenway Park, to amazing museums, shops, parks. It’s not as cool as New York, but it has a lot going for it. And being able to walk home from a baseball game? That’s pretty special.I love that. Before we wrap up, I’m curious about your approach to interviewing. How did you learn to do it? What do you enjoy about it?I started in quantitative research, but I knew I needed to incorporate qualitative—it just fits my nature.Why do you think that is?Maybe it’s the Midwesterner in me—wanting to talk to people. There’s no substitute for that kind of connection. And maybe living in Boston for so long, I started to miss it! So I started adding qual to my research work, reading everything I could find. Steve Portigal’s Interviewing Users is a great book. I also listen to a lot of podcasts and just tried to absorb as much as possible while working on lower-stakes qualitative projects. Then, at my last job before I went independent, I took on a project that involved 30 interviews. I had a partner, so I didn’t do them all, but I did about 20—and that was the moment where I was like, okay, this is it.You learn so much just by doing it. I also make a habit of listening back to my interviews. It’s cringey, but it helps me notice things—like how often I say, Oh, that’s so cool, or, Awesome, thanks! You don’t want to insert too much leading feedback, so I try to be more conscious of that.One of my favorite resources is The Turnaround podcast with Jesse Thorne. It’s all about how great interviewers approach their craft. He interviews Larry King, Jerry Springer, Werner Herzog—just incredible people. Highly recommend it.That sounds amazing.Yeah, it’s so good.Well, this has been a blast. I really appreciate your time.Thank you, Peter. It was a pleasure. Get full access to THAT BUSINESS OF MEANING at thatbusinessofmeaning.substack.com/subscribe

Mar 31, 2025 • 1h 3min

Jason Ānanda Josephson-Storm on Revolution & Happiness