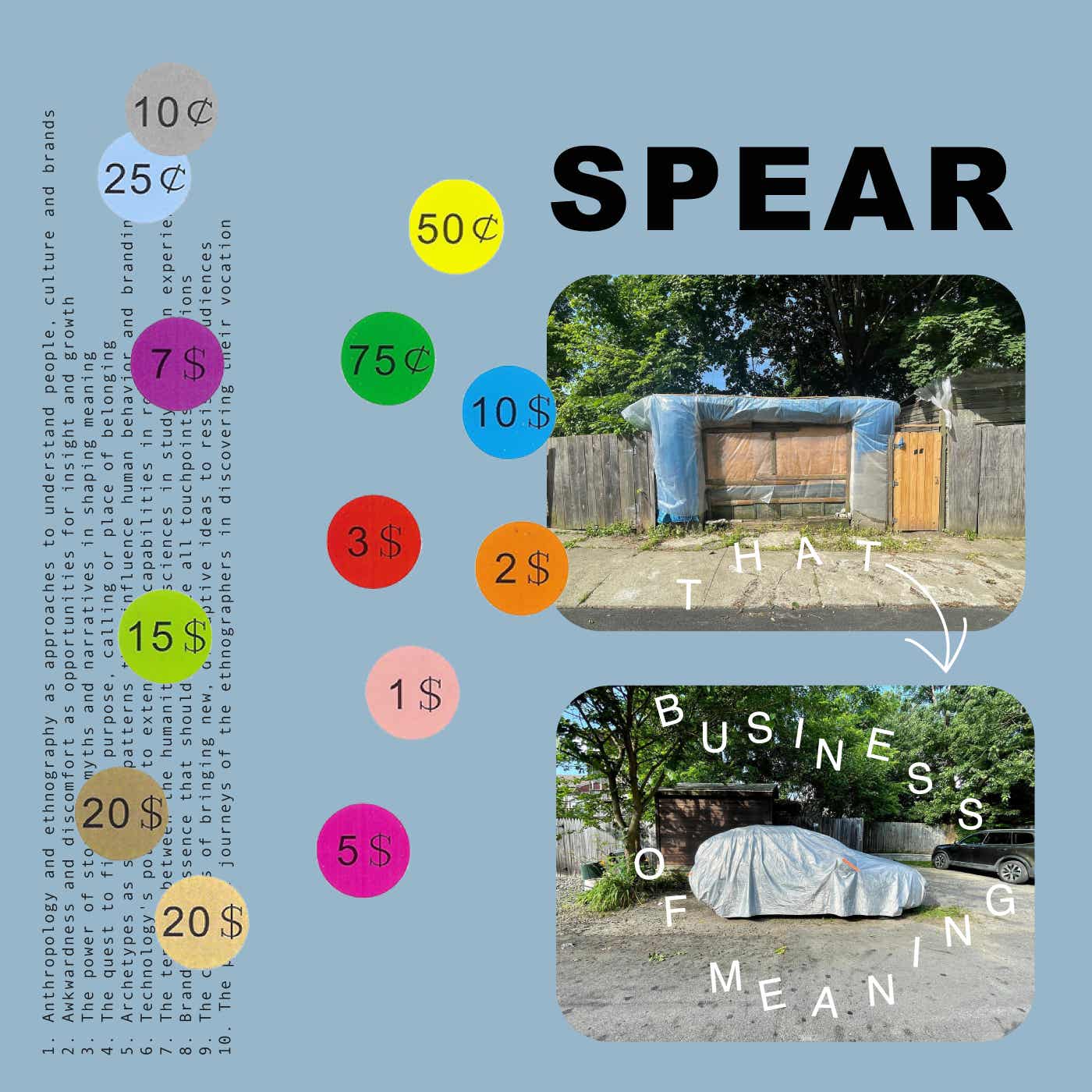

THAT BUSINESS OF MEANING Podcast

Peter Spear

A weekly conversation between Peter Spear and people he finds fascinating working in and with THAT BUSINESS OF MEANING thatbusinessofmeaning.substack.com

Episodes

Mentioned books

Jun 16, 2025 • 53min

Joe Burns on Creativity & Networks

Joe Burns is a Strategy Lead at Quality Meats Creative in Brooklyn, New York. Previously, he was Head of Strategy at BBH USA and Head of Communications Strategy at Mother. I start all my conversations with the same question, which I borrowed from this friend of mine. She helps people tell their story. And I haven't really found a better question for sort of starting a conversation out of nowhere. But because it's so big, I kind of over-explain it the way that I'm doing now. So before I ask it, I want you to know that you're in total control, and you can answer or not answer any way that you want to. And it is impossible to make a mistake. And the question is: Where do you come from?Oh, that’s a great question. It’s sometimes tricky to explain here in the States, where I’m from, because I think the regionalism in the UK is a lot stronger. You know what I mean?Like, sure, it’s strong here too—there’s pride, people wearing their team kits and all that—but I don’t think Americans quite understand how, in the UK, just traveling 30 minutes in a car can take you into a totally different culture.I’m from the Midlands in the UK. And again, that’s hard for people who aren’t British to really get. You’ve got the North, which is culturally cool—a hotbed of creativity, very working-class, very grounded. Then there’s the South, which has always been the well-heeled, posh part—the Downton Abbey kind of vibe.And then you’ve got the Midlands, right in the middle. And if you look at the kind of characters that come out of the Midlands, they tend to be a little... tapped. A bit offbeat. Like Lemmy from Motörhead, or Ozzy Osbourne from Black Sabbath.It’s kind of where heavy metal was born—guys working in factories. It used to be very industrial, very working-class. That’s where I come from—same place as Ozzy and Lemmy. That earthy, middle-of-the-country kind of place.So yeah, I came from there, then went to university in Wales, and eventually moved down to London—kind of a Dick Whittington story.What is it to be from the Midlands? What does that mean for you? When do you feel most Midlands?When I’m eating Marmite on toast. I’m from the town where they make Marmite, so the whole town smells like it—which is a bit weird. But really, there’s something to it. It’s a bit ineffable, hard to pin down. We’re not as... you know—I’m sorry for all the tangents—but I got really into these old Roman accounts of Britain.When the Romans conquered Britain—defeated Boudicca and all that—it was a time when the “civilized world,” Greece and Rome, thought of Britain as a kind of mythical place. A lot of people didn’t even believe it existed—just this island on the edge of the map with white cliffs.Anyway, when the Romans finally went there, their accounts are hilarious. They describe swamp-dwelling, naked, blue-painted people—total savages—just sitting in bogs with nothing on but a spear or a sword.And honestly, I think there’s a bit of that mythical, swampy energy in the Midlands. I definitely feel like I’m a slice of that. I feel most Midlands when I’m in that kind of mindset—swampy, earthy, a bit wild.And do you have a recollection of when you were a boy—what did you want to be when you grew up?Oh, there were quite a few things I moved through, but it always involved ideas and creativity. At one point, I wanted to be a spin doctor for politics. I thought political PR would be good—like, you could combine storytelling with doing something positive. But maybe that was just youthful idealism.So I wanted to do that for a while. But my dream job—and you probably pick this up a bit in the stuff I post and write—was to write headlines for tabloid newspapers.I always wanted to do that. You get a bit of it here with the New York Post, but in the UK, the tabloids are massive. I had a paper route as a kid, and I’d always see the headlines—so clever, with wordplay and a wink. I thought it was brilliant.That’s something I miss about the UK and British culture. You walk down the street and every pub has a funny, well-written sign. There’s this deep appreciation for language.That was really what I wanted to do. Another dream job? I wanted to be the guy who wrote zingers for Arnold Schwarzenegger—not literally him, but for action movies. I was obsessed with those little one-liners: “Hasta la vista, baby.” I loved the challenge of packing so much meaning, cleverness, and humor into a single sentence.So yeah, that was the dream. Sadly, there aren’t many jobs in zinger-writing or tabloid headline writing these days.And catch us up—where are you now, and what’s the work you’re doing these days?I’m in Brooklyn now, part of the strategy team at Quality Meets Creative. We're remote—or distributed, whatever you want to call it—but basically a creative agency that stretches across the U.S.Everyone works remotely. We're small and lean. If you look at how much we put out compared to how few people are doing it, it's kind of surprising. That’s one of the things I love about working here—we’re all prolific. Everyone just loves getting ideas out the door.We’re also really focused on cutting the fat—hence the butcher metaphor in our name. The company was started by two creatives out of Chicago, and it’s still creatively led and founder-owned. That means a lot to me.And maybe this ties back to being from the Midlands—but I’ve always struggled to respect people who were given a title, rather than built something themselves. My granddad on my mum’s side ran a trucking business, and that left a big impression.So I’ve always seen this clear binary—especially in advertising agencies where everyone has a title like VP, SVP, Head of This or That. The way I see it, you’re either the founder and the boss, or you’re... everyone else.I really like being part of an organization where the founders are actually running it. It reminds me of something Tolkien once said—he described himself as an “anarchic monarchist.” I kind of believe in that too: one person at the top, and everyone else is free to get on with things.That’s basically how we work at Quality Meats. The leaders give a nudge—“do more of that, less of that”—but otherwise leave people alone to get things done. That’s my ideal system, and we’ve got something pretty close to it.When did you first discover that you could do this for a living—that you could actually make a living doing it?I had no idea. This is a funny one, man—I just had no idea how advertising worked. As a kid, I didn’t even realize there were companies that made the ads. I thought they just came with the TV shows, you know what I mean?I remember getting a bit older and starting to figure it out—probably did something at school about it—but honestly, I don’t think I knew I wanted to work in a creative agency until I ended up in one.I started working at a digital agency right in the middle of the 2008 financial crisis. Before that, I’d graduated and was doing an internship—kind of a hybrid role, like a digital planner/creative copywriter. Then the recession hit, and the company folded. Everyone stopped getting paid, which didn’t affect me much since I wasn’t getting paid anyway—but no one else got paid that month either.After that, the guy who ran the agency also ran this fashion wholesale/PR/communications boutique. They moved me into that, and I did it for a year. But I really didn’t like the culture. It was very Devil Wears Prada. Even though I was working in menswear, it still had that vibe.I think fashion is one of those industries where the stereotype is actually kind of accurate. It’s a bit of a sycophantic game, and eventually I got tired of it. They paid me next to nothing, so I was couch-surfing—sneaking into the studio to sleep on the floor some nights, staying with friends.One of those friends was like, “Hey, we’re bringing back the grad scheme after a few years. You should apply.” So I did—and I got the job, this time at a media agency. And honestly, it was the best timing I could have asked for.That moment—2008 to 2010—was right when social media, mobile, online video, and the digitization of media were exploding. Especially in London, where the budgets were smaller, it meant more creative thinking was going into these new channels than into traditional TV. I don’t think that really happened in the U.S. until much later.I got a great education. I sat next to the guy who coined the whole “paid and earned” framework. We were doing some of the first interesting work with dynamic creative optimization—not just using it for efficiency, but to actually connect different data stacks. Like, we’d take review database imagery from one place and plug it into campaign assets from another. We were doing stuff that felt cutting edge—maybe even first-of-its-kind.And then one day, I was in a meeting with the creative agency we were working with for HTC—Mother. I impressed them in the meeting, and they said, “Send us your CV, we’ll give you a job.” Six months later, they did. And then I worked at Mother for 10 years.So, to answer your question—when did I know I wanted to work in advertising? I’m not sure I ever really did. Maybe I still don’t. What I do know is that I want to be in a job where I get to come up with ideas that have an impact.And I think creative agencies can do that. That’s also what frustrates me about advertising. People get caught up in the process—like, “We need this many assets and deliverables”—and they lose sight of the actual idea and the outcome we’re trying to create. When it becomes about outputs instead of ideas, it gets really boring. You devalue the work.I want to go back to something you said earlier—you mentioned it was “good for me” to arrive in the industry at a time of transition, from traditional mass media to digital. Can you unpack that? What did that shift do to how you think about creativity or solving problems for clients?Yeah, that’s a great question. And I think we should maybe park this for a second—you can edit it out if you want.But I think those moments of chaos and volatility, when things seem to be unraveling—paradigm shifts, basically—they’re actually fun places to be if you enjoy figuring things out for yourself. And I’ve always liked that: working things out on my own rather than just doing what people used to do, or what the textbook says is the “right” way.I like reading that stuff, engaging with it—but I’ve always been a little insubordinate, you know what I mean? A bit like, well, no, I disagree. I think it works like this.So yeah, it was a really helpful time to come up. And I think it gave me a very specific view on what creativity is really about. Because I think what that transition actually represented—and not everyone’s gotten the memo on this—is a move away from advertising as a kind of cottage industry.What I mean is: a creative agency could come up with an idea, and then spend tons of time, effort, resources, bureaucracy, whatever—refining it into some perfect platonic form. And then they’d stick it into this magical machine called TV. You’d just flip a switch, pour media dollars into the vending machine, and suddenly that perfected little thing reached millions of people—instantly, and with certainty.But that’s not how networked systems work at all. They call TV a “network,” but really it’s like a cloning machine for attention. And in actual networked systems—digital platforms, social media—you’ve got feedback loops, recursion. You can build something fast, put it out there, and either millions of people see it... or nobody does. And it’s all interconnected.So I think I’ve always struggled to think about things in a linear way, because I entered the industry at a time when everything was anti-linear, for lack of a better word. It was like: that old way is done. And yeah, maybe on the media side they over-egged the pudding a bit. I don’t think the creative side fully got it.But it really shaped how I think about creativity—about how it’s done. You’ve got to build things that work in networked systems. If you look at all the successful businesses, they’re the ones that harness network effects—not the ones that just polish one thing endlessly. You know what I mean? Yeah.And what do you love about your work? Where’s the joy in it for you?The real joy of creative work, for me, is examining the mundane—examining the everyday—and thinking about it deeply. Uncovering insights, if you want to call them that, or truths, or whatever. There aren’t many jobs where you get to spend your time thinking about the stuff most people ignore.That’s what I love—finding a new angle on something totally familiar. For me, it’s the opposite of what I think most creatives enjoy. A lot of creatives like novelty—they like making something new. But what excites me isn’t the new thing you make. It’s the old thing you’ve suddenly noticed in a new way.You know what I mean? That’s where the enjoyment is. Like, once you’ve worked on a toothpaste brand, you’ll never look at toothpaste the same way again.Yeah, so how do you go about doing that?Being a good noticer. There are lots of different ways to do it. I think some people are just naturally intuitive—they notice things and think about them without trying.But what I love about it—and this is something QM has kind of codified—is the idea behind one of our mantras: “Dumb in a smart way.” In a way, being good at advertising is about pretending to be a bit dumb on purpose. You know what I mean? It’s about stripping away your assumptions and the stuff you usually overlook, and just observing things with fresh eyes. That’s probably the most effective way to uncover insights.Then there's the other side of it—more relevant when you’re working with data or trends reports—where you have to really put the screws on and ask, What does this actually mean? That kind of rigor is missing in a lot of the industry. People often settle for a superficial read of the numbers.But you can be really good at data analysis just by better understanding what you're actually looking at. Like, if you're a marketer looking at a chart that says:Awareness: 70%. Consideration: 33%. Preference: 12%. Purchase: 5%—if you see that as just a funnel, that’s one read. But if you take a more rigorous, multidimensional view—thinking about the methodology, the exact questions asked, the sample size—you realize how much those details affect what those numbers really mean.To me, that’s crucial: understanding the difference between the map and the territory. Like, we’re looking at a map right now—but that map comes from 2,000 people answering four questions. You’ve got to keep both things in your head: the model and the real world. And maybe be a little skeptical of how well the model represents reality. That’s a hugely important skill when it comes to insights and noticing things.Yeah. How do you do research? Do you have an approach, a methodology, a philosophy? What’s the proper use of qual and quant? How do you begin a process of learning?Usually, I start with whatever I can do quickly. My approach to most things—research included—is based on the mantra: doing stuff beats thinking about stuff.Which is a weird thing for a strategist to say, but I’d rather spend $50 on a quick survey with 75 respondents and three questions, see what it says—then maybe interview three people and record it.I just think iteratively.This is something I think creative agencies still struggle with. When I entered the industry, there was a wave of startups—not just in advertising, but across tech and product. Even at Mother, when I was there, we were investing in a co-working startup space.My manager, the CSO at the time, said, “Joe, I want you to spend one day a week in there with these startups. Hang out, maybe help them.” I think the agency got some equity in return.So I spent a lot of time around startups. And I’ve worked with Facebook, Google, Amazon—all the FANGs except Apple—and until you’ve done it, I don’t think most people understand how much better iterative work is.Bureaucracies and management love to believe they can impose a rational framework on an organization that guarantees great outcomes. But I’m an ultra-fanatic for agile, iterative working. There’s study after study showing how much more effective it is—whether in creative work, knowledge work, whatever.Iterative beats waterfall. Every time.So I bring that to research too. If you’re a client, don’t spend $15,000 on one big study that takes three weeks just to write the brief. Spend $100 testing one thing. Spend $500 testing another.At the end, you’ll have ten times the quality of insight—because you didn’t try to plan your way to a perfect answer, you discovered it through action.Trying stuff. Making stuff. Doing stuff. It’s better than thinking about stuff—even when the goal is better thinking. That’s what blows my mind. Even for thinking, doing wins. So my approach to research is to bake in as much of that as I can. Make it agile. Make it iterative.Yeah. What was your first real interaction with the idea of brand—what it is, what it means?Yeah, that’s… I mean, it’s a tricky one for me because, like I said, I started out in a media agency—not just any media agency, but the global team of one. So I wasn’t even in the part that bought and sold media.When I first joined, I was basically collecting reports and media plans from different countries. Eventually, I moved into the communications strategy team—so more like coms strategy consulting.You know what I mean? Like, how should Nestlé, or Toyota, or L’Oréal—those were all clients I worked on when I was still pretty young—how should they organize their marketing investment?And I’m not just talking about creative assets here. I mean the whole thing. Like when we were launching L’Oréal Men Expert’s Touche Éclat competitor (which I worked on), we weren’t just figuring out where to buy media. We were thinking about shelf placement, what influencer partnerships made sense—all of it.So to me, I’m always a bit baffled when people talk about brand like it’s a TV spot or a logo from a design agency. To me, brand doesn’t exist in objects—it’s the residue of interaction that lives in people’s heads. That’s what a brand is. It’s the sum of everything you’ve done.And the point of brand thinking is really: What are the right touchpoints? Where do they need to be? And what do they need to do to create the kind of residue we want to leave in someone’s mind?What cracks me up is how people talk about TV like it’s inherently powerful. TV is great because of its scale. But on an individual level? If I get a crappy email from a brand with a broken discount code, my perception of that brand drops—more than a thousand TV ads could ever lift it.That’s something creative agencies often miss. TV works because it reaches everyone. But it’s not individually motivating. A bad store experience, a confusing website, a glitchy promo—those things do more damage than TV can fix. And on the flip side, if you walk into a hotel and they hand you cookies at reception? That can build more positive brand equity than a national ad campaign.But agencies and marketers focus so much on TV and paid media because it’s low friction. Everyone knows how to do it. It’s safe. The money goes where there’s the least resistance, not necessarily where the biggest impact is. That’s something we try to challenge at Quality Meats. We always aim to answer briefs in ways that maximize efficacy, not just ease of execution.We’ve done some fame-driving work for Kotex. We’ve done work for Duke Cannon, a men’s grooming brand. And yeah, there are visual assets and video content involved. But the focus is on creating something with real impact—not just something that’s easy to check off a list because it’s familiar.Yeah. What I’m curious about—well, let me ask it this way. You came into the industry during a major shift. And now, maybe we’re in the middle of another big one with AI. I know you’ve written about “the sloppening.” Tell me where you think things are right now—creativity, research, ideas, impact. What are the implications of AI, and how are you thinking about it?I mean, it’s huge. The shift is going to be tectonic. I always think of insights, trends, and forecasting as being a bit like looking at a London Underground map—you’ve got to pay attention to all the different lines and where they intersect. So I’ll give you a few of the big crossover points, the major shifts I see coming.Now, I love a debate—I don’t think I’m right about any of this. This is just what my body is channeling out of me right now.First, I think the economics of content—or, more broadly, the economics of “stuff to see” and “people to see it”—have massively shifted. What’s scarce now is attention. The cost of creating content has dropped dramatically, but the need to cut through and actually capture attention has become much more premium. So: attention has become more scarce, and therefore more valuable.Second, I think we’re going to see massive flattening in some parts of marketing—especially performance marketing. And here’s what’s interesting to me. Let’s say you buy into Zuckerberg’s claim that 95% of what agencies do is irrelevant. I don’t fully agree, but what could happen is that AI completely removes the barrier to entry for performance marketing.So what happens when everyone has access to the same tools and platforms and the playing field is leveled? It means that every other part of the system—especially the parts that have feedback loops or interact with performance—becomes way more valuable.We’ve seen this with a few clients. They’d been doing only performance marketing, but then started layering brand advertising on top. What happened? We saw performance efficiency improve.I remember working on a booze brand a few years ago—we tracked cohorts of people, and when we lifted brand awareness and consideration scores for that group, their performance targeting efficiency went up.So, brand and performance have this interplay. I don’t love the distinction between the two, but it’s a shared language.And when performance becomes cheap and accessible for everyone, the role of brand becomes even more critical. It’s your edge. It’s how you drive down acquisition costs. Brand, in that context, becomes the most important part of your performance marketing mix.That’s a big shift I think we’re going to see.Third, we need to consider what happens when you combine that with network effects—and the “nichification” of everything. In any networked system, you tend to get a “best and the rest” model. One musician dominates Spotify. One movie dominates the box office. You lose the middle tier.I think we’re going to see more of that with content engagement. In the past, everyone might sit down and watch Friends. Then there’d be this healthy middle tier—shows that didn’t dominate, but still reached a decent audience.Now? Maybe people watch one or two big shows from time to time, and the other 80% of their media consumption is fragmented—podcasts like this one, influencer content, niche creators.As a brand, that means you’ve got to be able to operate in that long tail. That’s where people live now. And I think AI is going to accelerate that shift.Let’s use this podcast as an example—what would a really smart brand partnership look like here? Five years ago, sponsoring a niche podcast wouldn’t have even been a realistic consideration for many brands. Now it is. That’s one of the big changes I see AI encouraging: brands playing smart in more fragmented, distributed, and nuanced spaces.But with AI, I think now it is possible. I think brands will be able to produce an audio asset and stick it in front of a podcast for what—$10 a month subscription or something like that? You get what I mean?The media cost will likely be lower too, because the viewership or listenership on that long tail is way lower than on big-budget HBO-type stuff. So there’s this massive widening of accessibility, and AI will teach people how to do it.So yeah, I think we’re going to see this strange “best and the rest” effect really take hold. And I also think that within a couple of years, we’ll start to see ad agencies getting into content production—monetizing that long tail in new ways.Honestly, it blows my mind that we haven’t seen this already. Maybe someone listening to this podcast will reach out and say, “Joe, let’s build this business together.” Who knows?But seriously—look at these agencies with great reputations, like Wieden+Kennedy or BBH (where I used to work). Why wouldn’t they be producing a MasterClass-style series for small business owners—teaching creativity, helping them apply it—now that those owners have tools to execute it themselves?To me, that’s the space ad agencies should be moving into. It’s a scalable solution to the old “cottage industry” problem. Agencies have always been limited by how much a client will pay for a project or retainer. There’s no scale in that. But if you move into content? That changes.I think people are starting to do it. I post a lot on LinkedIn, and I’m seeing CMOs at research firms with podcasts, agency folks building personal brands through content. I think we’re going to see more and more of that. It’s about personalities becoming more prominent—people getting over the cringe of being known on LinkedIn or Slack or wherever.And if BBH or Wieden+Kennedy or Mother or Crispin or whoever doesn’t move into that space—doesn’t offer a distributed, scalable version of what they do to serve the massive long tail of people now creating content—someone else will. And when that happens, they’ll lose out to someone doing something they could’ve done better than anyone else.So yeah, I’d be shocked if we don’t start seeing this emerge—either from agencies or from somewhere else. Maybe even something like this podcast is part of that shift. Do you get what I mean?It’s content that helps marketers—people who want to get better, learn from those with decades of experience. That’s the last big trend I’d call out. To me, it’s the one most people aren’t seeing coming. And agencies aren’t adapting fast enough to meet it.How would you describe what that is—the form you’re outlining here? You’re describing the conditions for a kind of not-yet-realized agency. How do you describe what that is?To me, it’s a mix of content and tutorials—led by recognizable brands or influential people from agencies. It’s educational content. It moves into the realm of learning.Think about it this way: I use a lot of tools—Adobe Suite, for example—to make the stuff I put out now. And I’ve learned a ton just by going to YouTube and watching tutorials.You could also pay to take a MasterClass or a course on someone’s website to learn something like InDesign, right? I’m talking about applying that model to creativity and ideas—aimed at people who could never afford a creative agency retainer, or even a one-off project.But let’s say you’re a small business, and now you’ve got Meta’s new AI ad tool in front of you. Would you pay $100 or $150 a month for something like “Saatchi Lite”—a creative service for small businesses? That might include access to a community forum, weekly video content, trend reports, and brand-building insights.You get what I mean? It’s creativity as a service. And I’m not saying it’s right for every client—but it’s perfect for the long tail. And it’s incredibly scalable. So the agencies that actually do it—and maybe only two or three will do it really well—are going to make bank.I'm curious about your experience with—are they called carousels? That format. I first came across your work through the carousels you've been creating. You’ve been really prolific, and to me, really sharp with all of them. What’s your experience been like? What drove you to start doing it? How has it been received?It’s been received really well—I’ll start at the end there. It’s become pretty popular. It’s been emulated a lot, which I actually kind of like. To be honest, it all started with a few things coming together. One was just putting that “maker mindset” into practice. Practice really is what it’s about.I’m a big believer that until you make something, you don’t really know what you think. You’re just guessing. So for me, it was about turning my thinking into something tangible. You know what I mean? Maybe not something you can pick up and hold, but something that exists—something real.I wanted to write a book. I wanted to produce things that condensed abstract ideas floating around my head into a concrete output. Essays can do that, of course—but they’re not really suited to how people engage with information now, which is mostly on phones. So I asked myself: what’s the equivalent of the essay for a phone?That’s where carousels came in. It was about understanding the channel and the reality of how people use it—which is: they’re just scrolling, diddling around on their phone. So the challenge became: how do I turn an idea into something you can swipe through, that makes you go, "oh yeah, that’s good."That was part of it.The other part was making strategy take its own medicine a little. Like, only a strategist would walk into a room and present 150 dull, dry slides where the big takeaway is: be distinctive, be clear, cut through, engage emotionally.You know what I mean? All the advice we give clients—but somehow forget to apply to ourselves. So this was just me doing that. Saying, okay, I'm not going to prioritize fidelity of thought here. Because essays and books? They’re great for fidelity. They're great for really scrutinizing your thinking and making it rigorous and deep.But with this format, I had to let go of that a bit. Instead, I prioritized distinctiveness. I tried to make the thinking have some snap, some emotional impact.I still like to write. I like talking in conversations like this, or rambling on a podcast. And there’s a place for that. But this is about understanding the medium—how people are engaging—and creating ideas that can live within that.The Achilles heel of the strategist is that we often want to be deeply understood. We want people to get all the nuance.But to succeed on social platforms, you’ve got to be willing to make some sacrifices in terms of fidelity or depth. That doesn’t mean the ideas are shallow. I’m just trying to get to the crisp part—the bit you can actually hold onto. Maybe it’s the tip of the iceberg.Like today, I posted one on Jevons Paradox. I wrote a 2,000-word essay on it. But is anyone going to read a long essay from me on how Jevons Paradox applies to AI and creativity?Unlikely.So I turned it into something they would read—and maybe that opens the door to more. Maybe more people will read it.What’s the paradox?Well, Jevons Paradox—he was the guy who realized that as coal made things more efficient, people didn’t use less of it—they used more.And that’s the link to AI. I think the same thing is coming for creative work. People are panicking about AI reducing the amount of creative work people can do. But if you look at Jevons Paradox, it actually suggests the opposite: AI is going to massively increase the amount of creative work that gets done.It lowers the cost and barrier to entry. Suddenly, you know, John’s Cupcake Store in Brooklyn can produce creative assets and maybe even put $500 a month behind them in marketing. That’s the long tail again—the demand for creativity is going to go up.The need for a big building with 200 people all working on one brand’s campaign—that might fade. But the aggregate demand for creative and strategic thinking? That’s going to skyrocket.Well, isn’t that the same as a concept from traffic engineering? Induced demand?Exactly that.Yeah—most traffic engineers are trained that when traffic is slow, you just add more lanes. But then more lanes create more demand. It’s self-reinforcing.Yeah, that’s exactly it. And the big thing with creativity is, there's potentially infinite demand for it. If you reduce the cost, why wouldn’t you increase supply? There's infinite demand for ideas.But what are the implications on the kind of creativity being demanded? Do you have insights you haven’t already shared?I think it just changes the shape—and the places it shows up. It makes it more worthwhile to think about more touchpoints, in more ways.Like, take my own carousels as an example. With AI, I can now create visual content that lives inside them. It’s not as good as hiring a human to go out and shoot original photos. Not even close. But for something with a 48-hour shelf life? That’s good enough.I’d never go take 15 photos for a post that people will scroll past in two days. But now I can—and I do. That’s what’s coming. Every nook and cranny where creativity can be applied and make something just a little better will start receiving it.And it gets interesting when you imagine the full tech stack getting involved. I use ChatGPT and Midjourney now. They're good—but imagine if one of the big asset management platforms—where brands store all their creative—trained their own AI.You could say: “We’ve booked an Uber for a client arriving from the airport—generate a personalized welcome message from our agency.” That kind of thing. A micro-touchpoint that would’ve been unthinkable before now becomes easy, personalized, scalable.That’s where this is heading.And the big insight I’m working on for a longer piece is this: communications planning becomes one of the most important, if not the most important, parts of what creative companies can offer.It’s always sat between creative agencies, media agencies, strategy groups—everyone has a bit of it. Sometimes it’s called comms planning, sometimes connections planning.But I think it becomes central. Why? Because it’s the one discipline that combines two things. Sophisticated understanding of systems. And the ability—and instinct—to throw a spanner in the system.In a networked world with more systems, and cheaper, faster ways to act in those systems, the comms planning skillset becomes incredibly valuable. It's the ability to say, “How do things work right now?” And “How can we disrupt that in a way that benefits us?”Take an imaginary example. Say you're a company selling stylus pens—the kind you use to draw on tablets. You might say: “People buy this when they start learning graphic design.”But then you realize: no, people buy it when they start any new hobby—music, writing, sketching.So you create a partnership with a music education platform. A creator from that world uses the pen for something unexpected. Suddenly, you’ve found a new user journey. You’ve disrupted the funnel.That kind of thinking—multifaceted, multidimensional, network-aware—is where I see marketing and communications budgets going.And I think the people who are best at that—at spotting systems, finding the leverage points, throwing spanners into the works—are going to be in huge demand. Or… do you say “wrenches” in America?Yeah.I’m just like—spanners. Throw spanners—no wait—throw wrenches into the system. Whatever it is, that’s going to be the skill everyone wants.Beautiful. Well listen, I want to thank you so much. We’ve come to the end of the hour. It’s been a lot of fun. Very nice to meet you. And I really appreciate you accepting the invitation. Thank you.No, it was lovely to chat. It almost felt like therapy in a way.That’s good. I think that’s a sign of success. Thank you. Get full access to THAT BUSINESS OF MEANING at thatbusinessofmeaning.substack.com/subscribe

Jun 9, 2025 • 1h 7min

Martin Karaffa on Identity & Difference