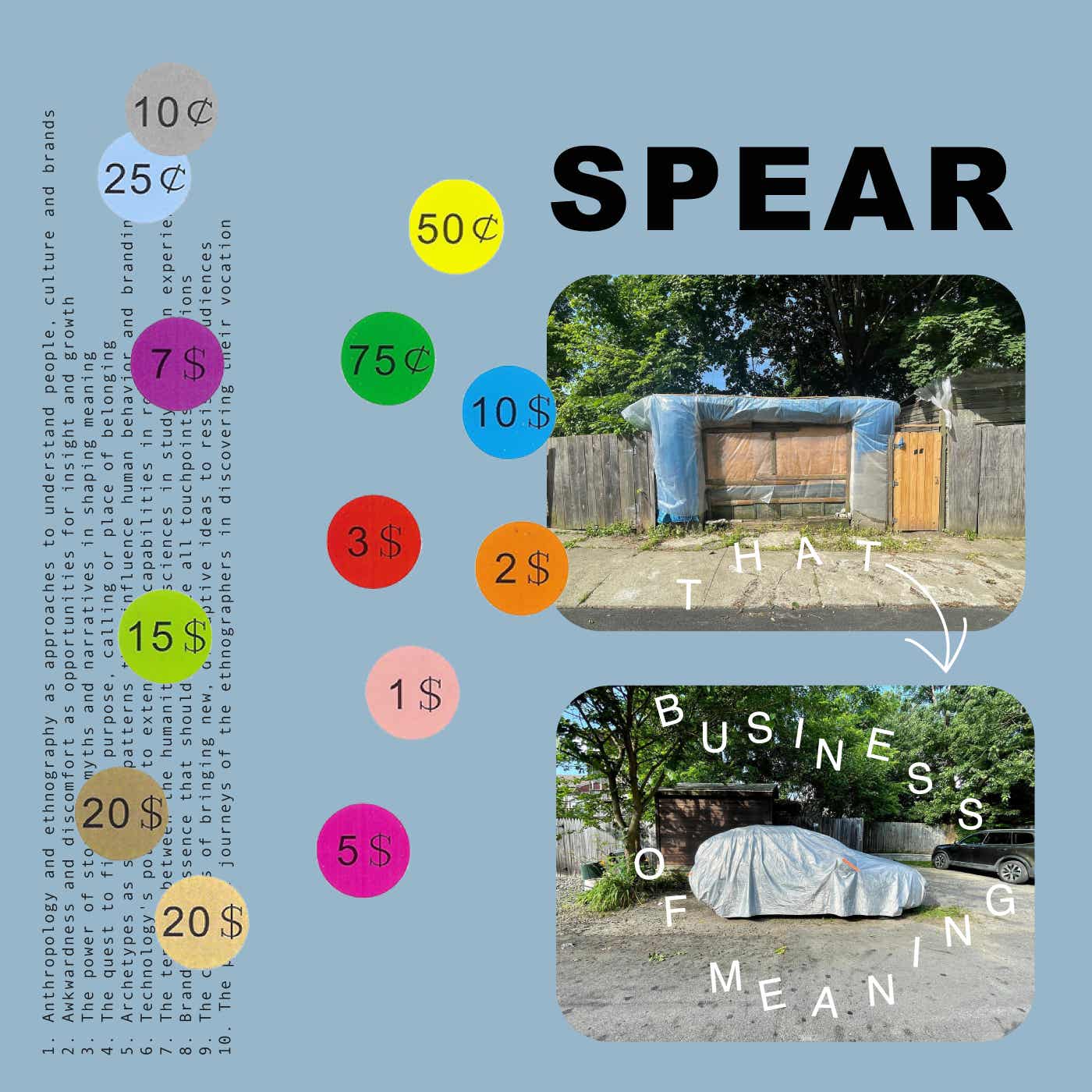

THAT BUSINESS OF MEANING Podcast

Peter Spear

A weekly conversation between Peter Spear and people he finds fascinating working in and with THAT BUSINESS OF MEANING thatbusinessofmeaning.substack.com

Episodes

Mentioned books

Sep 16, 2024 • 49min

Max Kabat on Community & Brand

Max Kabat is the co-founder of goodDog, a brand consultancy. I first met Max and his partner Lisa Hyman way back in 2013, when they first hired me to partner on brand discovery for their client, Leesa Sleep. Since then, we have partnered many, many times, and I was excited to hear more about him, Marfa and his story. Max is also the publisher of the West Texas newspaper The Big Bend Sentinel and owner of The Sentinel, a community gathering space in Marfa, Texas. Max, very good to see you. Thank you so much for agreeing to be a part of this.Yeah, happy to be a part of this, Peter. Always nice chatting with you, my friend.Nice. So I start all these conversations in the same way, with the question that I borrowed slash stole from a neighbor here in Hudson. She teaches oral history. Her name is Suzanne Snyder. And I love the question so much, but it's so beautiful, I kind of overexplain it. I caveat it up front. So before I ask, I want you to know that you're in total control. You can answer or not answer any way that you want to. And the question is, where do you come from?Yeah, I come from New York. I'm a New Yorker. I spent the first 30 something years of my life, mostly in the Northeast. I went to college in rural Pennsylvania. And yeah, that was where I sort of was born and bred and raised. And then I married, I met a cattle rancher's daughter from South Texas. And I moved to Texas in 2016, about eight years ago.And you're from New York. So where did you grow up? Where were you?Yeah, my parents are products of immigration of some sort. And they were both born and raised in and around New York City. I was born in New York City, in Manhattan, and then my parents moved up the Hudson River to Briarcliff Ossining when I was a two-year-old kid, and that's where I was sort of raised.Yeah. And what do you have memories of, as a kid, what you wanted to be when you grew up?Oh, I don't know, probably any kid during that era, I probably wanted to be a professional athlete. I think that all died quite quickly. I am athletic, but I am not very large and not very strong. And so yeah, that probably died pretty quickly.Yeah. And what was life? What was it like growing up? And what do you say Briarcliff Ossining? Is that one of those adjacent?Those are two towns. Yeah. But some people don't know Briarcliff Manor. It's now probably most known because Donald Trump bought the rinky-dinky golf course that was there and turned it into Trump National, probably in the last 20 plus years. Or it's also in Mad Men.Oh, wow.Oh, yeah. The main character, I can't remember his name at the moment travels up the Hudson. Don Draper goes to Briarcliff. That's where he lives. He commutes up to.Oh, wow. What was it like growing up there? What was your.Yeah. Suburban, you know, New York City, growing up this Westchester County, all the other, I think, counties that surround New York City in the Tri-State area. You know, people commute. A lot of people commute. A lot of people are involved in business and supporting business and all those kinds of things. And my parents didn't commute. They worked locally. But yeah, that was sort of the town I grew up in.Yeah. Did you have a relationship with New York City? Did you identify as a New York? 100 percent. Yeah, 100 percent. I always said New York if I was in and around somewhere else, if somebody asked me where I was from, I would sort of start pointing towards the place, you know, and then or I was it's funny, I was growing up as a kid or even as a young adult living in New York City after college, I always took offense. Oh, you're from upstate. No, no, no, no. I'm not from upstate. Whereas now I live in literally in one of the most desolate places in the country. And, you know, rural America has a very soft spot in my heart. And I probably should have worn that more proudly as sure, I am from upstate technically north of the city would be up.Yeah. Tell me about where you are now. I'm in Marfa, Texas. It's in Big Bend country, the Big Bend region of far west Texas. I'm on the border. My closest city is El Paso, about 180 miles away. Or I live right in the middle of town. It's about 60 miles from the county that I'm in Presidio County borders as a port city. Ojinaga is the Mexico side. And Presidio is the U.S. side. And we're in a set of grasslands between two mountain ranges. Bottom of the Rockies. If you look at a map, the bottom of Rockies sort of spills out and goes actually all the way into Mexico. But we're at the bottom of the Rockies. So we're nine-tenths of a mile high in the high desert.Yeah. And how do you describe Marfa to somebody who's not encountered it?I think it's sort of an anomaly of a place. It's an island in the middle of the desert, as people call it. It's really hard to get to. It takes intestinal fortitude. It takes effort to get here, not just to live here. It takes an effort to get here. And so it's sort of a self-selecting kind of idea. And yeah, people. It's had a lot of change over the last bunch of years, the last hundred years, we should call it. You know, there were World War bases that were out here. There were POW camps. This was the film Giant. Have you ever seen Giant was filmed out here. So this was sort of that at one point in time, even before that, it was Mexico? Was it the U.S.? Some people sort of made a border. And lo and behold, this was on the U.S. side. So, you know, it's part of the Chihuahuan Desert. The Chihuahuan Desert reaches starts in the state of Chihuahua, a little bit south of that in Mexico and comes up through West Texas, a little bit into Mexico, a little bit into Arizona. So what is it? It's a place. It's an ecosystem. It has a border, but it doesn't. It was really great grazing and cattle country. And until it wasn't until it was overgrazed, it was the far reaches of desolation. It's known for really high-end art and sort of the father of minimalist art, Donald Judd came here in the 70s and sort of established himself and established the place. And so it's a lot of different things. An enigma, I don't know, might be a one-word answer, but a complicated but easy way to sort of explain that it's everything and nothing all at the same time.Yeah. What do you think people get wrong about Marfa? There's an idea of what Marfa is, but people haven't really experienced it or known. But what do people not understand or get about it?I think that it's interesting the last number of years, if anything changed in the pandemic, I think all the quote-unquote special places sort of got a lot more attention in the pandemic, especially if they were not in the middle of a city. People started exploring what it might look like to live somewhere else. And those places, everything drastically changed. I think it was sort of a lot of things went into turbo into overdrive. But. I'm sorry, your question again was I lost my train of thought.What do people get wrong about Marfa?There's probably an impression. Yeah, sorry. I remember where I was going with this. Thank you. I think people get wrong at everything about a place that they have expectations about what it's supposed to be. And they go in with these preconceived notions instead of just experiencing. And I think it's. That's what I would sort of hope people would be able to do as a visitor of a place, sort of experience what it is, take it for what it's worth. You know, if you go in with certain expectations, I think that sort of clouds your judgment. Not to say that that's not who we are as humans. We at our core. But when you go to a place and you have a preconceived notion of what it's supposed to be and the way it's supposed to be, you're probably stuck in a situation where it's not going to meet or maybe exceeds or. But I think it just sort of clouds the whole experience.So I of course, we met through your work at Good Dog as a co-founder, brand strategy and growth strategy. You also have you're the publisher of the Big Bend Sentinel and the owner of the Cisco, which is a gathering space. How did let's start with the with Good Dog. How did you get into brand that kind of brand strategy work? When did you first sort of encounter the idea of brand and that you could make a living doing that kind of work?Yeah. I had spent some time after college to go back to your early question. What did I want to be when I was brought up? I won't be an athlete. I really wanted to be in sports marketing. And that's what I thought I was going to do after college. And then two guys I used to caddy for in the summers offered me a job to go work on Wall Street. So my first three years on were working on Wall Street at a broker-dealer firm and then at a hedge fund that was a client of the broker-dealer in trading equities, options, swaps, that kind of stuff. I didn't get an MBA, but I like to say that that sort of gave me an understanding of the way in which the business world works through a particular lens. But it just gave me a sort of a good understanding about business. I didn't like where that was leading or what that was, what my life was like there. And I ended up spending a bunch of years at a media company that sold space, sold media to advertisers. They had an outdoor advertising business and a sports marketing signage and sponsorship business. And it was sort of there, I like to say, that my education of the United States was I was spending a lot of time trying to ingratiate myself into the NASCAR community and sort of traveled around the country, not the coasts, the middle of the country and sort of realized very quickly that, oh, I am not from America. I might think that New York City is the center of the world and I might have all these ideas and ideals. But there's this whole other place called America that I don't know a lot about. And it made me sort of start to question a lot.It was also after the 2008 crash, I was in college in 2001. So I think I was sort of already into this mindset of sort of questioning and thinking and realizing that we're, you know, the experience is short and we're all intertwined. And how do you leave the place better than when you started? And I realized that I think, you know, through that media sales, the company was called Van Wagner. I realized that marketing had this awesome ability and advertising, this awesome ability to influence people and affect change. I was just sort of a cog in the wheel. I was part of the system. What happens if I could use the system to sort of do something different to start to sort of shift consciousness to a more conscious place? So that didn't work there at that media company. I had tried to rally support from senior leadership to say, hey, what would happen if I could do this, but stay here? And they weren't really into that. So I ended up going to work for an integrated marketing agency where I met Lisa, my business partner, good dog. She was my boss. And she had built this thing that was called Green Dog, Good Dog. It was, you know, sort of using integrated marketing's ability to influence people and affect change, but do it for good, for good brands and all these sort of this is 15 years ago, let's say. So, you know, one of the only ways in which you could vote with your dollar was to do it via food and beverage. That was sort of the closest tie to there's a you can eat organic, you can farm a certain way, you can support a certain kind of lifestyle. And it's also healthy for it's, you know, it's good for you and good for the planet kind of idea. And so those were sort of the first products and services. And so I participated in that rode that wave. And Lisa and I eventually spun out of the larger integrated shop that was like 250 people when we left. And it's and it's a two-person Good Dog is now like a two-person, high-level thinking, high-level doing shop where we work with founder-built brands and mostly in the twenty-five to three hundred million dollar run rate work through growth plateaus as they scale.Yeah. Can you tell I love can you tell me a story about that moment where you encountered America, as you said, at the NASCAR? You know, I'm I don't I think you said you're you won't be able to see me, but I'm a if you're from New York, I'm a curly-haired New York Jew. That's what I look like. Right. And so I talked a different way. I looked a little bit different. I acted a little bit different. I dressed a little bit different. And here I was trying to figure out how to get on the inside of a community that I didn't know a ton about. I didn't grow up watching NASCAR, but I quickly realized that the fandom was incredibly palpable and super powerful and brands were spending oodles of dollars to try to ingratiate themselves into that community and at the same time sort of create these kinds of experiences. And those were things that the company I worked at was really good at. And also, yeah, I just was trying to figure out where was there a place for me in business? And I did it for a bunch of years and became a part of sort of the business community in some sense. I would travel from race to race. I would hang out in the pits. I met some really fantastic people. It was a really amazing experience. And, you know, there's nothing like standing on the track and feeling the actual weight of cars racing around the track and how it shakes you to your core and wearing headphones. And it's a pretty event. People in the states. It's the whole thing is a spectacle. It's an amazing, amazing experience that travels week after week after week. But yeah, I think that sort of gave me a better idea of, wow, I'm such a pompous idiot, I'm totally not from there's this whole other place called America. I want to learn about this. Yeah, that's how I think I experienced that.What do you love about the work that you do? A good dog. What's the joy in it for you?Yeah, it's a good question. I think that, you know, the joy is I didn't know this at the time, but I guess I always had somewhat of an entrepreneurial spirit, right? Having your own consultancy can be a whole other conversation. Consultancy agency. We're using the word fixer because that's what Lisa and I really do. We're sort of we're brand fixers. But you're an entrepreneur in and of itself, you're running your own business and you're entrepreneurial. But I think until my wife and I sort of started Macy, not Lisa, my business partner, Macy, my wife, when we started this project in Marfa. I think I realized that I always had this want to help people make their idea sort of flourish. And when there's too many people and too many cogs in the wheel and too much distance between the big idea or sort of the heartbeat of the business that's driving it forward and sort of the people that are helping it flourish and they're looked at as more of minions rather than part of a team. I didn't like that whole idea. I sort of wanted to exist in sort of this is a capitalistic society. I was more interested in existing in sort of things that were more tangible and tactile. And you could you felt like you were really your ideas and your influence on helping somebody make their business better was actually making a difference rather than was just sort of part of the system.Yeah. You said that you're calling yourselves fixers. When people ask you about what you do, how do you how are you talking about it? What do you what do you say when people ask you what you do?Yeah. Lisa and I've been at this really long time. And I think that, you know, the thing we've baked a lot of cakes, as I like to say. We've helped people grow their business top line. We've helped them participate in equity events, pre post, raise money, exit a business. We've been at this for a while. And so there's a lot of people, I think the market that exists now from a consultant standpoint, there's a lot of people that are free agents. But what do they actually do? What is their experience? What have they actually built? How have they actually helped somebody sort of grow their business? And so yeah, I think Lisa and I are, we're always helping somebody sort of differentiate themselves. That's what we're helping a business do. And so if you can't differentiate yourself, that's as a consultant, I think that there's an inherent problem there. So everybody is a consultant, everybody's an agency, the barrier to entry to stand up your own thing, takes little effort and some words on a LinkedIn profile, and ta-da, you've hung a new shingle. So we're sort of in this moment of everybody's consultant, everybody's an agency, everybody says they can do something, what can they actually do? We're a fixer. We help you fix your business. We've seen a lot of these situations. And we've been on the inside a ton. And so how do we pull on that experience to help you sort of turn your challenge into a solution?Yeah. I mean, I've had a one sort of angle on your work and seen you get amazing clients. The relationships I think I see you having with them are really strong and very honest and direct. And I was curious about how you get, if there's something about the moments that you engage with clients or the moments they come to you, it seems like you're really alive in these very transitional moments with clients and you really are helping them. And I just wondered how you how you think about the client and how you what those kind of conversations are like when you when a client reaches out to you and they're in a transitional moment. How do you help them understand what's needed to to move forward?Yeah, I think that in transition, thank you for using the word in transition. Those are our favorite opportunities. And that's really when we're at our best. If everything's really great, probably don't call us. There's a lot of really great people that can make really lovely creative that looks a certain way and is creative for creative sake. Or you can have really lovely packaging that doesn't necessarily say anything. But if you're in this moment where you're trying to go from one place to another, where what got you here isn't going to get you to that next stage of growth, if you created a category and the world sort of collapsed around you and you can't remember who you are, what you are and what your special sauce is, if you have a ton of innovation coming out, if you're in transition - those are really big, juicy problems that we love to unpack and help you figure out how to move the business forward. Those are actually the best times to bring you in. You know, that's how we've really gotten to know each other over the last bunch of years. Because a key component of that is, for whom are you for? Really knowing, not just your current consumer, but your growth consumer, and getting to the nitty-gritty. These amazing insights is some of the favorite work that that we get to do with you. That's the best stuff and really helps drive our work forward. And then building a story around that. And then once you sort of have that story, that unique, authentic, culturally relevant, resonant story, that's differentiated for the business built on the insights, then you're able to sort of pull that through. And that last part is obviously super important. And what does that look like from a, you know, if it's a CPG business, what does that look like from a sales and category management story? What does that look like from an innovation story? How does that work? How is your founder story told within the context of this? What's your do you have a thought leadership position or not? What does the creative look like on pack on your, you know, paid or known assets? And, you know, how are you doing business with whom are you doing business with? And so, you know, if you sort of we've, we've, as I said, baked a lot of cakes and pull that through. So that's why we look at Yes, we do that. That very first part, that's sort of our special sauce of you need to, we believe you have to have a really good story, then you have to have a really good plan of how to activate that really good story. And then you have to have, you know, a really, really good creative, a really good way to sort of have that live in the world. And those are the sort of three markers that we believe super strongly about. And that's where we focus our time and effort. Yeah.And I mean, I've, it's, we've, it's been over 10 years, I think, I think 2013 might have been the first the first time that we worked on Lisa sleep. But I remember I had an amazing client who one time I remember I, she always left me, she kind of left me alone, she sort of took my guidance, and she'd had very little feedback very often. And I asked her what that was about, because it was such a pleasure to work with her, you know, and she said, Well, I thought that the first sign of a professional is they let other professionals do their job. And I feel like that's the relationship that we've gotten into where you really do allow me to do my own approach. And I remember the first thing, Lisa, we showed up at the we didn't even interact until the presentation day, in which you guys were presenting your work, and I was presenting my work at the same time. And it was really a beautiful experience. And so I just say that, but I was curious about the role of qual when you're when you're talking to a client, when do you feel like you need qual? And when do you not need qualitative? What's the question for you when you when you want to make that kind of suggestion?Yeah, I mean, a lot of this is sort of arts and science, right. And I think it's really interesting. We're working on a new piece of work, and this business, you know, it's less than $100 million. And they are so they are armed with so much data, and it's such good stuff. But I think that what we're realizing is that they're they're missing a little bit of the softer side of things. And, you know, data definitely tells a story. From a quantitative perspective, it's super helpful. They have a new they have segmentation, they have data back from retail partners, they have data back from their own channels. And we just sort of looked at all this stuff and started talking to this particular client. And, you know, the place that they were hoping to that they want to hang their hat on from a messaging standpoint, we felt could it could be deeper, it could be more intentional. And so that's a really great place for a qual to sort of tie there's, we all have our assumptions, we're all humans, we all go to retreat to our certain corners and have our ideas. But I think that from a qualitative perspective, that sort of insight that you're that you're able to drive in our work, it really helps us. It really helps us drive the whole idea forward. You know, it's great.Yeah, I love that word intentional. When you say that you felt like there's a need to be more intentional on the client side.Yeah, I think, you know, when you're talking about founder-built brands, when you're talking about sort of middle-stage brands, everybody's doing everything. It's all hands on deck all the time, it sort of feels like and, you know, building relationships with CEOs or C level, the C suite and boards, that's that's where a lot of our all of our work sort of starts. I think you need to be super intentional, and they're coming to you for expertise and understanding they know you've, they've done a lot of reps and so have you and so how are you going to sort of make sure that the recommendations that you're providing are intentional? It's not we're not saying, you know, tactical marketing for the sake of tactical marketing, but none of this is everything has to be intentional. We're not talking about Verizon budgets. We're not talking about, you know, everything has to be about ego or it has it has to be about driving the business forward. So everything has to be intentional.Yeah. It also feels like on a number of these experiences I've had, it might be the first time they've really done qual or they've really you've led them into an experience that they haven't really had before. And I'm really curious about that, like what that conversation is like, and how that works.I think that there are a lot of people do quote-unquote brand strategy or messaging or positioning. I don't know what you want to call it. A lot of people are consultants. I think the situations where we find ourselves in sort of the in the dating phase that first sort of feeling each other out, are we going to be right for each other phase is if people want to do the work. If they want to do the hard work about questioning what exists. If they've recognized that everything isn't so rosy. Because nothing is ever rosy. We as humans know that nothing is ever 100% amazing. If they want to lean into that, then they are the kind of person that wants to understand in a different kind of way. They want to make decisions based on something that might feel a little bit intangible to somebody else. That’s why I think our work together has been has been so fruitful for the both of us. Because those people are sort of attracted to us, right? They're attracted to Lisa and myself and our line of thinking and our experience. And so, when we say, hey, we want to learn more about this thing, we're sort of leading the horse to water of they're they're trusting in us. And we're bringing them a solution that we think is going to make the work product better. And yeah, I don't, that's, that's how I think we get there so easily.Yeah, yeah, it's really wonderful. It's wonderful, creates wonderful experiences. I had another question. I wasn't sure how. I have had experience in sort of not for profit space journalist space, which I kind of, I guess I'm laying on top of a B Corp mission-driven kind of culture, like that there's a cultural maybe skepticism about brand marketing, because it's attached to sort of corporate marketing strategy stuff. And I just wondered if that's something that you encounter or no.I think 15 years ago, that was totally the situation. I think, you know, when Lisa and my early work together, you know, one of the biggest pieces of work we worked on when we first started was with the Nature Conservancy, one of the largest, oldest environmental organizations in the world. And we were trying to get them to answer really hard questions. And even then, there was too much bureaucracy. There are too many layers. And they didn't, they didn't want to necessarily do it. They were sort of just like, where's the stuff? Where's the where's the creative? Where's the thing that we're putting into market? And we're like, you are not answering actually the first questions, like, why does somebody give a s**t about nature? Right? You got to answer that question. You can't just make somebody care. Because it's not a good hook. No one, no one is going to give a s**t about if you don't know how to tell somebody or talk to somebody or engage somebody about giving a s**t about nature, why is somebody actually going to care. And so I think all organizations and all that kind of stuff has sort of evolved over the years. But I don't know, I mean, I think I got to a point where in my career, you know, I'm married to a Macy's award-winning photojournalist and documentary filmmaker, her most recent film, Zorowski v Texas just premiered at Telluride a couple weeks ago, to rave reviews. She's really good at what she does. And so when we were living out here in the middle of nowhere, in Marfa, we got to know the folks that owned the paper, it's almost good. It's gonna be 100 years old. And in 2026, they were running it for 30 years, and they wanted to retire. And they sort of asked, they propositioned Macy and I do you want to take it over? You're a marketing brand person, advertising person, and you're a journalist. We've been living out here for a couple years. You know, and we said yes. I think the main reason we said yes, was because I was helping businesses influence people and make change using capitalism and wanted to take that idea and apply it myself. And we also looked at the at the stats, the dew and gloom, the demise of our democracy is contributed by the fact of that local and regional voices are fading with local journalism sort of struggling to find a sustainable business model. And so why am I telling you this story? Because what we did was we sort of leaned into this concept of community, we thought that newspapers have always owned through a macro, through a macro lens, they've always owned this concept of community, but they've just sort of manifested itself through news and information and print and digital. What would happen if we sort of went backwards to go forwards? What would happen if we created a physical space where people could interact and exchange information and participate in capitalism and commerce in the name of getting provided more information? We thought it was ownable because it wasn't, you know, the local newspapers and local journalism writ large is not going to do any good job of fighting the digital fight in comparison to everyone else that doesn't have the capital and the know-how and, but something that we did think we had was sort of leaning into this concept of community. So we did the work, what was, you know, what was the product market fit? What did the community need? And how would we sort of fill that need and sort of thread the needle? And, and for us, it was providing a third space for people that live here and visitors to interact with and serve them coffee and food. And we have a retail shop and it's event space. We do anything from the prom to a hoity-toity wedding that blows through town. And so all of that is to say, we took journalism something that, that I think really struggled to figure out it's over the last 25 years, it's, it's just been a battle and hasn't really done a good job leaning into the concept of brand. And we just, we just owned that idea. We just sort of took unlocked value out of what existed iconography that's been around for, you know, almost a hundred years. It's almost the oldest business in town and in the region. And, and yeah, that was, so to get to your, back to your earlier question, I don't know that everybody has necessarily done it incredibly well, but we happened upon a place that no one was playing, doing the brand play. And we sweat, we, you know, we went headfirst firmly into that and sort of have found a lot of success and a sustainable business model and a better, a better news product by doing so.How are things at the Sentinel? How long has it been now?It's been five years. Yeah. We, we, we opened our doors July 4th, 2019 and published our first newspapers. There's a bilingual paper called El Internacional that's Presidio, the port city, as I said earlier, and the border paper. And yeah, we published our first two papers on July 4th, 2019. Got a really good headstart of nine months before the pandemic hit. But, but yeah, five years later, it's, we've grown top of line revenues, you know, 500%. We have almost, from a couple of people, we've employed 20 people full-time, part-time between the cafe, retail, restaurant, and newspaper. We have more journalism. We're paying people a higher wage in a small town. I know 20 people doesn't sound like a lot, but when your population is less than 2,000, it makes you a decent-sized employer pretty quickly.Yeah. And you used that phrase, third space, right? And I feel like more people are talking about third space all the time now, right? And what have you learned about what that means? You know what I mean?Yeah. Yeah, totally. You know, I think that, I think going back to that, that, that part, I was just saying that, that as the world becomes more digital, it's, it's like, it's a freight train, right? We're not stopping that. And we all participate in it and it's making our lives better. It's making us more connected in some capacity. But I also, I also think maybe this was just a Luddite in me, but I always felt that it was making us more disconnected. And, you know, you look at the rise of experiential marketing over the last X amount of years like that's because creating sort of a physical experience that can be shared somewhat on social a hundred percent, but like creating that physical experience, that's, that's like a memory. That's something that sort of happens in a different kind of world versus the doom scrolling or the, you know, the flash in the pan of reading a something or something that happens online. It's, it's just, it's different. Something I have been thinking about is there's a very large difference in my opinion, between audience and community. And I think we've, we've sort of conflated the two. Community is about a place and its people. Audience is about not, it doesn't have to be sort of place and people specific. And local journalism is about recording the history and telling the stories of a place and its people. If it's, that's, you know, monetize, when you say monetizing audience, you don't talk about monetizing a community. Yes. The Sentinel has done that. We've monetized, you know, figured out a way how to monetize all that stuff. Cause the reality of the situation is news and information is free as, as humans are considered and people don't want to pay for it. And so we're, but people want to pay for experiences and $7 matcha lattes and, you know, all that kind of stuff and being together with people. And so that's sort of, I think that's a big difference for me is that audience is like, you use your users, you're monetizing them. It's, it's, it's not a two-way conversation. It's a one-way conversation. Whereas community is about sort of building and interacting. It's, it's a different kind of thing.Yeah. And I feel like you and I have had exchanges about how that word community has been really, you know, co-opted or, I mean, marketing we're in sort of a community era where brands are building community. You're talking about community. How do you, what are your, how do you think about community in the, in the, in those two worlds that you occupy? You've got people in the brand space probably asking you about community and you're actually building a, be in place.Yeah. I mean, I think I have a very adverse reaction to when people in the brand community are like, it's my community. It's like, No! I'll show you community……We've had such a conversation about digital isn't what it used to be, you know, Facebook, Instagram, all these sort of community aspects. They don't work like they used to. And people are looking for differentiation. People are looking for, you know, a deeper connection. In the last couple of weeks, Columbia, we have some gentlemen from some, some folks over at Columbia that are professors published a paper about, about third space and you know, what building a third space has done for, for places economically and the, the benefits and what that sort of spurns off up from an entrepreneurialist thought, which is really interesting, you know, and then you have brands like I saw Faraday, which is like a men's clothing line. The people that started it, two brothers from the Jersey shore went and took over an old post office and built this third space and are serving coffee and food and home goods and all that kind of stuff, sort of looking for a place to sort of like for people to interact. And I think it's a really interesting place for brands to play. I just wonder, my question that I'm sort of grappling with is like, to what end and like, and for what, right? Like, were this, this business, this idea that we happened into is about, about a place and its people. It's about journalism. It's about providing, you know, some, what some people call a public good for the community and sort of a symbiotic relationship. If you support us, we're going to support you kind of deal. I don't know how it plays out with, with other brands that are like not a coffee shop or not like an actual third space business that are trying to play into it. It feels more pop-uppy and feels not as more like more audience, an idea more about audience rather than community. That isn't to say like the people from Faraday might be like, we want to do something special for the place that we're from. And now we have the capacity and the monetary wealth to do it. Like, I think that's really awesome and great. But I don't know. I'm sort of, I'm trying to figure out like what this moment we're in, what exactly is it?Yeah. So we're kind of near the end of time. What's next for the Sentinel and the other paper?Yeah. So, you know, the first five years have been about building and, and establishing the foundation and, you know, iterating and iterating, you never stop iterating, but iterating to a place of like, we know we have a really good business model. We know what works. We've, we figured out a way how to, how to really make it sing. But there's a ton of value for us to, to really unlock out of the brand and the business moving forward. And we haven't gotten to everything. You know, we're still sitting on a hundred years of archives of Far West, Texas, Pancho Villa, you know, came through this area. There's like, there's some really amazing, awesome stuff that's happened through here. We've, you know, we haven't published, we were a content engine, but we haven't gotten into the game of sort of publishing and, and creating experiences besides obviously like the daily coffee shop for a weekly newspaper, the daily and sort of the weekly things that sort of have a bit more reoccurring revenue. Yeah. So there's a lot of ideas. It's the great part is, this is a marathon, not a sprint. And yeah. And I'll at the same time, a lot of conversations about when you do something in a, in an industry that is not so into change and doing things differently, such as journalism, even though they report on change all the time, how has that happened? You know, when I think we started, people were like, those guys are crazy. There's been many moments through local journalism's last 20 years where people have said like, wow, that's a stupid idea. And that's crazy. But I think people looked at us as sort of crazy and insane. And, and five years later, it's like, well, we did it, you know? And so how do we use the, the insights and understanding and, and learnings to help other folks do what we've done? There's a lot of conversation going on about that too.Yeah. How has the journalism world responded to you guys?Yeah. I think now they're, they're like, they're pretty excited about it. You know, we still don't fit the mold. I'm not a journalist. I'm like a still, I've been doing this for five years as like a quote-unquote publisher, you know? So yeah, it's still, it's still, we're looked at as sort of outsiders to a degree, but that makes sense, right? All entrepreneurial thought is really looked at as, as outside the comfort zone. I like to say that like the journalism world isn't necessarily comfortable with being uncomfortable yet. And that's, that takes time and hopefully it'll happen sooner rather than later.Beautiful. Thank you so much for your time, Max. It was a pleasure speaking with you.Yeah. Nice to chat with you too, Peter, as always. And nice to chat about something besides, besides the working on a piece of business. Get full access to THAT BUSINESS OF MEANING at thatbusinessofmeaning.substack.com/subscribe

Sep 9, 2024 • 49min

Michael Lipson on Astonishment & Surprise

Michael Lipson, PhD is a clinical psychologist, author and translator living in Great Barrington, Massachusetts. He is the author of, most recently, Be: An Alphabet of Astonishment, Stairway of Surprise: Six Steps to a Creative Life, and Group Meditation. Michael, thank you very much for accepting my invitation to this interview.Thank you for inviting me. It's a luxury to be invited.So I start, I don't think you know this, but I start all of these conversations with the same question, which I borrowed from a friend of mine who lives in Hudson. She's an oral historian. She helps people tell their story. It's a big, beautiful question, which is why I steal it, but I also overexplain it because it's so big. So before I ask it, I want you to know that you're in absolute control and you can answer or not answer this question any way that you want to. And the question is, where do you come from?Absolute control, what would I do with that? Go ahead, what's your question?The question is, where do you come from?Ah, well, that's a very Zen master kind of question. They often said that, trying to plumb the depths of where the other monk, for instance, was coming from, not geographically or biographically, but sort of from their spiritual source. I don't know if you ever read "From the Mixed-Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler." Well, of course I did. And in there, there's a little boy who's hiding in the Museum of Modern Art or the Metropolitan from the guards and the boy and a girl. And at one point, the boy is hiding. He's standing, I think, on a closed toilet. But the guard opens the stall and sees him and says, "Where did you come from?" And he says, "My mommy always says I come from heaven." And then he runs away. So I guess that's where I come from, just like you and everybody else.Where do I come from? Sure, I could just answer that in so many ways. To be more down to earth, I was born towards the end of the 50s, a baby boomer in New Haven, Connecticut. My father was a professor at Yale, which certainly had a big effect on me, not only because my mother also was a professor more briefly. And at UConn, she got her doctorate in American history. My father's field was law, in particular, international and Soviet law.It had a big effect on me because of a kind of a reading, academic orientation, fundamentally, and the people we knew and so forth. But also because though I was Jewish and raised in an agnostic background, my dad, to a lesser extent, my mom, but definitely my dad had an early interest in Zen Buddhism. That was like an academic, fashionable, almost intellectual thing. Back in the day, he wasn't a sitter in meditation or an attender of workshops and so forth, but he was a reader and thinker. So, I grew up hearing stories of the Zen masters and the wonderful old Hasidic rabbis, sort of as if they were all one group of fascinating people. And I think that had an effect on my siblings too, but it took a little more in me.So, I think that early wondering about the nature of the mind, the nature of our project of being here, what this is, the Zen people talk about the great matter of life and death. I would say also the fact it's a spiritual kind of a background or, I don't know, psychological background that's very fundamental is that my parents' first child died when he was just three months old in a car crash. And so, my parents were driving. My mother was holding the baby on her lap. This was before car seats. And my dad swerved to avoid a dog in the road. The car hit a soft shoulder, flipped over. My mother fell on her firstborn child and killed it, as she said, with her weight. So, that was a kind of untalkable about thing, you know, and a grief that I think pervaded my family when I was growing up. And one of those things that's an open secret, where to some degree people know about it, but it can't be talked about. And I think that had an effect on all of us, sort of making us have some kind of relationship, mostly not a cheerful relationship, to the great matter of life and death. All those are ways I could answer the question, where do I come from?Yeah. You said that it kind of, the Zen, the masters took with you, more so with your siblings. Can you tell me a story about that? Well, like the kinds of stories I would hear from my dad? Or what makes you say that? Is there a moment where you realized that it had took, I guess I love that word, that it struck you differently than your siblings?Well, not a moment, but for instance, I doubt my brother and sister did what I did when I was seven. I remember sitting on the stairs in my home, in our house, and really trying to penetrate the question of mu, which is a Zen koan, a kind of early koan in a series of koans. And it just means nothing in Japanese. And I remember thinking, how can I have it in my mind? How can I focus on it if it's nothing? If it's nothing, there can't be anything to get about it. So I just had an affinity for these kind of puzzles.And do you have a recollection of knowing what you wanted to be when you grew up? What did you want to be?Oh, sure. I wanted to be lots of things. But they weren't a psychologist who writes books on spirituality. They were, I wanted to be, gosh, well, I wanted to be Sir Galahad who occupies the perilous, you know, around the round table in the Arthurian legends. And I wanted to be a cowboy. And what else did I want to be growing up? I wanted to be a poet from very early on. And I wrote poetry into my 20s. Byron said, to be 20 and a poet is to be 20. To be 40 and a poet is to be a poet. By the time I was 40, I was no longer a poet. So he was right about me, he nailed me hundreds of years before I was born.You described yourself as a boomer. Does that word or idea mean anything to you?Yeah. Well, sure. I mean, it's got a pejorative slant since people started saying, "Okay, boomer." But it was, sure, it's, I recognize as a grown up, how insanely privileged we were, growing in a time after the Second World War, where America was increasingly wealthy, increasingly, you know, hugely respected. And it was, you know, as a white, upper middle class American, I was just in an incredibly privileged position, male, which I certainly didn't appreciate at the time. But now I see sort of what this amazing, you know, kind of bolus of a generation, enjoying an unprecedented, and probably never to be repeated standard of living was. So, and then, you know, realizing my cohort is aging and dying, that's, now that certainly is something. And feeling that we were sort of central to the universe, and now no longer. So, that's an interesting trajectory that a lot of people in that cohort are going through.Yeah. Can you tell me a little bit about where you are now and what you do now?Sure. Yeah, I live in Great Barrington, Massachusetts. I'm a licensed clinical psychologist. I've been here many years now. And in full time private practice. Since COVID, a little bit before COVID, I no longer see clients in my office sitting down. I much prefer and insist on seeing them walking in mostly in the woods or talking on the phone while I'm walking. So, all seasons, all weathers, some people want to accompany me, about half my clientele accompanies me, and the others, it's phone or Zoom, but I don't like Zoom. It's better for me to stay awake, to walk in the woods. It's better for my, I have, you know, spinal issues. But also, it's a big revolution in how it feels to be with people.I guess I've always had a kind of democratic, small D and big D tendency. So, there's something very equalizing about negotiating the same fallen log together, or the rain together, helping each other out through going through a puddle or dealing with bug spray and ticks and mosquitoes. You know, you just, it has an equalizing, democratizing quality. And then, too, there's a kind of third interlocutor, which is the surround. Coming up through a psychoanalytic and also, to some degree, family therapy and cognitive behavioral graduate program, nobody ever mentioned the physical surround. It just wasn't, it was just all about people's habits and thoughts and feelings and history. But it wasn't. You're actually somewhere on a planet, in a man-made surround, or out in the woods, as I am now.And to actually realize that there's no such thing as a human just floating in space. There's a human with, of course, a history, that's a kind of a surround or environment, and a human kind of biosphere, the people you're connected to professionally or through family or friends and lovers and so forth. But there's also the material world that we're part of and embedded in and surrounded by, whether you think of that as an animal world or a biosphere altogether, or everything else, the mineral world, world of air and earth and water. And of course, our so-called man-made surround, if we're in a building, there's wood and metal and plastic and paint, all those things are also nature, just transformed by us. It's almost as if we see them as something utterly different from a tree or a rock or a river or a donkey. Well, they're very different, and we've transformed them and denatured them to hugely, so they're not recognizable, but we got it all from the earth. It's all earth.If you look at a, I don't know, a computer, every single thing is mined from the earth and then hugely transformed by human intervention, but it's all earth and we can have a relationship to it. That relationship is psychological, but also energetic. Now we're getting into a more mystical or magical or wondrous thing, but one of my many trainings was in kind of energy medicine or energy relationships. That's a California thing from back in the 80s. But that's a very real part of my life and I think everyone's life and part of our connectedness with the world.You mentioned that it was COVID that sort of shifted the way you are with your clients. I just had a conversation with somebody who was talking about their experience in psychoanalysis, sitting on the couch, lying on the couch with the therapist behind them, like a New Yorker cartoon. It's not something I've ever experienced. I didn't know that it was still going on. But how big a shift is it, what you're doing, and how did COVID bring it about?Well, it's a huge shift that does exist, but it's not very common. The old style New Yorker cartoon set up, which was Freud's set up, which by the way, comes from Anton Mesmer. Mesmer had people lying down, hypnotism, hypnos, that's sleep. Hypnotism was thought of, mesmerism, hypnotism was thought of as a kind of sleep. So you would lie down and then you would get suggestions. Actually, Freud was no good as a hypnotist, which it's very well known, it's part of the literature. He was bad at hypnotism, and he ended up inventing psychoanalysis, or actually a patient of his, Anna von Oh, who we now know was, that was her, the name he gave her for confidentiality's sake. Actually, we now know it was Bertha von Pappenheim, who turned out to be a brilliant woman and is really the founder of modern social work.And she said to, actually, she was a patient of both Breuer and Freud's studies in hysteria, 1899. Joseph Breuer was a colleague, another neurologist and colleague of Freud's, and she was his patient originally. She told him, please shut up and listen. He was telling her what to do, telling her what she thought, telling her what the source was. She had some very odd kind of symptoms. And she said, you know, I think it would go better if you just shut up and let me talk, I mean, in the language of the day. And he was wise enough to do that. And then she started talking and things started to go better. So the whole idea of the blank screen analyst and so forth, comes from a woman. Now I mentioned that because, and then credit went to Freud and Breuer.But I mentioned that because actually, it was many years before COVID. I had a patient and a middle aged woman who, I don't think it's right for me to say her name, even though she's long dead. And she had terminal ovarian cancer. But she was told by her doctor, you've got three months to live. And she said to me, "Michael, I'll pay you for your whole morning. I want to climb Monument Mountain, largest mountain in Great Barrington." It's only, I don't know, 2000 feet high. And she said, "I want to climb Mountain with you. This is before cell phones. And when we get back down, I want you to call Dr. Johnson and tell him she's not dead yet. She doesn't look like she's about to die," which I did. And she was very happy with that. It took us a long time to climb because she was already in pain and not doing well. But she ended up living another five years. So she was quite right.Anyway, that got me out of the office, if you see what I mean. And I had one other episode like that long before COVID, where I saw a little boy in therapy. And it was a terrible first session, really. After the session, his mother said to me, "How did that go?" I said, "Well, it wasn't very forthcoming." And she said, "You know, if you walked in the woods with him, I bet he'd be more voluble." So the clinic that I was in then was right, there were some woods right behind it. There was a little river, a little stream with rocks in it. So next time he came, he and I crossed the stepping stones across this stream. And we went into the woods where no path, we just went into the woods behind it. You'd never do that now without permissions and so forth. And as soon as we crossed the stream, and we're in the uncharted woods, his gait changed, his kind of face changed, and he started talking about all kinds of things. So she was right, the mother.But that also got me out of the office. So then when COVID came, and we had to have, you know, six feet or more distance, and you're supposed to be outside, or many of us bought special air purifiers for our offices, which I still have also. But then I arranged with some people to go outdoors and meet them. Even then, I remember being anxious and wanting to walk sort of at a distance from people. That was before the vaccine and everything. So then I felt like, oh, this is kind of great. This has a lot of different qualities, this walking, sometimes on city streets, but mostly in the woods, with patients. And so then I gradually decided this should be a full time thing. And I'm sick of sitting in the office, which I did for 30 years before that. So it's okay to go through a change.How did you get into the work that you're doing? When did you realize that you would make a living doing this kind of work?Oh, well, it was a tortuous long process. So I have a lot of sympathy for young people who go through a lot of torture finding their way in life. Let me see. Well, as I said, I was raised in an academic family, and I was good at things like analysis of literature. And in the fullness of time, actually my undergraduate major was German literature. And I read German literature, because I was interested in the poet Rilke and in the works of Rudolf Steiner, who I'd run into also. I wanted to read Steiner in the original and Rilke's way better in the original. So and then I eventually, in the fullness of time, was at Yale in a doctoral program in comparative literature, with German, French and English being my languages.But, you know, things I had seen before, like working with Mother Teresa in Calcutta, it was just so dusty and empty to be in these theories. It just didn't cut it for me anymore. And I'd grown up with it. It was really like I'd already done it. It wasn't news to me. And I felt dead. And I had some prophetic dreams or suggestive dreams and so forth. And it was really hard to leave because being at Yale incomplete, my whole academic career was assured, you know, and it was very hard for me to leave. But I was in my late 20s at that point. And I, but I quit after a year and floundered for a while. I didn't know what kind of, I wanted to do something helpful to the world. So eventually I got a doctorate in clinical psych.But I think that one thing that made it impossible for me to stay as an academic was my time in Calcutta, although it was brief. But after graduating from college, I got a fellowship, the Sheldon Traveling Fellowship from Harvard. And they, my project was to go live with Mother Teresa in Calcutta, which I did. Not with her because it's a very, it's a very gender segregated organization, still very traditional. So I lived in a novitiate house with some brothers, some of the missionary brothers of charity, and worked in Kalighat, the home for dying destitutes. So we scraped up these dying people from the streets and I turned TB positive there and was exposed to a whole bunch of diseases and got very, very sick with dysentery. But of course, none of that was really anything compared with the incredible depths of disease, poverty, suffering, abuse that you see there. I won't go into that in detail, but you see a lot of distressing things there. I was also somewhat distressed and confused by the whole way the Catholic church and Mother Teresa had of treating people or ministering to people. Nevertheless, it was a fantastic experience, a big education for a white kid from America.I mean, to the best of your ability, what was that experience like? I mean, my first, I've been to India and my first experience was on the streets of Calcutta. Nothing like what you're talking about, but just the mere exposure to the streets of Calcutta was enough to just blow my mind really wide open as to just how different life is out there in the world. I don't even know how to talk about it really, but what was your experience? How did you come back changed from that time?Well, I just felt the absurd luxury of our world here. That changed me. But also I'd been kind of blasted open by the amount of love and compassion that was there in the missionaries of charity sort of in spite of everything. It's not like I believed in the Catholic doctrine, but they were doing something just amazing and trying to help people in their way. And, oh gosh, I remember one of my first days there, there was a guy coughing into a little clay cup. He had tuberculosis and he's spitting blood and he was gesturing, of course, I didn't speak any Bengali. He's gesturing to me. He wanted to be shaved. Now he was kachaksek, emaciated, covered with sores, dying of tuberculosis, but he wanted to be shaved.So they gave me a straight, I mean, not a straight razor, an old fashioned safety razor, which as you know, isn't very safe. And there was no shaving cream or soap. They gave me a little thing of water and this terribly dangerous, dull, safe, quote unquote, safety razor. And I had a little shard of mirror. There was just a broken shard of mirror. And I shaved him and with every stroke, the blood would come because his skin was just paper thin. But I showed him as I was going, both the blood and the fact that some of the beard had come off and he was so delighted and was going, come on, keep going, keep going. So I shaved him in this frightening way. And then he died that night. Next day when I was there, he was dead. He was gone.So those kinds of experiences, seeing people with, you know, missing limbs and I went to a clinic for people with leprosy and just alarming things. So it changes your sense of what is this world that is presented to us in such a sanitized way through our media and our direct experience here. A lot of white, relatively well-off people, well, a lot of people of all colors and genders and nationalities, but people who are relatively well-off in America never experienced the pervasive poverty, disease and so forth that you see in other countries. At the same time, I have to say there's a level of connection among people that far exceeds our loneliness. So those kind of cross-cultural, what we now, people are familiar, I suppose, with that idea. I certainly confirmed that.Which idea?The idea that we have no idea how privileged we are. And that can be told you. I grew up hearing about the starving kids in Africa, so we should finish our food. But you can be told you, but of course, going and experiencing anything makes a world of difference. Same with spiritual practices and realities. You can hear about them, you go, oh, this sounds pretty, or this is nice, or whatever, nice theory. But when you experience anything, it changes you.Yeah. I feel like I remember a conversation with you where we shared this song, "Do You Realize?" Is it The Flaming Lips?Yeah. The Flaming Lips, yes. It's wonderful.This amazing song because it captures this kind of feeling. You've got two books, right? One is "Stairway of Surprise." And the other one is this "Alphabet of Astonishment." And I guess I wanted to ask you about what makes those things so important, surprise and astonishment and realization, I guess. What's your attraction to those ideas? And what have you learned about them?Yeah, thank you for pointing out. The "Stairway of Surprise," and it's actually called "BE," B-E colon, "An Alphabet of Astonishment." But yeah, surprise and astonishment are in both those titles. I do have a third, "Group Meditation" about a kind of a technology of spiritual experience in a group. But what's so important about surprise or astonishment, or I could mention a bunch of other things that are kind of in the same family, like curiosity, or wonder, or gratitude. These are all qualities that open your mind, that soften the edges of what you think you know, that make you available to new understanding.The Zen, the Korean Zen master, Seung Sahn, who died, I don't know, 10 years ago or so. He had a lifetime slogan, "Only don't know." He didn't really quite mean only don't know. He meant don't know the way you already know. Don't know. Drop everything you think you know to, of course, have new kinds of experience that don't necessarily grasp anything. It's the difference between, if I reach into a river, let's say I want to get some of the water in the river, I want to know what the river's about. If I reach into the river and grasp with my hand and pull away, I have very little water in my hand. But if I reach my hand in and leave it in the river, I have the whole river.Qualities like astonishment, wonder, surprise, curiosity, gratitude, you can wash yourself through with the quality of innocence. Not that you've never done anything wrong, but it's a state or quality of mind, of innocence. Those things open us. They're like, another Zen teacher refers to opening the palm of the mind. Opening the palm of the mind instead of grasping and quote unquote, having some understanding or some knowledge. Opening the palm of the mind.These are all ways, these words are just cues to the tip of the iceberg of various practices that return us to a state of cognitive non-grasping by which all kinds of interesting things come your way. William Blake, the 19th century, well, late 18th and early 19th century English poet has a phrase, "He who binds to himself a joy does the winged life destroy. He who kisses the joy as it flies lives in eternity's sunrise."So no binding to yourself, but kissing or appreciating it, gratitude, wonder, awe as it goes past. So flying or flowing, either way, not something to hold. So we need to train our minds away from getting the right answer, having the right doctrine, thinking we understand, train our minds to an openness that can bring us into greater intimacy with the universe. That takes various kinds of spiritual practice. So meditation, that there are many, many kinds of meditation, but there are many other things of the spiritual practices that don't quite, aren't meditation, but they're also restructuring how we know, how we live, opening our hearts to compassion for other people.I think the time in Calcutta, which probably I was oriented that way because of my family's deep history with a death that couldn't be faced. I think it furthered my amazement at the fact that we do exist and we are alive for a while. And sharpen the question, what do you want to do? As Mary Oliver says, what do you want to do with your one wild and precious life? Sharpen that question. So it winkled me out of the academic career and into a career of helping people. You can't do that as an academic. I think I could have stayed. It would have been fine. There are plenty of wonderful professors who do wonderful, amazing things for people. So I'm not saying it was necessary.I'm curious about the role of literature. You're always, you always have a quote. You always ground everything in language or literature or poetry. It's always really amazing. You say you started with Rilke. I have this real attraction to sort of the German idealism and Goethe. What is it about Rilke and Steiner and the German imagination that's so powerful? They're all unique. I'm not sure I've ever grouped it really into thinking, I don't know, the German mind or something is so wonderful. But it's true that idealism and a lot of important authors came about and the romanticism really started in Germany and so on. I'm not sure why that would be Rilke. You're a romantic or an idealist?I think they were onto important things. People like Novalis, also Friedrich von Hardenberg, younger contemporary of Goethe's. Of course, Heidegger has the kind of flowering of the German Seinsphilosophie, or being philosophy. I'm not quite sure how I got led there originally, as I think about it. How did I first hear about Rilke? Or why did I decide to major in German? There were a lot of factors behind it. My dad, again, was a big lodestar for me. He was a huge quoter of poetry. He knew French, Italian, German, Russian very fluently. And so I started memorizing poetry when I was very young. Poetry and to some degree, passages like speeches like the Gettysburg Address or things like that. I enjoyed memorizing.And I think memorization for me as a kid, and even today, it's kind of taking a break from your own mind. It's like I have this, the repetitive worries, or just repetition altogether of your own thoughts, isn't as interesting as repeating very beautiful, elevating, suggestive, intriguing, challenging thoughts of others. So hopping out of my own mind into the minds of others. And then I guess, yeah, it really has to do with the beauty of the language, whether it's Rilke's writing or English-American poetry.What do you love about Rilke?Oh, sorry. Well, Rilke knew everything. He just knew everything. Now, Rilke, mind you, I read a wonderful takedown biography of Rilke and what an a*****e he was in interpersonal. I'm not sure he's my favorite person, but in terms of his poetry, he got himself into a good state to write his poetry. And he understood, you feel that he understands the inside of the world. It's like this whole world, our thoughts, our feelings, the physical world we see is kind of like a result, a clunky result. It's like the ice cube that forms, but the fluid river that coalesced into these fixed forms of thought, feeling, perception, memory, everything. You feel that Rilke's in the living stream before it coalesces and dies into the everyday world. And his poetry kind of teases you backward and upward, which, by the way, is a famous trope inside of Zen also, is to take what they call the backward step.That's why that question, where do you come from, your first question, where did this thought come from? It doesn't belong to any particular person. I remember there's a Quaker story that some early Quakers were sitting with their Native American friends. They invited a Native American elder from somewhere around here, the Mashapauga, one of the East Coast tribes. And after a silent hour, the elders, the tribal elders said to the Quaker elder, it's so good to spend some time in the place where words come from. So one feels that Rilke and the great poets altogether are teasing us back to the sources which are actually livelier than the results, the processes livelier than the results. We're familiar with that idea.Yeah. So I shared with you just a little while ago, because it crossed my path that Pope Francis had written this thing about the role of literature and formation. And I just wondered if you had a chance to think about it, what your thoughts might be. He wrote this, I mean, I guess he writes these papal letters all the time, but I don't, of course, I'm not always paying attention to them, but this one crossed my path through the Chronicle of Higher Education, because they were saying, can the Pope save the humanities? Because he'd written this letter about the benefits of literature and formation, which I think is the technical term for the development of a person in the church. But he says in the first paragraph, this is open for everybody. And one of the first benefits he sort of points out of literature is just this idea of empathy. And I guess I'm curious to hear you talk about, we talked about wonder and all that other stuff, but empathy, and you spent all this time listening and being with people. Maybe you're not listening. I don't know how you describe what you do when you're with patients, but how do you think about empathy and what's happening when one does empathize with another person?Yeah, I think literature opens our minds and our hearts to not just the human condition or our own condition, but other people's conditions. And one of the key things for meaningful empathy, compassion, treatment, etc., is to let the other person be other. That is not to assume that what they feel, what they suffer is just what you feel. So you can empathize, you can sympathize. I think literature, biography too, certainly helps us to imagine minds and lives and sufferings and joys for that matter, other than the ones we already know.Montaigne had a slogan, that he had written over one of the beams in his office, Michel de Montaigne, meaning nothing human is alien to me. So he too was interested. He would read about cannibals, you know, was a new thing in the 17th century, learning about cannibals in remote areas in South America. And he wanted to feel, you know, I can imagine that. So he wasn't pretending he was that, or he already had done that. He was interested precisely in the new and yet feeling, even though it's alien, it's not alien, even anything human, I can somehow embrace, have empathy for. Let it be other and then let it not be other. That's empathy.Simone Weil, W-E-I-L, who I mentioned extensively in the book, "Be an Alphabet of Astonishment," she died in 1943, a brilliant student at the Sorbonne. She wrote a wonderful little essay, a classic of 20th century spirituality called "Reflections on the Right Use of School Studies with a View to the Love of God." So that may be whispering in the Pope's ear still, but the right use of school studies with a view to the love of God and what she says. And by the way, she ends the essay on the topic of compassion, because she says the real reason we learn things in school is not to have the content, but to learn to pay attention. And that comes to its highest form in prayer and in empathy, compassion for other people.So only someone capable of attention, she says, is capable of really helping another, being oriented towards another. So there we have prayer and meditation, how properly they develop a meaningful kind of selflessness, not as a mask or a principle, but as an actual orientation of the mind that can empty itself of itself and be open to the other. School studies, literature, imagination can be helps towards that end.I'm curious about your take on sort of the current state of things, I guess, you know what I mean? That we've only got a couple of minutes left, right? But you spent a lot of time with people. You're talking about attention. My mentor would say that we consume the thing that we're afraid we're losing. And that I feel like everywhere I go, people are talking about mindfulness or the attention economy that we're very, very focused on our attention right now. How do you think about what it means to try to be astonished or surprised or curious or open in 2025 when our attention is so occupied?Well, yeah, attention, like every other word can mean, can be a slogan that means so many different things. But what's rarely talked about is the deepening or the intensification of any of these capacities. They can all be infinitely deepened. So the attention economy and so forth, that has to do with an attention deficit disorder. That has to do with our attention being ripped around by a million things, social media and everything. And people are coming through that to realize the importance of where we put our minds intentionally or unintentionally.But rarely is it spoken about that the attention can be deepened, the consciousness can be deepened, intensified intentionally. There is a, in the Frick Museum in New York City, there's a picture, I don't know who it's by, a medieval picture of Saint Jerome. And the title is "Saint Jerome Reading." So he's obviously reading the Bible or some holy scripture. And so the book is in his hand, he's holding the book, but he's looking up in a way and says he's reading. He's not looking at the book because what he's doing is he's taken something from the book, he's read a passage or a sentence, and now he's letting it sink in deeper.Now he's working with it before he goes on rushing through to finish or jumping up to do something else or checking his iPhone. He's staying with what he's already read and deepening his sense of its validity, its reach, its life. So our staying with things and our letting the world and our own minds grow in intimacy and significance, that's more rarely talked about. That's not what we mostly mean when we talk about attentional problems or the attention economy or thieves of our attention these days. It's related, but it's only at one level.Beautiful. Michael, thank you so much. We're kind of at the end of time, but I really appreciate you joining me. Thank you.Thank you. I really appreciate your questioning and your receptive silence that invited me in. All right, take care. Be well. Get full access to THAT BUSINESS OF MEANING at thatbusinessofmeaning.substack.com/subscribe

Sep 2, 2024 • 1h 16min

Kate Sieck on Theory & Practice