The Creative Penn Podcast For Writers

The Creative Penn Podcast For Writers Researching And Writing Family History Or Genealogy With TL Whalan

Why People Do Genealogy

- Genealogy is the study of lineage starting with oneself and working backwards to ancestors.

- People are fascinated by archaeology for self-knowledge and the thrill of discovering unique family stories.

Start Research With Living Relatives

- Always start genealogy research by interviewing living family members to capture stories before they're lost.

- Then use official records and newspapers to corroborate and extend your family history.

Verify Genealogy Websites Info

- Use genealogy websites like Ancestry.com to collate many records fast, but verify sources carefully.

- Beware user-uploaded information for potential inaccuracies and always seek original records.

Are you curious about the lives of your ancestors? What secrets might be hiding in your family tree, and where would you even begin to look for them? How do you turn dusty records and vague family stories into a compelling book for others to read? T.L. Whalan shares how she researched and wrote a book about her family history.

In the intro, InAudio.com and Spotify for Authors; The Written Word Podcast from Written Word Media; How to sell 1000 books a month [Author Media]; Vetted services from Alliance of Independent Authors, and Reedsy; Writer Beware for scams.

Plus, Ideogram for consistent Characters; Google Notebook LM video overviews; Gothic Cathedrals; The Buried and the Drowned – J.F. Penn.

Today's show is sponsored by Draft2Digital, self-publishing with support, where you can get free formatting, free distribution to multiple stores, and a host of other benefits. Just go to www.draft2digital.com to get started.

This show is also supported by my Patrons. Join my Community at Patreon.com/thecreativepenn

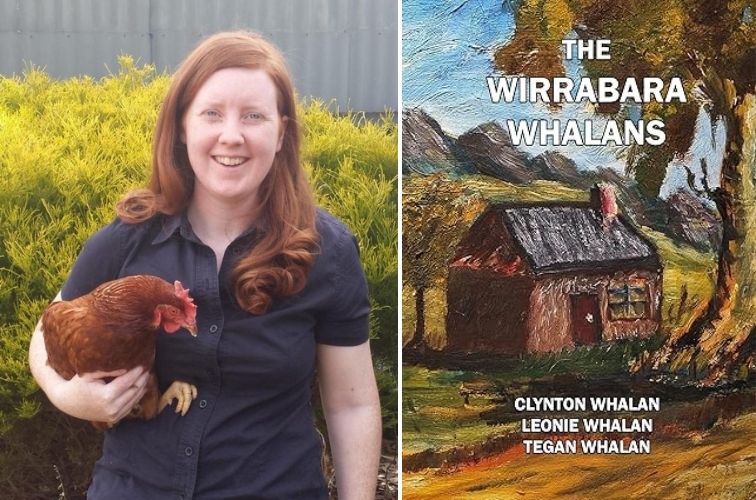

T.L. Whalan is the Australian author of short stories, young adult, and middle-grade fiction, as well as co-author of the family history project, The Wirrabara Whalans.

You can listen above or on your favorite podcast app or read the notes and links below. Here are the highlights and the full transcript is below.

Show Notes

- What genealogy is and the motivations for researching your family history

- Why you should always start your research by interviewing living relatives

- Key resources for research, including official records, newspaper archives, and genealogy websites

- The importance of getting family consent and how to handle sensitive information

- The practical challenges of compiling vast amounts of research and formatting a book

You can find Tegan at TLWhalan.com.au.

Transcript of Interview with T.L. Whalan

Joanna: T.L. Whalan is the Australian author of short stories, young adult, and middle-grade fiction, as well as co-author of the family history project, The Wirrabara Whalans. Welcome to the show, Tegan.

Tegan: Thank you so much for having me.

Joanna: First up—

Tell us a bit more about you, how you got into writing, and also tell us about where you live.

Tegan: Sure thing. It's pretty obvious from my accent that I'm Australian. I live in a town called Hamley Bridge, which has only 700 people. It's a country town north of Adelaide in South Australia. My husband and I chose this country life because of our animals.

We have dogs ourselves, but we also run a dog rescue. Last year we started bottle-raising orphaned lambs, and now we run a dog and lamb rescue. Over the last 15 years, we've re-homed about 400 animals.

In terms of my writing, I was one of those people who always said, “I'm going to write a novel one day,” but never really got around to it. Then, in mid-2014, I decided to get serious.

I Googled how to write a novel and discovered NaNoWriMo (National Novel Writing Month). I thought, “Well, that's good because I can wait until November.” So I did exactly that. I waited until November for NaNoWriMo, wrote a novel that year, and I've been writing compulsively ever since.

Joanna: Just on those bottle-fed orphan lambs. They turn into sheep, right? Do you just have loads of sheep?

Tegan: We've got 10 of our own sheep, which are wonderful pets. They're just like dogs; they run up to the fence and want pets and treats. The lambs that we're raising this year, we are finding good homes for, for them to live out their lives as lawnmowers and lovely pets themselves.

My husband's been very happy since we got the sheep. He hasn't had to mow the lawn, so it's been a good addition.

Joanna: Let's get into this family history project.

What is genealogy and why are people so fascinated with it?

Tegan: There are lots of people who are quite into genealogy or their family history, and it's basically the study of lineage. Often people choose to start with themselves and then work their way back, figuring out who their ancestors are.

I think people are fascinated because we're all a little bit self-centered and want to know more about ourselves. When I'm researching my family tree and find a particularly exciting ancestor, I actually do the math and work out how much of their DNA is in me.

It's nice to know that person makes up part of me. So there's that aspect of learning about yourself that I think is really motivating.

Another part of it is the thrill of the hunt; wanting to knuckle down and find information about these ancestors.

Sometimes when you find a really nice tidbit, you get to the point that you go, “I think I might be the only person alive who knows this about this person.” It's a pretty cool feeling to think that you're at that brink of your research.

I've also done family trees for people in my fiction writing. When I've written historical fiction based on true historical figures, I have been known to make a family tree for that person because I want to make sure that I get it right in terms of their siblings, their parents, their aunties, their uncles, the years of their birth, and how old they would be.

Joanna: You mentioned the research and the thrill of the hunt, but how do you research family history? What are some of the resources people might use?

Tegan: There are lots of resources, but I think sometimes people start in the wrong place. I'm a big advocate of starting with people who are alive now and interviewing them to get those stories. When that person passes, that story could potentially be gone as well.

While I agree it's exciting to get as far back on your family tree as possible, if we can start with living people and the resource that they provide, that's a really excellent starting point.

Once we have all the information we can from living people, we can start to look at other resources. As an Australian, a lot of our ship records are really important. For me, it's free settlers, but for plenty of people in Australia, there are convict records.

We have Births, Deaths and Marriages registries in Australia, which are a valuable resource, though there's a different one in every state, which makes it a little bit complicated.

In Australia, we have a newspaper website called Trove; I think the US equivalent is newspapers.com.

Newspapers have a phenomenal amount of information, like birth and death records, engagement notices, marriages, and sometimes even whole stories about a wedding, which will tell you who the wedding party was and what the bride wore.

We have also had to use Freedom of Information (FOI) to get information about some of our relatives. On my father's side, my great-grandfather was charged with being destitute as an 8-year-old boy and was then in what was fundamentally an orphanage.

We were able to seek freedom of information from the Department of Child Protection to get information about him. We're about to do something similar for one of my relatives who was institutionalized in a mental asylum. So those FOI records can be a valuable resource.

It's a little difficult to give really specific ideas on resources because they are often quite country-specific or even state-specific. For people who are interested, their state-based genealogical center is a good place to start for area-specific resources.

Joanna: Then there are bigger websites too, aren't there? Like Ancestry.com, these more global websites that you have to pay for?

Tegan: Exactly, and they can be a really good resource. They make it their business to collate a lot of records, so you can sometimes search many records quite quickly.

They are useful, but part of the problem with them is that many are user-based, so some of the information is what other users have submitted. Sometimes that's useful, but sometimes that information is inaccurate. There's also the possibility of those inaccuracies spreading through many people's records on those sites.

So Ancestry and other sites are a really good starting point, and we certainly used it a lot to generate hints, but like all resources, you also need to corroborate them and try to access that original source if possible.

Joanna: Being Australian, did you go further back than Australia? Did you end up looking at Britain or anywhere else?

Tegan: Yes, we certainly did. Our ancestors are mostly Irish, and that's who we pursue in this book. We got to the point that we hired a researcher in Ireland for some of our dead ends because if you are in a different country, you are more savvy about the genealogical systems in place.

Knowing locations and their proximity to one another can be really time-consuming. If I were doing that research from here, I would have to have a map app open all the time. Plus, as you mentioned, some sites require payment to access resources, which can be a hurdle in other countries.

We did get an Irish researcher who was fantastic; she managed to get us one generation further back, which was very valuable. There was another one we sent her that she wasn't able to get any further on, which made us feel very satisfied that we were able to get as far as we did.

Joanna: You mentioned freedom of information. If people don't know what that is, can you tell us more about it?

Tegan: With different records, there are different processes in place. With a lot of the ones we've found in Australia, you have to be a very close relation to campaign for those records.

In the case I mentioned with the Department of Child Protection, my father was a direct descendant of that man, which is why he was able to apply for those records. There are different thresholds these organizations require you to meet for them to release that information.

It's certainly worth investigating, and it will be very nuanced depending on the information you're looking for and the organization or government agency you're approaching. A lot of family history is just taking your time and doing things bit by bit.

It might be that an organization has now changed its rules, or enough time has passed. Things often get quite loose after about 100 years, and there's more willingness to release records. It's worth revisiting resources because things can change.

Joanna: You said it's good to start by interviewing family members who are alive. What are some of the questions that you asked?

Was it literally, “What was the name of your mother?” or did you go much wider?

Tegan: We went much more in-depth. When my parents and I started this project for the Whalans, we wanted it to be more than just a person's name, their date of birth, their children, and their date of death. We wanted to know who that person was.

So we compiled 13 questions, which we call the “cousin questions,” and they are available on my blog if anyone wants to see them. A lot of the questions were around location: where they went to school, where they were born, where they lived, where they traveled.

That information becomes really important when you're searching later because it helps to confirm that the person on a record is the one you're looking for. This is particularly relevant if you have a common surname like Smith. We had the benefit that Whalan is not a common name in Australia, which helped our research a lot.

The other questions were about the human story. We asked about people's idiosyncrasies and what they were proud of in their life. That gives you the flavor of a person.

One of my favorite stories we were told was about a man, from his son. He said that his father, when working on the farm, always wore his overalls, and in the front pocket, he always carried a $5 note in case the ice cream truck came by. I just think that's a beautiful way of explaining a person.

It gives you so much more character than his name and dates. You learn he's a farmer, he wears overalls, he must value ice cream, and you learn about the currency and that it was a cash-based society. We learned a lot from that little phrase, and that's the kind of rich color we wanted for our book.

Joanna: What about inaccuracies and corroboration?

How do you know a story like that is true? What do you check and what don't you check?

Tegan: The first part is considering how close the person we're interviewing is to that person. In this particular case, the person telling me the story was his son, and his wife was in the background and laughed, remembering the story with him. So that gives me confidence that it's true.

We can also try to find other evidence. For example, a couple of older ladies told us their father lived in Yundi because of some kind of government chicken farm. They couldn't give me more details, but that sent me on a research journey.

I was able to find out that Yundi was set up by the government to teach impoverished families how to farm chickens. So that vague comment was steeped in truth. All those resources I've already talked about can be helpful in finding and corroborating those threads.

Also, if you interview multiple people, you can often get several versions of the same story. When we produced this book, we sometimes used direct quotes. In that way, we're not necessarily describing it as an absolute truth; we're describing what someone has said about these people, which again gives an impression of a person.

Joanna: How far back did you get?

Tegan: For The Wirrabara Whalans, we go back to 1810. It was a happy surprise that we managed to get ourselves back to 1810, to be honest. That ancestor, born in 1810, immigrated to Australia in 1855.

Joanna: How did the family feel about you making a book that is publicly available?

A lot of people don't particularly want to talk about their family.

Tegan: Overwhelmingly, the response has been pretty positive, and the ones that haven't been positive have been neutral, so that has been a success.

When we were interviewing people, my father, who is quite well connected with the Whalans, could call them up, introduce himself, and get an interview. I had the more difficult job of cold-calling a branch of the family we haven't been actively involved with. I had about a 50/50 success rate.

For those people who weren't willing to help, we respected that choice. A lot of people think they don't have anything to contribute, but almost everyone we interviewed would start with, “Well, I don't know much,” and then they would know quite a lot.

One of the decisions we made early on was that we were only going to feature people who had passed away. This meant we didn't have as much conflict as if we were presenting living people, and there were also privacy concerns.

Another way we protected ourselves was that once we had completed a chapter about their loved one, we gave them that chapter to review. We asked them to look over it and let us know if there was anything they wanted changed. Every now and then, there was a sentence or two they wanted to remove.

Family is important to us, so if someone was uncomfortable, we deleted it. In a 450-page manuscript, a sentence or two isn't going to make a big difference.

Joanna: Was there anything that came up with your family history that was surprising?

Tegan: The most shocking parts involved a lot of bar fights. The one that always shocks me was a bar fight described in a newspaper where one of my relatives broke another man's leg. The force you'd have to use to do that is just horrific to me.

That made it into the book. It's all readily accessible details from newspapers, not new things that aren't already in the public domain.

The nicest surprise was when we managed to go back one extra generation. We found a funeral notice for a woman that turned out to be my three-times great-grandmother.

Later, we were able to corroborate that with DNA; my father's DNA matched with someone with her same surname, which as far as we are concerned, confirms it. That was a very satisfying part of our journey.

We also found with DNA that my dad's uncle had an illegitimate child. We were able to confirm the name of that child through DNA. We knew they existed and had an idea of their name, and the DNA match confirmed it. It was another way we had two resources saying the same thing.

Joanna: How did you handle permissions for photos and newspaper articles?

Tegan: There are a lot of images in the book. Many come from state libraries, which often allow you to use an image if you attribute the source and it's no longer in copyright. We purchased the occasional image from international library collections.

My parents drove all around South Australia taking photos of gravestones, so those are all our own images. There were also lots of family photos donated by family members who gave us consent to publish them.

The newspaper articles often appear in the book in full. They might be slightly fixed up if there are glaring errors, but for the most part, they're reproduced as they appeared and are fully credited.

It was really important for us to make a valid resource, so the book has a bibliography and references for most things throughout.

Joanna: How did you keep everything organized?

It sounds like a huge amount of work.

Tegan: It was a huge amount of work. I was working with my parents on this project, and we live geographically separated, so we had to use online ways to communicate and store information. We used Ancestry.com.au for a lot of our research collation because we could both access it from our different locations.

My parents did a lot of the research, and I did some research while also doing a lot of the formatting and writing. Almost from day one, I had a document that I was adding information to. It was basically one document that just kept growing and growing into the 450-page manuscript it is now.

Joanna: How do you get a family tree into a book? Does it have to go across multiple pages so the font isn't tiny?

Tegan: It was such a painful experience doing these family charts. From the early days, I knew I wanted a family chart for every family at the start of their chapter. I searched online for programs that could do it, but basically all of them fell down once I got to a family with 13 children.

As a result, the family charts in our book were all handmade in Word. That meant I could have a lot of control over the colors, the font, and the readability. It was a lot of work, and I actually had two family members help me with the formatting.

Those family tree charts were a nightmare, but they are very readable and look just how I wanted them to. So that's a small win, but there was a lot of pain to get there.

Joanna: Why did you decide to make the book commercially available? Are people who aren't in your family buying it?

Tegan: We did a lot of work on this project, and we want people to learn not just about our family, but about all the aspects that fed into our family. We sometimes liken this book to being a history of the mid-north of South Australia.

The index we compiled is enormous, and if someone has a mid-north name, you can probably find it in there because many of the same families were moving around the area. This means we do get interest from people who just have a connection to the mid-north, not necessarily the Whalan family.

Most of our book sales have been to family, which is what we expected, but we do sell some to others. We recently attended a market in a small country town about a three-hour drive from Adelaide, and we sold six books. For a very niche family history book, we were really happy with that.

A lot of people were buying it because they know a Whalan, or they have a connection to the mid-north. A lot of the book is about the pioneering days and the shepherd lifestyle in that area.

The book is also in all the libraries we have to supply in Australia, plus some extra ones. We've also made donations of the book to some of the organizations we used in our research to make sure that information is preserved in their records.

Joanna: Tell people where they can find you and this book and everything else you do online.

Tegan: My website is TLWhalan.com.au. You can also find me on Facebook as T.L. Whalan.

The Wirrabara Whalans is my only book at the moment, but I am working on a young adult fiction series, which will appear in all those places once I get around to it. I've been busy with all the animals and bottle-feeding lambs four times a day!

Joanna: Well, look, it's been lovely to talk to you, Tegan. Thanks so much for your time.

Tegan: Thanks, Jo.

The post Researching And Writing Family History Or Genealogy With TL Whalan first appeared on The Creative Penn.