The History of the Christian Church

Pastor Lance Ralston

Providing Insight into the history of the Christian Church

Episodes

Mentioned books

Apr 2, 2017 • 0sec

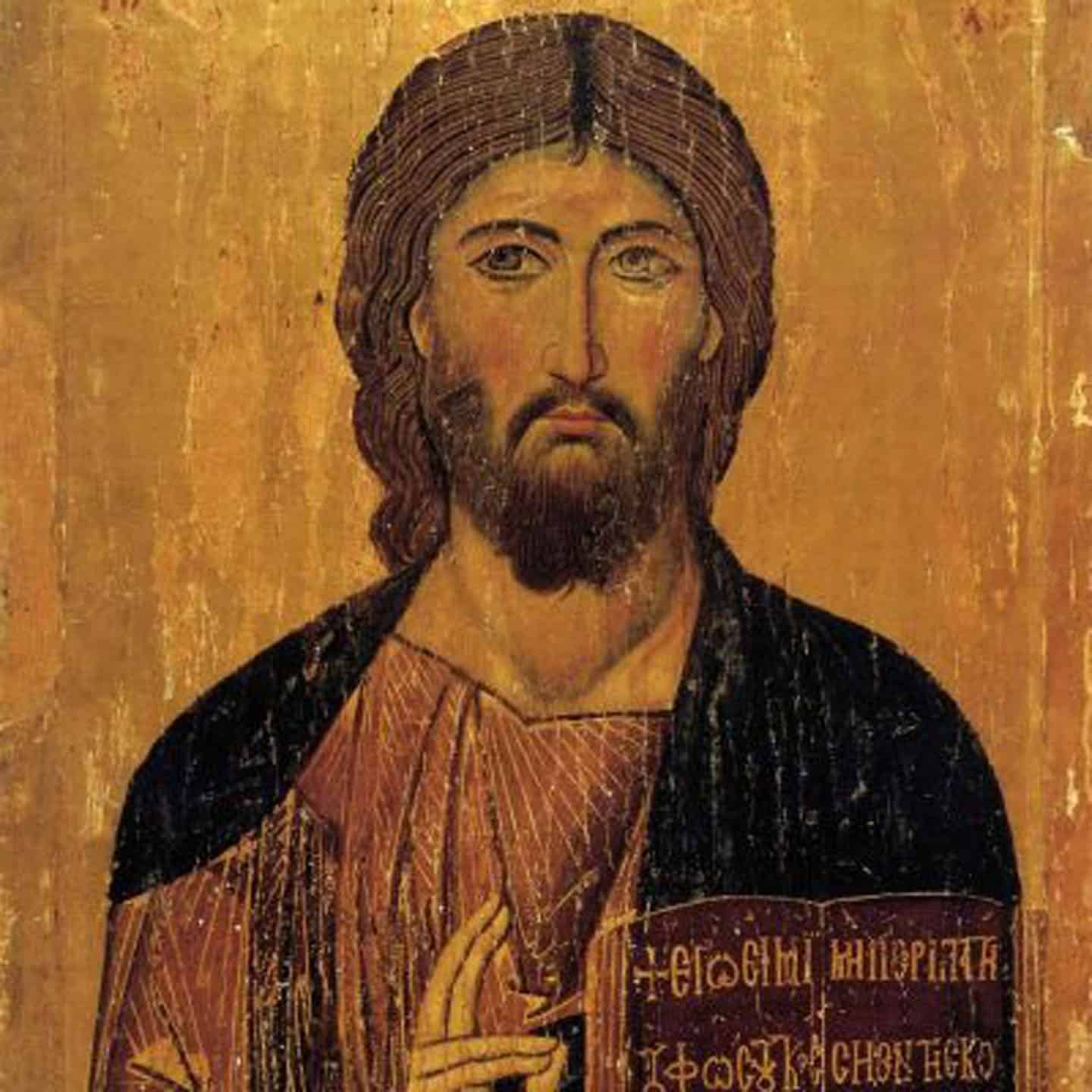

The First Centuries Part 08 – Art

This episode is a bit different from our usual fare in that it’s devoted to the subject of art in Church History. It’s in no way intended to be a comprehensive review of religious art. We’ll take just a cursory look at the development of art in the early centuries.Much has been written about the philosophy of art. And as anyone who’s taken an art history course in college knows, much debate has ensued over what defines art. It’s not our aim here to enter that fray, but instead of step back and simply chart the development of artistic expression in the First Centuries.It’s to be expected the followers of Jesus would get around to using art as an expression of their faith quickly in Church History. Man is, after all, an emotional being and art is often the product of that emotion. People who would convert from headlong hedonism to an austere asceticism didn’t usually do so simply based on cold intellectualism. Strong emotions were involved. Those emotions often found their output in artistic expression.Thus, we have Christian art. Emotions & the imagination are as much in need of redemption and capable of sanctification, as the reason and will. We’d better hope so, at least, or we’re all doomed to a grotesquely lopsided spiritual life. How sad it would be if the call to love God with all our heart, soul & mind didn’t extend to our creative faculty and art.Indeed, the Christian believes the work of the Holy Spirit after her/his conversion, is to conform the believer into the very image of Christ. And since God is The Creator, it’s reasonable to assume the Spirit would bend humanity’s penchant for artifice to serve the glory of God and the enjoyment of man.Scripture even says we are to worship God “in the beauty of holiness.” A review of the instructions for the making of the tabernacle make it clear God’s intention was that it be a thing of astounding beauty. And looked at from what we’d call a classical perspective, nearly all art aims to simply duplicate the beauty God as First Artist made when He spoke and the universe leapt into existence.Historians tend to divide Early Church History into two large blocks using The First Council of Nicaea in 325 as the dividing line. The Ante-Nicaean Era runs from the time of the Apostles, the Apostolic Age, to Nicaea. Then the Post-Nicaean Era runs from the Council to The Medieval Era. This was the time of the first what are called 7 Ecumenical Councils; the last of which, is conveniently called the 2nd Nicaean Council, held in 787. So the Ante-Nicaean Era lasted only a couple hundred yrs while the Post-Nicaean Age was 500.It would be nice if Art Historians would sync up their timelines to this plan, but they divide the history of Church Art differently. They refer to Pre-Constantinian Art, while From the 4th thru 7th Cs is called Early Christian Art.The beginnings of identifiable Christian art are located in the last decades of the 2nd C. Now, it’s not difficult to imagine there’d been some artistic expression connected to believers before this; it’s just that we have no enduring record of it. Why is easy to surmise. Christians were a persecuted group and apart from some notable exceptions, were for the most part comprised of the lower classes. Christians simply didn’t want to draw attention to themselves on one hand, and on the other, there wasn’t a source of patronage base for art in service of the Gospel.Another reason there wasn’t much art imagery generated before the 2nd C is because early generations of believers were mostly Jewish with a long-standing prohibition of making graven images, lest they violate the Commandments against idolatry. By the mid 2nd C, the Church had shifted to a primarily Gentile body. Gentiles had little cultural opposition to the use of images. Indeed, their prior paganism encouraged it. They quickly learned they were not to make idols, but had no reluctance to use images a symbols and representations to communicate the Gospel and express their faith.The style of this early art is drawn from Roman motifs of the Late Classical style and is found in association with the burial of believers. While pagans generally practiced cremation, the followers of Jesus shifted to burial as an expression of their hope in the Resurrection. So outside Rome’s walls near major roadways, numerous catacombs were excavated where Christians both met when the heat of persecution was up, and where their dead were interred. Some of the oldest of Christian imagery is a simple outline of a ship or an anchor scratched into the wall of a crypt. Both were symbols of the Church. The anchor is drawn from the NT Book of Hebrews which refers to the hope of the believer as an anchor or the soul. The ship was an apt picture for the Church. A vessel which is IN the Sea, but mustn’t have the sea in it, just as the Church is to be in the World, but the World is not to be in the Church. Another symbol used to make the resting place of Christians was the ubiquitous fish. As burial in the catacombs became de rigeur , families carved out entire rooms for the burial of their members. Bodies were placed in marble sarcophagi which over time were decorated with religious imagery; symbols and scenes drawn from Scripture.Missing from the art crafted by Christians at this time are the scenes that will later become common. There’re few Nativity motifs, fewer crosses, and nothing depicting the resurrection. That’s not to say Christians in this early era didn’t regard the cross & resurrection as central to their faith. The writings of Ante-Nicene Fathers make it clear they did. It’s just that they hadn’t made their way into artistic expression yet. Rather than pointing DIRECTLY at Christ’s crucifixion & resurrection, artists instead used OT stories that foreshadowed the Gospel. Images of Abraham sacrificing Isaac, Jonah & the fish, Daniel in the lion’s den, Shadrach, Meshach, & Abed-Nego in the fiery furnace, as well as Moses striking the rock are all depicted in frescoes and tomb paintings.The few images of Jesus from the Pre-Constantinian art we see him presented as The Good Shepherd, surrounded either by figures who likely represent the apostles, and symbols from nature, like peacocks, vines, doves and so on.Nothing happened in the way of distinctly Christian architecture until Constantine for obvious reasons. Christians simply could not build their own places. When you’re trying to avoid attention due to persecution, engaging a construction project’s just not wise. But once The Faith was removed from the banned list, and the Rulers of Rome showed the emergent Faith favor, Christians began to shape their meeting places in a manner that maximized their utility, while also adorning them with imagery identifying them as dedicated to The Gospel. The discreet and out of the way places they’d met in before no longer served as suitable meeting places for the rapidly growing movement.After Christianity was allowed to own property, it raised local churches across the Roman empire. There may have been more of this kind of building in the 4th C than there has been since, excepting during the 19th C in the United States. Constantine and his mother Helena led the way. The Emperor adorned not only his new city of Constantinople, but also embarked on a campaign to secure the assumed holy Places in the Middle East. Basilicas Churches were erected using funds from his personal account, as well as State funds. His successors, with the exception of Julian, called The Apostate, as well as bishops and wealthy laymen, vied with each other in building, beautifying, and enriching churches. The Faith that had not long before been a cause of great persecution, became a game to compete in; as the wealthy hoped to earn a higher place in heaven by the churches they raised. Churches became a venue for bragging rights. The Church Father Chrysostom lamented that the poor were being forgotten in favor of buildings, and recommended it wasn’t altars, but souls, God wanted. Jerome rebuked those who trampled over the needy to build a house of stone.It might be assumed Christians would adopt the form for their buildings they were used to as pagans – a temple. Interestingly, they didn’t! Most pagan temples were relatively small affairs intended to hold little more than the idol of the god or goddess they were dedicated to. When pagans worshipped, they did so outdoors, often in a courtyard next to the temple. It wasn’t until the 7th C that believers began to re-purpose some of the larger now abandoned pagan temples for their own use. Even during Constantine’s time, Christians began to use layout of the secular basilica, the formal hall where a king or ruler would hold court.The floor plan of one of these basilicas had a central rectangular hall, called a nave, with two side aisles. The main door was on one of the short sides of the nave, and on the opposite wall was the apse where a raised platform was built for the altar where the minister led the service.During the 4th C saw Rome saw over 40 lrg churches built. In the New Rome of Constantinople, the Church of the Apostles and the Church of St. Sophia, originally built by Constantine, towered in majestic beauty. In the 5th C both were dramatically enlarged by Justinian.As I said earlier, in the 7th C, the now abandoned pagan temples were turned over to Christians. Emperor Phocas gave the famous Pantheon to Roman’s bishop Boniface IV.Anyone who’s been on a tour of Israel ought to be familiar with the term “Byzantine.” Because a good many of the ruins Christian tourists visit are labeled as Byzantine in architecture and era. The Byzantine style originated in the 6th C. and in the East continues to this day. It’s akin to the influence the French Classicism of Louis XIV had on Western architecture.The main feature of the Byzantine style is a dome spanning the center of a floorplan that is cruciform. Let me see if I can help you picture this. Imagine a classic cross laid on the earth. The long bean is the central nave with the cross piece are the transverse sides used as side chapels. Suspended over the intersection of main & cross beams is a dome, decorated with frescoes of Biblically rich imagery.Previous basilicas tended to be flat, blocky affairs; earthbound in their ponderance. The Byzantine basilica lifted the roof and drew the eye to that dome which seemed to pierce heaven itself. The eye was drawn upward. That idea will be perfected centuries later in the soaring ceilings and arches of Europe’s Gothic cathedrals.The most perfect execution of the Byzantine style is found in the Hagia Sophia, the Church of Holy Wisdom in Istanbul. It was built by the Emperor Justinian in the 6th C on the plans of Anthemius & Isidore. It’s 220’ wide, 252’ long; with a 180’ diameter dome supported by four gigantic columns, rising 169’ over the central altar. The dome is so constructed that the court biographer Procopius describes it as being suspended form heaven by golden chains.The cross, which today stands as the universal symbol for Christianity, wasn’t used in artifice until at least the late 4th C. The historical record suggest Christians made the sign of the cross on their foreheads, over their eyes, mouths, & hearts as early as the 2nd C. But they didn’t make permanent images of it till later. And then we find some church father urging Christians not to make magical talisman of them.Julian accused Christians of worshipping the cross. Chrysostom wrote, “The sign of universal detestation, the sign of extreme penalty, has become an object of desire and love. We see it everywhere; on houses, roofs, walls, in cities and villages, in markets, along roads, in deserts, on mountains & in valleys, on the sea, ships, books, weapons, garments, in honeymoon chambers, at banquets, on gold & silver vessels, engraved on pearls, in paintings, on beds, the bodies of sick animals, & the possessed, at dances of the merry, and in the brotherhoods of monks.”It isn’t till the 5th C that we find the use of the crucifix; that is a cross that isn’t bare. It now holds the figure of the impaled Christ.

Mar 19, 2017 • 0sec

The First Centuries – Part 07 – Origen

As I record & post this episode, a new movie’s out called Logan. It’s appears to be the last installment for the venerable X-Men character Wolverine, played by Hugh Jackman. Logan was an immortal who became the subject of a secret military experiment gone wrong. His skeleton was infused with a fictional metal called adamantium that bears the hardness of a diamond. (more…)

Mar 12, 2017 • 0sec

The First Centuries Part 06 / Tertullian & The Montanists

This is part 6 of our series titled The First Centuries, in Season 2 of CS. In the last episode we took a look at the Church Father Irenaeus. This episode we’ll consider Tertullian.That may prompt some to wonder if we’re going to work our way through ALL the church fathers of the Early Church. Uh, no – we won’t. Just a few.While he’s known to history as Tertullian, his full name was Quintus Septimius Florens Tertullianus. (more…)

Mar 5, 2017 • 0sec

The First Centuries Part 05 / Irenaeus

The First Centuries – Part 5 // Irenæus The historical record is pretty clear that the Apostle John spent his last years in Western Asia Minor, with the City of Ephesus acting as his headquarters. It seems that during his time there, he poured himself into a cadre of capable men who went on to provide outstanding leadership for the church in the midst of difficult trials. Men like Polycarp of Smyrna, Papias & Apolinarius of Hierapolis, & Melito of Sardis. These and others were mentioned by Polycrates, the bishop of Ephesus in a letter to Victor, a bishop at Rome in about AD 190.These students of John are considered to be the last of what’s called The Apostolic Age. The greatest of them was Irenæus. Though he wasn’t a direct student of the Apostle, he was influenced by Polycarp, & is considered by many as one of the premier and first Church Fathers.Not much is known of Irenæus’ origins. From what we can piece together from his writings, he was most likely born and raised in Smyrna around AD 120. He was instructed by Smyrna’s lead pastor, Polycarp, a student of John. He says he was also directly influenced by other pupils of the Apostles, though he doesn’t name them. Polycarp had the biggest impact on him, as evidenced by his comment, “What I heard from him, I didn’t write on parchment, but on my heart. By God’s grace, I bring it constantly to mind.” It’s possible Irenæus accompanied Polycarp when he traveled to Rome and engaged Bishop Anicetus in the Easter controversy we talked about last episode.At some point while still a young man, Irenæus went to Southern Gaul as a missionary. He settled at Lugdunum where he became an elder in the church there. Lugdunum eventually became the town of Lyon, France. In 177, during the reign of Marcus Aurelius, the church in Lugdunum was hammered by fierce persecution. But Irenæus had been sent on a mission to Rome to deal with the Montanist controversy. While away, the church’s elderly pastor Pothinus, was martyred. By the time he returned in 178 the persecution had spent itself and he was appointed as the new pastor.Irenæus worked tirelessly to mend the holes persecution had punched in the church in Southern Gaul. In both teaching and writing, he provided resources other church leaders could use in faithfully discharging their pastoral duties, as well as refuting the various and sundry errors challenging the new Faith. During his term as the pastor of the church at Lyon, he was able to see a majority of the population of the City converted to Christ. Dozens of missionaries were sent out to plant churches across Gaul.Then, about 190, Irenæus simply disappears with no clear account of his death. A 5th C tradition says he died a martyr in 202 in the persecution under Septimus Severus. The problem with that is that several church fathers like Eusebius, Hippolytus, & Tertullian uncharacteristically fail to mention Irenæus’ martyrdom. Because martyrs achieved hero status, if Irenæus had been martyred, the Church would have marked it. SO most likely, he died of natural causes. However he died, he was buried under the altar St. John’s in Lyons.Irenæus’ influence far surpassed the importance of his location. The bishopric of Lyon was not considered an important seat. But Irenæus’ impact on the Faith was outsized to his position. His keen intellect united a Greek education with astute philosophical analysis, and a sharp understanding of the Scriptures to produce a remarkable defense of The Gospel. That was badly needed at the time due to the inroads being forged by a new threat – Gnosticism, which we spent time describing in Season 1.Irenæus’ articulation of the Faith brought about a unanimity that united the East & Western branches of the Church that had been diverging. They’d end up reverting to that divergence later, but Irenæus managed to bring about a temporary peace through his clear defense of the faith against the Gnostics.Irenæus admits he had a difficult time mastering the Celtic dialect spoken by the people where he served but his capacity in Greek, in which he composed his writings, was both elegant & eloquent without running to the merely flowery. His content shows he was familiar with the classics by authors like Homer, Hesiod, & Sophocles as well as philosophers like Pythagoras & Plato.He shows a like familiarity with earlier Christian writers such as Clement, Justin Martyr, & Tatian. But Irenæus is really only 1 generation away from Jesus and the original Apostles due to a couple long life-times; that of John, and then his pupil, Polycarp. We find their influence in Irenæus’ remark impugning the appeal of Gnosticism, “The true way to God, is through love. Better to know nothing but the crucified Christ, than fall into the impiety of overly curious inquires & silly nuances.” Reading Irenæus’ work on the core doctrines of the Faith reveal his wholehearted embrace of Pauline theology of the NT. Where Irenæus goes beyond John & Paul was in his handling of ecclesiology; that is, matters of the Church. Irenæus wrote on things like the proper handling of the sacraments, and how authority in the church ought to be passed on. A close reading of the 2nd C church fathers reveals that this issue was of major concern to them. It makes sense it would. Jesus had commissioned the Apostles to carry on His mission and to lay the foundation of the Faith & Church. The Apostles had done that, but in the 2nd C, the men the Apostles had raised up were themselves aging out. Church leaders were burdened with the question of how to properly pass on the Faith once for all delivered to the saints, to those who came next. What was the plan?We’ll come back to that later . . .Irenæus was a staunch advocate of what we’ll call Biblical theology, as opposed to a theology derived from philosophical musing, propped up by random Bible verses. He’s the first of the church fathers to make liberal use of BOTH the Old & New Testaments in his writings. He uses all four Gospels and nearly all the letters of the NT in the development of his theology.His goal in it all was to establish unity among believers. He was so zealous for it because of the rising popularity of Gnosticism, a new religious fascination attractive an increasing number of Christians.Historians have come to understand that like many emergent faiths, Gnosticism was itself fractured into different flavors. The brand Irenæus dealt with was the one most popular in his region; Valentinian Gnosticism, or, Valentinianism.While several writings are attributed to Irenæus, by far his most important and famous was Against Heresies, his refutation of Gnosticism. Written sometime btwn 177 & 190, it’s 5 volumes is considered by most to be the premier theological work of the ante-Nicene era. It’s also the main source of knowledge for historians on Gnosticism and Christian doctrine in the Apostolic Age. It was composed in response to a request by a friend wanting a brief on how to deal with the errors of both Valentinus & Marcion. Both had taught in Rome 30 yrs earlier. Their ideas then spread to France.The 1st of the 5 volumes is a dissection of what Valentinianism taught, and more generally how it differed from other sects of Gnosticism. It shows that Irenæus had a remarkable grasp of a belief system he utterly & categorically rejected.The 2nd book reviewed the internal inconsistencies and contradictions of Gnosticism.The last 3 volumes give a systematic refutation of Gnosticism from Scripture & tradition which Irenæus makes clear at that time were one and the same. He shows that the Gospel which was at first only oral, was subsequently committed to writing, then was faithfully taught in churches through a succession of pastors & elders. So, Irenæus says, The Apostolic Faith & tradition is embodied in Scripture, and in the right interpretation of those scriptures by pastors (AKA as bishops). And the Church ought to have confidence in those pastors’ interpretations of God’s Word because they’ve attained their office through a demonstrated succession. Of course, the succession Irenæus referred to was manifestly evident by virtue of the fact he wrote in the last quarter of the 2nd C & was himself, as we’ve seen, just a generation removed from the Apostle John.Irenæus set all this over against the contradictory opinions of heretics who fundamentally deviated from this well-established Faith & simply could not be included in the catholic, that is universally agreed on, faith carved out by Scripture and its orthodox interpretation by a properly sanctioned teaching office.The 5th and final volume of Against Heresies includes Irenæus’ exposition of pre-millennial eschatology; that is, the study of Last things, or in modern parlance – the End Times. No doubt he does so because it stood in stark contrast with the muddled teaching of the Gnostics on this subject. It might be noted that Irenæus’ pre-millennialism wasn’t unique. He stood squarely with the other writers of the Apostolic & post-apostolic age.Irenæus’ view of the inspiration of Scripture is early anticipation of what came to be called Verbal plenary inspiration. That is, both the writings and authors of Scripture were inspired, so that what God wanted expressed was, without turning the writers into automatons. God expressed His will through the varying personalities of the original authors. He even accounts for the variations in Paul’s style across his epistles to his, at times, rapid-fire dictation & the agency of the Holy Spirit’s urging at different times and in different situations.Irenæus’ emphasis on both Scripture and the apostolic tradition of its interpretation has been seen as a boon to the idea of establishing an official teaching magisterium in the Church. Added to that is his remarks that the church at Rome held a special place in providing leadership for the Church as a whole. He based this on Rome being the location of the martyrdom of both Peter & Paul. While Irenæus acknowledges they did not START the church there, he reasoned they most certainly were regarded as its leaders when they were there. And there was a tradition that Peter appointed the next bishop, one Linus, to lead the Church when he was executed. While it’s true Irenæus did indeed suggest Rome ought to take the lead, he said it was the CHURCH there that ought to do so; not its bishop. The point may seem minor, but it’s important to note that Irenaeus himself resisted positions taken by the Bishop at Rome. In our last episode, we noted his chronicle of Polycarp’s & Anicetus’ disagreement over when to celebrated Easter. Anicetus’ successor was Bishop Victor, who took a hardline approach with the Quartodecamins and wanted to forcefully punish them. While as the bishop of the church in Lyon, Irenaeus was ready to follow the policy of the Church at Rome, he objected to Victor’s heavy-handedness and reminded him of his predecessor’s more fair-minded policy.So while Irenaeus does indeed urge a role of first-place for the Church at Rome, we can’t go so far as to say he establishes the principle of the primacy of the bishop of Rome. He’s not an apologist for papal primacy.Nor does he advocate apostolic succession as it’s come to be defined today. What Irenaeus does say is that the Scriptures have to be interpreted rightly; meaning, they have to align with that which the Apostles consistently taught, and that the people who were to be trusted to that end were those linked back to the Apostles because they’d HEARD them explain themselves.He argued this because the Gnostics claimed a secret oral tradition given them from Jesus himself. Irenaeus maintained that the pastors & elders of the Church were well-known and linked to the Apostles and had always maintained the same message that wasn’t secret at all. Therefore, it was those pastors who provided the only safe interpretation of Scripture.For Irenaeus, apostolic authority was only valid so long as it actually squared with apostolic teaching, which itself was codified in the Gospels and epistles of the NT – along with what the direct students of the Apostles said they’d taught. Irenæus didn’t concoct a formula for the passing of apostolic authority from one generation to the next in perpetuity.Irenaeus became a treasured authority for men like Hippolytus and Tertullian who drew freely from him. He also became a major source for establishing the canon of the NT. He regarded the entire OT as God’s Word as well as most of the books our NT while excluding a large number of Gnostic pretenders. There’s some evidence that before Irenaeus, believers lined up under different Gospels as their preferred accounts of the Life of Jesus. The Churches of Asia Minor preferred the Gospel of John while Matthew was the most popular overall. Irenaeus made a convincing case that all 4 Gospels were God’s Word. That made him the earliest witness to the canonicity of M,M,L & J. This stood over against the accepted writings of a heretic named Marcion who only accepted portions of Luke’s Gospel.Irenaeus cited passages of the NT about a thousand times, from 21 of the 27 books, including Revelation. Inferences to the other books can be found as well.Irenaeus provides a perfect bridge from the Apostles to the next phase of Church History presided over by the Fathers, of which he’s considered among the first.

Feb 26, 2017 • 0sec

The First Centuries – Part 04 / An Easter Tussle

Have you noticed that, generally-speaking, Christians like to argue?Maybe we get it from our spiritual ancestors, the Jews. Once while on a tour of Jerusalem at what are called the Southern Steps of the Temple Mount, our Jewish guide told us that a frequent joke among his people was that where there are 2 Jews, there’s 3 opinions.Yeah; it seems controversy has been a part of the history of The Church since its inception. And maybe that’s really more a “human” tendency than something unique to, or the sole prerogative of the followers of Jesus. (more…)

Feb 12, 2017 • 0sec

The First Centuries Part 03

In part 1 we took a look at some of the sociological reason for persecution of Christians in the Roman Empire. Then last time we began a narrative-chronology of the waves of persecution and ended with Antonius Pious.A new approach in dealing with Christians was adopted by Marcus Aurelius who reigned form 161–180. Aurelius is known as a philosopher emperor. He authored a volume on Stoic philosophy titled Meditations. It was really more a series of notes to himself, but it became something of a classic of ancient literature. Aurelius bore not a shred of sympathy for the idea of life after death & detested as intellectually inferior anyone who carried a hope in immortality. (more…)

Feb 5, 2017 • 0sec

The First Centuries – Part 02

This is part 2 in our follow-up series on the first centuries in Church History. We’re concentrating on the persecution Jesus’ followers endured. In part 1, we examined the social & civic reasons for persecution in the Roman Empire.The suspicion of nefarious intent by Christians, fueled by their withdrawal from society due to its tacit connection to paganism, morphed into a suspicion of covert actions Jesus’ followers were taking to subvert society. Why were Christians so secretive if they weren’t in fact doing something wrong? And if the rumors were true, Christians WERE doing odd things; like pretending slaves had the same dignity as freemen; that women and children were to be honored as equal to men; and they rescued exposed infants. Why, if they kept all that up, and more joined their cause, what was to become of the world? It would look very different from the one that had been. (more…)

Jan 29, 2017 • 0sec

The First Centuries – Part 01

Welcome BACK to Communion Sanctorum: History of the Christian Church.We ended our summary & overview narrative of Church History after 150 episodes; took a few months break, and are back to it again with more episodes which aim to fill in the massive gaps we left before.This time, we’ll do series that go into detail on specific moments, movements, people, places, and other topics. (more…)

Sep 4, 2016 • 0sec

140-The End

The final episode of Communio Sanctorum. We look briefly at the reaction of some Protestants to Manifest Destiny. DL Moody, The Holiness Movement, Phoebe Palmer, The Azusa Street Revival.This 150th episode of CS is titled The End.150 episodes! And this is the rebooted v2. We had a hundred episodes in v1 before I started over again in an attempt to clean up the timeline and fill in some gaps. (more…)

Aug 28, 2016 • 0sec

139-Evangementalism

This 139th episode is titled Evangementalism,We’ve spent a couple of episodes laying out the genesis of Theological Liberalism, and concluded the last episode with a brief look at the conservative reaction to it in what’s been called Evangelicalism. Evangelicalism was one of the most important movements of the 20th C. The label comes from that which lies at the center of the movement, devotion to an orthodox and traditional understanding of the Evangel, that is, the Christian Gospel - the Good News of salvation through faith in Jesus Christ.While Evangelicalism is used today mainly to describe the theological movement that came about as a reaction to Protestant theological liberalism, the term can be applied all the way back to the 1st C believers who referred to themselves as “People of the Gospel,” the Evangel. The term was resurrected by Reformers to call themselves “evangelicals” before identifying as Protestants or any of the other labels used for protestant denominations today.The modern flavor of Evangelicalism came about as a merging of European Pietism and revivals among Methodists in England. We might even locate the origin of modern Evangelicalism in the First Great Awakening of the mid-18th C. Its midwives were people like Whitefield, Tennent, Freylinghuysen, and of course Jonathan Edwards.Since major stress of all these was the need for a conversion experience and spiritual new birth, revivalism and an emphasis on the task of evangelism have been front and center in Evangelicalism.As we’ve seen in a past episode, the First Great Awakening was followed a century later by the Second which began in the United States and spread to Europe, then the rest of the world and had a huge impact on how Christians viewed their Faith. What’s remarkable about the Second Great Awakening, is that it came at a time when many church leaders lamented the low state of the Church in Western Civilization. Christianity’s enemies gleefully wrote its obituary. Theological Liberalism helped to push the Faith toward an early grave. But the Second Great Awakening literally shook North American and Europe to their core. A wave of missionaries went out across the globe as a result, spreading the Faith to places no church had existed for hundreds of years, and in some cases, ever before.In newly settled regions on the American frontier, Evangelicalism was carried out in week-long “camp meetings.” Think of a modern concert with multiple bands. Camp meetings were like that, except in place of bands playing music were preachers passionately preaching the Gospel. Might not sound too appealing to our modern sensibilities, but the lonely pioneers of the frontier turned out in large crowds. They’d been too busy building homesteads to consider constructing frontier churches. But now they returned home to do that very thing.One of the largest of these camp meetings took place at Cane Ridge in Kentucky in August 1801. Upwards of 20,000 gathered to listen to Protestant preachers of all stripes.Methodist minister Francis Asbury was just one of several circuit-riders who carried the Gospel all over the frontier. Both Baptists and Methodists worked tirelessly to bring the Gospel to blacks. But the fierce racism of the time refused to integrate congregations. Separate churches were plated for black congregations, of which there were many. In the early 19th C, Richard Allen left the Methodist Church to found the African Methodist Episcopal Church. In the US, it wasn’t long before Evangelical Baptists and Methodists outnumbered older denominations of Episcopalians and Presbyterians, groups where theological liberalism had infiltrated.Charles Finney was an attorney-turned-revivalist who transferred the excitement and energy of the rural camp-meetings to the urban centers of the American Northeast. An innovator, Finney encouraged the newly converted to share the story of how they came to the Faith – called ‘giving your testimony.’ He set what he called an “anxious bench” near the front of rooms where he spoke as a place where those who wanted prayer or to make a profession of faith in Christ could sit. That eventually turned into the modern ‘altar call’ that’s a standard fixture of many Evangelical churches today.By the start of the American Civil War in the mid-19th C, Evangelicalism was the predominant religious position of the American people. In an address delivered 1873, Rev. Theodore Woolsey, one-time president of Yale could say, without the least bit of controversy; “The vast majority of people believe in Christ and the Gospel. Christian influences are universal. Our civilization and intellectual culture are built on that foundation.”While there are many brands, flavors, and emphases inside modern Evangelicalism, it’s safe to characterize an Evangelical as someone who holds to several core beliefs: those being à1) The authority and sufficiency of Scripture2) The uniqueness of salvation through the cross of Jesus Christ,3) The need for personal conversion4) And the urgency of evangelismFurther refining of Evangelicalism took place when there was a debate over the first of its core doctrines – the authority and sufficiency of Scripture. This is where Fundamentalism diverged from Evangelicalism. The other three core distinctives of Evangelicalism all rest on the authority and sufficiently of the Bible. And while Evangelicalism began as a reaction to theological liberalism, some of the ideas of that liberalism crept into some Evangelical’s view of Scripture.You see, it’s one thing to say Scripture is authoritative and sufficient and another to then say the entire Bible is Scripture. Is the Bible God’s Word, or does it just contain God’s Word? Do we need scholars and those properly educated to tell us what is in fact Scripture and what’s filler? Are the actual WORDS God’s Words, or do the words need to be taken together collectively so that it’s not the words but the meaning they convey that makes for God’s authoritative message?Some Evangelical leaders noticed their peers were moving to a position that said the Bible wasn’t so much God’s Word as it contained God’s Message. While they weren’t as extreme as the Liberal Theologians, they effectively ended up in the same place. This debate goes on in the Evangelical church today and continues to be the source of much unrest.Conservative Evangelicals started linking the authority of Scripture to the doctrine of inerrancy; that is, belief the Bible’s original writings contained no errors, and that because of the laborious process of transmission of the texts over time, while we can’t say our modern translations are perfect or without any error, they are virtually inerrant; they are trustworthy versions of the originals.At the dawn of the 20th C, Princeton Theological Seminary became the epicenter of this debate as a leading defender of the authority of the Bible. It had long been an advocate for the infallibility of Scripture under such luminaries as Archibald Alexander, Charles Hodge, his son, AA Hodge, and BB Warfield. In a seminal essay on the doctrine of Inspiration in the Princeton Review, AA Hodge and BB Warfield defined inspiration as producing the “absolute infallibility” of Scripture. They said the autographs, the original writings of the Bible were free from error, not just in regard to theological matters, but in contradiction to what theological liberalism claimed, they were without error in regard to ALL their assertions, including those touching science and history.The theological liberalism coming from Europe had a mixed reception in the US at the outset of the 20th C. At first, most churches remained conservative and blissfully unaware of the slow sea-change taking place in the intellectual centers of American universities and seminaries. Battle lines were drawn between liberals and conservatives who were branded with a new label = Fundamentalists. The battle they carried out in the hallowed halls of academia soon spilled over into the pews. It was referred to as the contest between modernists and fundamentalists.While modernists embraced a host of varying ideologies, they shared two presuppositions.First, they urged, Christianity must be reframed in light of new insights; meaning the tenants of Protestant Liberalism.Second, the Faith had to be liberated from the cultural encrustations of traditionalism that had obscured the REAL MEANING of the Bible. What that effectively meant was that ALL and ANY traditional beliefs about what the Bible said was no longer valid. It was a knee-jerk rejection of conservatism.Though the term Fundamentalism wasn’t coined until 1920, it flowed from the 1910 publication The Fundamentals. It was a synthesis of different conservative Protestants who united to battle the Modernists who seemed to be taking over Evangelicalism. Fundamentalists banded together to launch a counteroffensive.There were 2 streams of the early Fundamentalist movement.One was intellectual fundamentalism led by J. Gresham Machen [Gres’am May-chen] and his Calvinist peers at Princeton. [the ‘h’ in Gresham is silent!]The other was populist fundamentalism led by CI Schofield who produced the best-selling Scofield Reference Bible which contained his expansive notes and laid out a dispensationalism many found appealing.Other notable fundamentalist leaders were RA Torrey, DL Moody, Billy Sunday, and the Holiness Movement that moved in several denominations, most notably the Nazarenes.While the intellectual and populist streams of fundamentalism attempted to unite in their opposition to modernism, there were simply too many doctrinal differences between all the various groups inside the movement to allow for a concerted strategy in dealing with Liberalism. As a result, Modernists were able to continue their infiltration and take-over of the intellectual centers of the Faith.In reaction to modernists, in 1910, a group of conservative Presbyterians responded with five convictions that came to be considered the core Fundamentals from which the movement derived its name. Those five convictions flowed from their certainty in the inerrancy and infallibility of Scripture. They were . . .1) The inerrancy of the original writings.2) The virgin birth of Jesus.3) The substitutionary atonement of Jesus on the cross.4) His literal, bodily resurrection.5) A belief that Jesus’ miracles were to be understood as real events and not merely literary mythology meant to teach some ethical imperative. Jesus really fed thousands with a few fish and loaves, really raised Jairus’ daughter from the dead, and really walked on water.These fundamentals were elaborated and released between 1910 and 15 in a set of booklets called The Fundamentals: A Testimony to the Truth. The Stewart brothers funded their publication and ensured they were distributed to every Christian leader across the US. Some three million copies were circulated before WWI to combat the threat of Modernism.