80,000 Hours Podcast

Rob, Luisa, and the 80000 Hours team

Unusually in-depth conversations about the world's most pressing problems and what you can do to solve them.

Subscribe by searching for '80000 Hours' wherever you get podcasts.

Hosted by Rob Wiblin and Luisa Rodriguez.

Subscribe by searching for '80000 Hours' wherever you get podcasts.

Hosted by Rob Wiblin and Luisa Rodriguez.

Episodes

Mentioned books

Dec 31, 2019 • 1h 53min

#17 Classic episode - Will MacAskill on moral uncertainty, utilitarianism & how to avoid being a moral monster

Join Will MacAskill, an Oxford Philosophy Professor and co-founder of the effective altruism movement, as he navigates moral uncertainty and the challenges of utilitarianism. He argues that just as past societies upheld shocking norms, we too may be making grave moral errors today. MacAskill discusses the need for a 'long reflection' to overcome these biases and advocates for a moral framework that pushes beyond common sense. The conversation also explores ethical decision-making, the intricacies of personal identity, and rethinking societal norms.

Dec 16, 2019 • 4h 42min

#67 – David Chalmers on the nature and ethics of consciousness

David Chalmers, a leading philosopher on consciousness, and Arden Koehler, an ethics PhD student, explore the nature of conscious experience. Chalmers introduces the mind-bending concept of 'philosophical zombies' to question moral status. They discuss the trolley problem involving conscious humans and non-conscious zombies, sparking a debate over what qualifies beings for moral consideration. The duo also dives into the ethics of AI consciousness and the implications of virtual reality, challenging listeners to rethink reality, ethics, and our responsibilities towards all forms of consciousness.

Dec 5, 2019 • 2h 1min

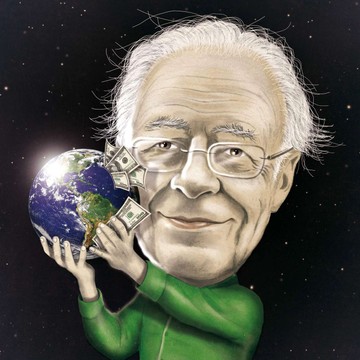

#66 – Peter Singer on being provocative, effective altruism, & how his moral views have changed

In a thought-provoking discussion, Peter Singer, a renowned professor of bioethics at Princeton University, addresses controversial topics from his early days in moral philosophy to present dilemmas. He reflects on how provoking discussion can amplify awareness of critical issues like global poverty and animal ethics. Singer shares insights on the effective altruism movement, the balance between personal beliefs and large-scale impact, and the complexities of advocating for unpopular opinions. His evolving moral views challenge listeners to think deeply about their ethical decisions.

Nov 19, 2019 • 1h 41min

#65 – Ambassador Bonnie Jenkins on 8 years pursuing WMD arms control, & diversity in diplomacy

Ambassador Bonnie Jenkins, a former U.S. State Department official and founder of WCAPS, shares her remarkable journey in diplomacy. She discusses her role in global arms control, emphasizing the critical need for diversity in the field. Jenkins highlights the complex relationship between global health security and nuclear threat reduction, and the unique challenges posed by biological weapons. She advocates for increased collaboration across sectors to tackle pressing global threats, while also reflecting on the moral dilemmas faced by civil servants in their roles.

40 snips

Oct 25, 2019 • 2h 11min

#64 – Bruce Schneier on how insecure electronic voting could break the United States — and surveillance without tyranny

In this enlightening discussion, Bruce Schneier, a world-renowned computer security expert from Harvard Law, tackles the grave risks of electronic voting systems. He warns that a successful hacking attempt could lead to widespread electoral chaos, eroding public trust in democracy. The conversation also delves into the complexities of digital platforms manipulating information, the implications of cybersecurity vulnerabilities, and the tension between security and surveillance practices. Schneier calls for transparency and enhanced protections to secure our digital future.

Sep 25, 2019 • 3h 15min

Rob Wiblin on plastic straws, nicotine, doping, & whether changing the long-term is really possible

In a captivating discussion, David Kadavy, host of "Love Your Work," and Jeremiah Johnson, from the "Neoliberal Podcast," explore intriguing topics with Rob Wiblin. They dive into the role of nicotine in enhancing focus and the misconception about plastic straws in environmental debates. The conversation also touches on the ethics of performance-enhancing drugs in sports, the challenges of information overload, and the moral responsibilities we hold toward future generations. Get ready for a thought-provoking blend of personal insights and global perspectives!

Sep 16, 2019 • 4min

Have we helped you have a bigger social impact? Our annual survey, plus other ways we can help you.

Discover how an annual survey aims to evaluate the impact of resources on listeners' social contributions. The discussion emphasizes the importance of audience feedback in improving services like the job board, articles, and career advising. Learn how filling out this survey can help shape future initiatives and ensure the podcast is continually enhancing its value. Plus, explore ways to stay connected through newsletters and social media for updates on new resources and insights.

8 snips

Sep 3, 2019 • 3h 18min

#63 – Vitalik Buterin on better ways to fund public goods, blockchain's failures, & effective giving

Vitalik Buterin, lead developer of Ethereum and a pioneer in cryptoeconomics, discusses the significant flaws of current blockchain technologies, calling them often ineffective. He explores innovative funding models for public goods, like quadratic voting and decentralized autonomous organizations (DAOs). Buterin critiques common myths in crypto and emphasizes the importance of effective altruism within the community. He also highlights the potential of blockchain for enhancing collaboration and solving global challenges, advocating for a broader vision beyond mere currency.

Aug 5, 2019 • 2h 12min

#62 – Paul Christiano on messaging the future, increasing compute, & how CO2 impacts your brain

Paul Christiano, a machine learning researcher at OpenAI, dives into thought-provoking concepts about our future and AI's role in it. He discusses the idea of messaging our distant descendants or future intelligent beings to help them avoid humanity’s past mistakes. The conversation touches on the implications of CO2 levels on cognitive function and the urgent need for improved ventilation. Christiano also explores the evolving landscape of AI safety and the delicate balance required in AI development to ensure alignment with human values.

Jul 17, 2019 • 1h 55min

#61 - Helen Toner on emerging technology, national security, and China

Helen Toner, Director of Strategy at Georgetown University's CSET, dives into the intersection of artificial intelligence and national security. She draws parallels between AI's potential impact and the transformation brought by electricity. Toner discusses the complexities of U.S.-China relations regarding AI, emphasizing the balance needed between innovation and security. She also explores the implications of data in governance and the importance of informed policymaking, highlighting her unique experiences and insights into this rapidly evolving field.