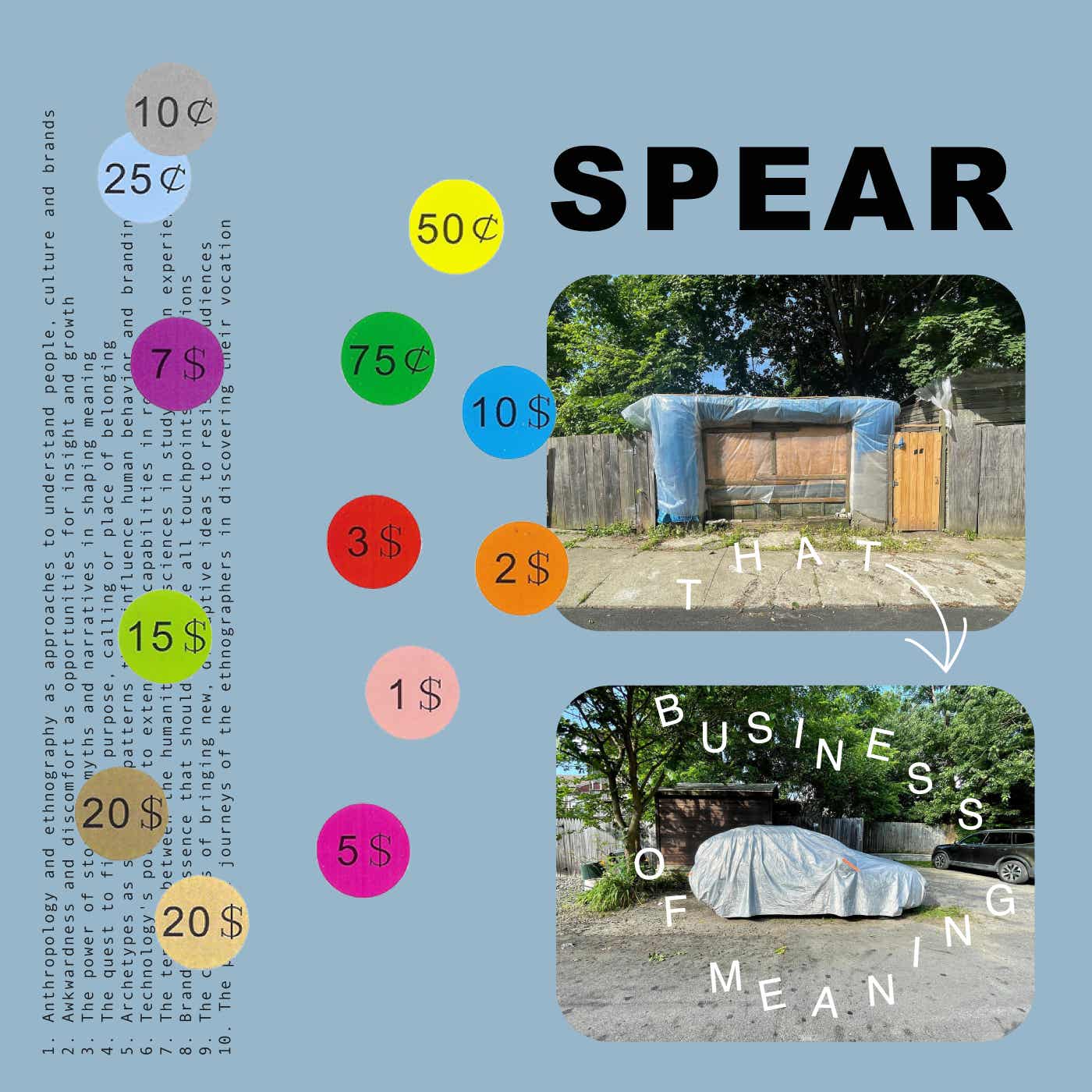

THAT BUSINESS OF MEANING Podcast

Peter Spear

A weekly conversation between Peter Spear and people he finds fascinating working in and with THAT BUSINESS OF MEANING thatbusinessofmeaning.substack.com

Episodes

Mentioned books

Feb 19, 2024 • 35min

Kirsten Bell on Anthropology & the Everyday

This is the third in a series of conversations I am going to be having with people who make me wonder. Look for them every other Monday.I first encountered Kirsten Bell - the anthropologist, not the actress - by way of her piece, “Do Washing Machines Belong in Kitchens?” and was hooked. Since then, I have been devouring her newsletter, Silent But Deadly, and looking forward to her book “Silent But Deadly: The Underlying Cultural Patterns of Everyday Life.”Where do you come from?Ah, yes, I can see that there are, it's a Rorschach test, isn't it? Where you go with the question. But obviously, in a literal sense, I'm Australian. Originally I moved around a fair bit. So I'm an anthropologist by training, and I suppose as a result of my work, I've done fieldwork in South Korea, I've lived in the U.S., in Australia, Canada, and I'm currently living in the U. K. I have answered your question in a very literal sense. What did you want to be when you grew up? Actually, very unusually, I wanted to be an anthropologist. Most people, I can say this from years of teaching, most come into anthropology in a fairly accidental fashion. It's something they discover at university rather than something that they want to be. And I think that's just because there's not a lot of understanding of what anthropology is.But for me, when I was 11 or 12, I saw a movie called The Serpent and the Rainbow. It's a very loose adaptation of Wade Davis's book of the same name. It's a horror movie Wes Craven. And I actually don't remember that much about it, except that it was about this anthropologist who goes to Haiti to study voodoo.And at the time I was very into the occult, witchcraft, unexplained phenomena. And so when I saw this film, I was like, wow, there's a job that you can do where you get to study this stuff for a living. And so right from the age of 12, I decided that's what I wanted to be. I went to university to study anthropology and become an anthropologist and never really deviated course from that point.PS: I remember that movie very well, and I don't know, I think it was in the, I've seen it a few times, and it had a strong impact on me too, and what I remember, I think, is a line from the movie that they used in the marketing of it, is what he would say in this gasping voice, he would say, Don't let them bury me. I'm not dead.Yes, that's right. It is a horror movie and I remember, I don't remember that much about it except for yes, him being buried alive. And then there's a torture scene where I think he gets a nail through the scrotum. So yeah, it's yeah, but it obviously did have a pretty substantial impact on me.It's funny, actually, lots of movies, like the films that tend to feature anthropologists are mostly horror films.PS: Is that right?Yeah.PS: What other movies come to mind?So I guess the most recent one would be Midsommar. So that's the one, they're all graduate students in the U. S., I think, for students who go to Sweden to study this summer festival and it it's a terrifying, it is a terrifying film anyway, it's, that's the latest one, but I guess The Relic that would be another one, Anaconda.Yeah, there's a bunch of movies that there's an anthropological analysis on why that is, and this idea of the anthropologist, there's a mediator between different realms. The fact that often there's a certain kind of expertise anthropologists might have in non-Western context, and so that the films where it typically features is a, obviously Anaconda midsummer, they're set in a certain cultural context where, you know, the presence of an anthropologist might make sense. But yes, anyway, random fact.What do you make of that?Yeah. So I guess. Yeah, I think it's a slightly maybe romanticized explanation, but it's this idea, of the anthropologist as a mediator between different roles. And so whether that's a sort of Western or non Western, they're the human and they're the spiritual realm. And so this idea of the anthropologist is a kind of cultural mediator. And of course they often have this role in plot exposition or whatever in, in explaining so called exotic practices to the, to, to the audience in it.Where are you now? Tell me a little bit about the work you're doing and where you're at.Yeah, so I'm in London and so I'm a Senior Research Fellow in Anthropology at Imperial College. So I suppose in my, if my academic work I, my specialty is medical anthropology and so really trying to apply anthropological insights to the study of health and illness.And then I suppose my hobby in terms of the sub stack is very much, I think trying to engage with people outside of academia and show and cater to my obsession with bodily odors, which I mean, I do write an unhealthy amount, I think about that topic, , there's something very freeing about writing for the public rather than for an academic audience, you're very constrained in academic writing.And yeah, I think there's a lot of topics that really aren't considered to be fit for academic consumption that I'm very interested in. And so I get to explore those in my sub stack, and then also hopefully introduce people outside of academia to what a sort of anthropological approach looks like and the ways that was the kind of insights that might offer.Can you tell me a story about medical anthropology, your academic life? What does your work look like? I've worked in various different kinds of areas And so I've done a lot of research on say, on cancer survivorship. And so trying to understand the experiences of people who've lived through cancer, because cancer is a very distinctive kind of disease because it's halfway between an acute disease and a chronic disease. It's one that has existential consequences for the person diagnosed because it has these very powerful cultural meanings. It has a very feared form of treatment, chemotherapy. And so trying to understand. The experiences of people living through cancer based on the fact that it's incredibly culturally significant, but also a very life changing disease.And I've also done work, probably the stuff that's a little bit more related to the work that you do would be stuff I've done looking at tobacco control and smoking. And so I've done quite a lot of work on cigarette packaging because it's an area where of course there's intense legislative attention. So tobacco control is focusing on the cigarette packet as this sort of advertising mechanism to try and encourage people to smoke. And they've tried to invert that, to make that into a sort of anti-smoking mechanism to market anti-smoking messages. And so really trying to understand what sort of impact, if any, that has on smokers, all of this intensive focus on the packet itself.What did you discover?And so there was this sense that in effect, the marketing qualities of the cigarette packet could be used against it. to market an anti-smoking message. Cause there's no doubt that they're not neutral health messages that are on the packet.They're of grotesque imagery with very strong messaging. And so very much coming out of social marketing, which is trying to use marketing principles for, to resolve social problems. But my research would suggest that that's an overly simplistic way of thinking about packaging and that people have much more complicated relationships with their packets that aren't just about the visual.And because mostly obviously when you smoke in a very habitual way, you're not focusing on the visual qualities of the packet. The packet is a container for your cigarettes. And so the research that I done, I've done on the area, which was just in situ interviews with people smoking on the streets, going up to smoking and then saying Can you remember the warning label on your packet? And almost no one could remember the warning label on their packet. And in fact, they would often guess, but sometimes they would say warning labels that didn't even exist.And I think there's an assumption, a sort of, mainstream marketing assumption about the power of the visual that I think in the case of cigarette packaging probably needs some rethinking having said that, I think that So the research that I've done in that area would challenge those assumptions, but it has not been widely taken up. I think we've come so far down a certain policy path that people don't want anything that distorts that narrative.These are much more kind of heavy topics and I think that's partly why with the Substack I want to focus on very light inane, mundane things rather because my professional life is spent studying very heavy topics and sometimes, fairly emotionally challenging or for the people experiencing them like cancer, for example.PS: I encounter acronyms every once in a while in work and they have a very strong feeling against them and I'm going to ask you. Before I, reveal my own distaste for them and argument against them what's the argument against acronyms and how do you feel about them?Yeah, I, when I wrote that piece, I'd recently started a new position in at Imperial. And of course, public health is shocking for acronyms. And the first day I was there, the people must have used at least 50 acronyms. And of course, being, being entering a new job, a lot of what you're doing is just learning the language associated with that. And you know that you can do your job once you've mastered the language. And acronyms are a form of technical language or jargon. In theory, they're supposed to make life easier but in reality, obviously they, I think they have the opposite, they have the opposite effect. And and this is very much about identifying you as a member of a particular community once and excluding people from that community in terms of their purpose, I think.PS: In that piece, there was a couple of pieces of data that I really found pretty fascinating. I guess there's been a threefold increase in the use of acronyms. There was something to about the frequency of usage to that. Most like a vast majority of acronyms are used. They have no life.That's right. They're never, that's right. And I think too, there's some really interesting shifts that have happened, of course, with with the rise of digital communications. And so you've got acronyms happening on different levels. So you've got these professional technical acronyms, jargon. You've also got social acronyms as a result of the rise of, text based mediums, texting. And for me as someone who didn't own a mobile phone until I moved to the UK and still primarily use it as a GPS device, the social acronyms. I constantly have to look stuff up.I really genuinely thought that LOL meant lots of love. Yeah, when I first when I first encountered it. And so there's just constant acronyms. And so they have a social function too. Again, if you have teenagers use very different social acronyms to adults. And yeah, these things I think have a, they're very much around a sort of in group and out group and identifying you, if you know the acronym, then you're part of the in group.PS: Yeah, that's what I end up feeling. It's so exclusionary.It is, yeah. I'm with you. I know. Certainly in academic writing, it drives me nuts when people use acronyms and I'm always, when I'm reviewing stuff, telling people to tone down the acronyms, because I think they make the life easier of the person using them, but they don't make life easier at all. In fact, they, they complicate life immeasurably for the poor person having to try and. Make their way through.And of course, you've got these acronyms that have multiple meanings. And so you can run into problems. I just, yeah, I think the example I use in that piece is PMS. And of course, for most of us, when we think of PMS, we think of premenstrual syndrome, but they're all these conferences like the precious metal summit that use the same acronym. And so there's this sort of constant confusion as a result of the multitude of acronyms and the multitude of similar, the same acronym with, a whole variety. of different meanings.A number of your pieces are about conversation, getting into them and getting out of them. What's your interest there?Yeah, I think for me, again this is very much about just living in different Anglophone countries. And so When I moved to the UK and again, I'd lived, yeah, born in Australia, lived in the U S and in Canada, and there are just certain, differences here in terms of greetings. And I was just a bit, I very confused.So for example, when people would greet me with "Alright?". As a greeting, and it was just one of these things. I just didn't really know what it meant. It struck me as a very odd kind of greeting. And so I suppose for me, it's those instances of going, I don't know what the hell that like, I just being just suddenly stopping and going, I have no idea why people are using that. I don't know how I'm supposed to respond. And yeah, I think for me, the interest in has very much come out of living in the UK. And again, just be experiencing differences that are unexpected and that really manifesting in language.And so I know even when I was living in the U S just, I would use expressions or I would hear expressions that were just incomprehensible to me. And so I was quite surprised at. Yeah, and I had some, embarrassing experiences around yeah, like rubber, pussy. There's certain words that have very different meanings in Australian English, for example, versus American English, and you get yourself into trouble fairly quickly with those sorts of confusions around that.And yeah, I think that's where it comes from. It's just living in different anglophone countries and being surprised by linguistic differences that I'm confronted with and a bit confused about how I'm supposed to respond in those situations.There was an observation, I think, in your piece on greeting is that everybody's lying a little bit. You're always lying about something.Yeah. That comes from Harvey Sachs. He's amazing conversational analyst. They just delving into how complicated conversations actually are. I think if you stop to think about the social minefield that constitutes conversations, we would never ever talk to each other. Because they are fraught with potential confusion, with all sorts of issues. And thank God, they're quite ritualized in how we interact with each other. So we have to lie to keep things flowing smoothly.PS: Yeah, absolutely. It's funny. I'm in my world. There's often too often very popular talk about empathy. Yeah, when I'm asked to talk about empathy. I prefer to talk about awkwardness is you're exploring awkwardness in a way the way that I understand it. That it's this experience when the script kind of falls away and we're just left with no idea ....what , who we're supposed to be or what we're supposed to do. What's the appropriate kind of we've lost the script and we can.Yeah, I think that's an excellent way of putting it, actually. And I would say almost in some respects, anthropology as a discipline is intrinsically connected with that sense of awkwardness, which is putting yourself in an awkward, radically different, culturally different situation potentially, and then not knowing at all what to do, and then learning things out the hard way, and then in the process, challenging your own assumptions, because it's why is this awkward?What makes it awkward? Why am I feeling that way? I think there's something, there's a lot to be learned from that feeling of awkwardness. So that's an, I think that's an excellent way of yeah.What do you, can you tell me more about how you've learned from awkwardness? I feel like you're identifying, I'd love to hear you talk more about the role of awkwardness in your own work.When I've moved from country to country finding awkwardness where I didn't expect it. And so when I was doing, so my PhD was looking at a religious movement in South Korea. And my original research was in a radically different cultural context where you're confronted, with pretty radical cultural difference, but you expect that. And so I was constantly committing faux pas, especially in Korea. It's very there's fairly firm social etiquette. It's a fairly, hierarchical etiquette.And so I was, I can remember I, as an Australian, I wouldn't be thinking about if a meal was served, I would start eating. Not waiting for someone who was more senior to eat.I remember being in a religious service that was outside. And I knew that if I was in an a ceremony indoors, you needed to remove your hat, that it would be very inappropriate to have a hat on. And there was a religious ceremony I was observing outdoors and I had my hat on and it just never occurred to me that would be considered disrespectful. And someone came up to me and yanked my hat off. And then I was like, s**t, okay. I just. It's a religious ceremony that trumps the setting of the ceremony.So it's a sort of learning experience because you're like, Oh, okay, this ground is now sacred ground, even though it's in an outdoor setting, the nature of the service has made it sacred. And so you learn from the experience of awkwardness. And then I suppose. I was seeing awkwardness where I didn't expect it when I'm, moving between different Anglophone countries.And then again, like when someone greets you with, all right, and you're, it's an, it's really awkward because you're my, I would be like, I think so. And then the person would look at me and I would look at them and I clearly hadn't responded appropriately. And so the whole thing is really awkward. And so then it's that's really interesting. Why is it awkward? Why are they using this word? Why do I not use this word? And thinking that through about what that means. So I think you're right. Almost every piece I've ever written on that subject, a substack is about something like, farting is obviously intrinsically awkward.PS: Yeah. The piece on so much to talk about, but the piece on I guess the long goodbye, which I'm an, I'm American. I don't, I have some interactions with people that are with people in England and but I've had enough that I experienced that though. What do you call it? It's the wall of goodbyes. Is that what it's like?Bye. Bye. Bye. Bye. Bye. Bye. Yes. The wall of goodbyes. Yeah.PS: Which strikes to me in an awkward moment, there's like a panic where you just, there's a total panic and this wall of goodbyes you throw at it just to get out of.That's right.PS: It's just, it's shocking how terrifying this can be, right?So conversational analysts like Harvey Sachs, who I've, I only discovered fairly recently, I don't know why I hadn't read his stuff years ago. This is a guy who spent hundreds and hundreds of hours just analyzing naturally occurring conversations. And so this is where he starts to see all these fascinating patterns in, and they're, they're highly predictable and ritualized the kind of interactions that people have with each other in the context of greetings and goodbyes and all of that. And they sort, they do have to manage what otherwise would be, a tremendously stressful experience that could go potentially anywhere.I think language and conversation and the complexities and dynamics of that are super interesting. And of course, yeah. When you're an American doing business with a Brit and then there's this weird thing that happens at the end of the phone, and it was an American who noticed it actually brought it to my attention.He was like, why the hell are these British, like, why do they say goodbye 10 times? And until he mentioned that it wasn't something I'd consciously registered. And then I was like, yeah, he's right. What on earth is that all about? It's really weird.PS: There was, oh in that same piece about the long goodbye, you quote somebody else who talked, who's just pointing at the fact that this stuff doesn't happen inevitably. Like getting to the end of a conversation required, the language is it involves work and it requires accomplishing.As soon as you start to think about this, it is a bit mind blowing because we just assume that conversations come to a natural conclusion, but if you've ever talked to anyone who is not getting the hints that you're like. Sending you realize that no, actually they have to cooperate with you to end the conversation unless you just want to be rude and hang up on that person. There's a whole sort of cooperative act that's required and it requires accomplishing to get to the end.So you've written a lot, you mentioned it on farts and flatulence and I just wonder where did that begin?The very first academic paper I ever tried to write. So I'd done, finished my PhD and my field work was on a South Korean religious movement. And rather than writing about that, the first academic paper I tried to publish was called Silent But Deadly, Bodily Odors and the Dissipation of Boundaries.Because actually in my field work, I was seeing all these really quite interesting things around bodily odors, et cetera. And so in the family that I was living with, the, the father would fart and just, seeing the reactions to that anyway, it was rejected very resoundingly from the academic journal.And it was, then I just realized that it was not considered appropriate for academic. It wasn't, yeah, it was just considered too, puerile, facile not appropriate to write about academically. And I found that fascinating because anthropologists are living it for the most part they're obviously the nature of anthropological full work is a sort of intensive immersion where you're living in a context with a community for a long period.I'm assuming you're hearing farts. I'm assuming you're farting yourself, but nobody ever writes about it. And I was just like. It's but it's so interesting the whole area because it's this totally natural bodily function that's incredibly symbolically loaded.And so to me, I don't, yeah, I think there are certain areas, that in academic writing have not received the attention they deserve and farting happens to be one. And so I've done my level best to try and address that. But I think as soon as you say farting people, it's not serious. It's not academic.And I know I used to teach a course called being human. And on the first day I would do a lecture on the anthropology of farting and I could see the students. They're like, is this like, why are you talking about this? This seems like completely inappropriate for the students themselves. I just, even though I, I would try and use this as a way of getting them thinking anthropologically and some students would get it, but others like, why the hell is my lecturer talking about farting?This is yeah, it's not I don't expect this in my university lectures. So there's certain topics I think that just, yeah, they're considered too inane, too mundane too facile, too juvenile to be, yeah, considered.PS: What do you say to that challenge? It strikes me as I think it's a wonderful thing that all that you're paying attention to farting and all the various forms. What do you say to the, is it still the case? You think that this is not not fit for academic consumption or what's your argument for, no, this is meaningful. This is part of the human experience.Yeah. So I think there are some people, so I just, there's a book coming out by Berghan called “Matter Out of Place,” which, and I think I, the, one of the editors of the knows my interest in this stuff. And so I was asked to review it. And so the book is all around notions of dirt and pollution. And so people have written about some of this stuff, but even things like defecation, right? This universal process, every society has to manage it. And yet it's massively underwritten about by anthropologists, despite the, incredible significance of shitting.And so there again, so that's changed recently. There are a few people, Zach Van De Yeese, Matthew Wolfmeyer, a few folk who are writing, but there's nothing like the volume of work there should be on something that is so significant.We all have these associations with these things, toilet humor, juvenile, and those associations that we have culturally around those things tend to make the, tend to manifest academically as well. We have our blind spots, academically, I think.PS: I traveled around India with some friends for a while. They have the International Museum of Toilets in Delhi. So the organization that has this International Museum of Toilets is also an organization that's trying to get rid of the, it's creating public toilets so that the caste system is still alive in India. The caste to people whose job is to manage other people's waste. Yeah. And he's trying to eliminate that need by creating these public toilets.. I told people that I was going to go to the international museum of toilets when I was in India and they thought I was a lunatic.Again, it's just, it seemed to be this thing that's fascinating, but in a fairly puerile sort of way. And those prejudices definitely make themselves feel academically. So there is some stuff, but we're all fascinated by these things. And of course, when you're doing, when you're working in a different country. So in Korea, for example, you've got squatting toilets and what you realize is a certain I realize that I just don't have the right leg muscles. My leg muscles haven't been trained to use, to squat, even though probably from a biological standpoint, it makes the whole defecation process a lot easier squatting versus sitting on a toilet.And there's a whole history there. And there is some stuff actually around toilets in particular. There's a great book by a sociologist, David Ingliss.. And what I find interesting though, because the whole book is around the sociology of shitting basically, but he's very careful to couch it in the excretory experience. You can tell reading the book that he's really concerned that to show that he, this is very serious scholarship. And so the whole thing is a lot more inaccessible than it should be in terms of the language, because he's trying so hard to convince the readership that this is a serious piece of scholarship. And it is a serious piece of scholarship and very good. And it's, it's unfortunate that it's written in the way that it is. Cause I think there's a lot of people outside of academia who would be very interested in it, but the language is a bit off putting because it's so incredibly academic.Tell me more about Mary Douglas and the matter out of place, her definition of dirt, right?Yeah, so I guess she's, she's, these days considered fairly old fashioned in anthropology. She was a structuralist, influenced by Levi Strauss and they were very much interested in cross cultural universals. Especially this idea of binary opposites. So they were looking at really big picture stuff. Which I find fascinating but it's definitely become very unfashionable in anthropology to be focusing on big cross cultural universals, etc. There's a sense that it's, over simplistic, it's decontextualizes things, and that there are conceptual and intellectual problems with that work.And so Mary Douglas, though, I suppose one of her key contributions, she is one, probably she has two very famous books Natural Symbols and Purity and Danger. And one of her key insights was that what we think of as dirt so this is stuff that we consider to be polluting is matter out of place. And so she very much in this frame that you have categories and things that don't fit the categories, tend to be considered to be powerful and polluting. And so she was very interested in bodily excretions, for example, because they're from the body, but they're separate from the body. And so they're the kind of ultimate matter out of place. And so they become very symbolically charged.But she also has those same arguments about things like certain kinds of animals. And so Yeah, so for example, pigs there's, she has arguments about the fact that pig, pork is often tabooed and so from her point of view, that's about the anomalousness of the pig, because it's a hoovened animal, but it eats anything. Whereas most hoovened footed animals eat cud eaters. And so her argument is that it becomes symbolically charged and highly polluting in, is Islam and Judaism because of its anomalous properties. So she has all these sort of interesting arguments about categories, things that defy categories. And those are the things that become charged symbolically and either very powerful or very polluting or mostly both at the same time.PS: I wanted to share. I had a project that I worked on and just talk to you about it and see if anything, it triggered anything. It feels like it's in your sweet spot. It's in the silent, but deadly territory. I did a project for a mattress company. So a bed in a box company. And one of the things that I felt like I observed in those interviews and in those conversations with people was like decorative pillows and this whole idea of making the bed. And it was the first time I really ran into Mary Douglas because it was so obvious how important it was for some people to make the bed, and for it to be very, it's a very special place. This place we put ourselves down to sleep is just unbelievable. It's unbelievable what we're doing for those eight hours. But some places were just unbelievable, so many different pillows and so much decorative. And it blew my mind a little bit. And I wondered if you had any if that triggered any thoughts for you in terms of maybe what does your bed look like? Do you have decorative furniture? What's your relationship withIt's actually a great topic and it's given me an idea for a sub stack. So if I end up writing about it, I'm going to have to mention you. The whole area is fascinating. You're a hundred percent right. Decorative pillows, of course, are interesting because they're quite gendered. And so we tend to find, this was I think, satirized a little bit in the movie Along Came Polly.And so I don't know if you ever saw it, it's a Ben Stiller movie, but there's a scene in where his wife has left him and he's, and Jennifer Aniston is Polly. And then he's got these decorative pillows on the bed and she's like, why do you have all these pillows? You already spent hours taking them off, putting them on. And he was like my wife liked them.When my husband and I first got together, I did have a couple of decorative pillows and he was like, these are completely pointless because you take them off the bed before you go to sleep, right? So they are just, they're not only serve no purpose, they create additional work for you because you're taking them off the bed. You're putting them on the bed. There is an interesting gender dimension to those as well.But yeah, the whole area of bedding in general, I think is again, one of those areas that anthropologists think it's just. Too mundane. It's too inane. And they don't write about it, but it's so interesting.You're saying, it's doing something. What is the work that the decorative pillows are doing? Think, obviously, if you're concerned with the aesthetics of the bedroom space as a whole, then I would say that the function that they serve is as part of a scheme. If you have such a thing in your bedroom, a visual, like a decorative scheme, and it might be a focal point. So it's serving an aesthetic purpose as part of a larger, decorating scheme in a bedroom. And it's a good example of the bedroom being a place, which is sort of your point. A bed has a function to help you sleep, but it also gets tied up into aesthetics, notions of homemaking, notions of Decoration and all of that, that means that you end up with these completely pointless decorative pillows. So no, I have no decorative pillows on my bed as a result of those early conversations that my husband and I had about the pointlessness of of the decorative pillow.Can you tell me a little bit about your book, “Silent but Deadly: The Underlying Cultural Patterns of Everyday Behaviors”?Oh, the book is just, yeah, it's called Silent but Deadly, the underlying cultural patterns of everyday behaviors. And it's really like a series of essays on a whole variety of things, obviously farting. Teeth. Like when I lived in North America, the obsession with white straight teeth, which was very foreign to me as an Australian. Dogs, like dog lovers, I'm not a dog lover. What the whole, like a dog obsession is all about. Tipping, left- handedness. So being a lefty, I'm very interested in, the symbolism and also, mechanisms of handedness. Yep.So the book is just, again, all those inane, mundane topics that aren't considered to be fit for academic attention. And I guess, yeah, Brits keeping their washing machine in their kitchen. That's all the sort of stuff I focus on in the book.PS: Thank you so much. Thanks a lot. Good to talk to you. Bye. Get full access to THAT BUSINESS OF MEANING at thatbusinessofmeaning.substack.com/subscribe

Feb 5, 2024 • 39min

John Walter on Eye Contact & Authenticity

John Walter is the inventor of the TrueMirror. Check it out!!I am the only person in the world I experience in reverse.My self-image is wrong in one giant way. And so is yours. The way we appear to ourself in a mirror, is not how we appear to anyone else. And so, I was excited to discover that, John Walter, the inventor of the non-reversing TrueMirror, lived just across the river from me. Within days of connecting with him in Instagram, he invited me to his workshop to try it for myself.I find the topic so baffling and so full of wonder, I wanted to share a conversation with him. Hope you enjoy. PeterWhere do you come from?Where do I come from? First of all, it's a good thing. I know what you mean by that I come from the Bronx, no, where do I come from? So I think, maybe part of the answer comes from how I solved some of my problems. I had some eating disorder issues when I was in my twenties and I went to some therapists and talked about everything other than the eating issues and really. Eventually I just solved it and I suddenly realized I don't have this problem anymore. And really what the solution was to ask myself, what am I really hungry for? Obviously I was going to food because food was filling this hunger inside of me and it really wasn't filling me up. And so I was eating more and more food and all that stuff.So by asking the question, what am I really hungry for? And the answer came back as experiences. I'm hungry for experiences that, you know, and then when I flesh it out, that are meaningful, that are fun, that are exciting, that are adventurous, that's my, that's where my joy comes from is experiences. Coming from that place where that's what I'm valuing is the essence of the experience. What did that ask of you? So I was probably in my mid, early, early to mid twenties, maybe 24, 25. And I think it just turned the focus again from, because I definitely was looking for experiences. So when I realized that's what I was hungry for, when I realized if I go ahead and get experiences, I will fill that hunger.And I think that's been true. I eat to live rather than live to eat and so that what really nourishes me is connection and people and experiences and fun and adventures, that sort of thing. So it just changed the focus a lot for me.What did you want to be when you grew up?My background is in math and physics. So I was at an early age and singled out to be, Oh, he's really smart. I skipped third grade and was like this, considered to be a very smart person.And so there was a sense of, Oh, I'm going to be this person that has some sort of achievement at the end of my name, which was going and physics was going to be the avenue for it. First of all I became popular in college. I was very nerdy and shunned by my peer group and all of a sudden I figured out why and I changed it and all of a sudden became popular. And that's a long story, but it is actually related to the mirrors.PS: You said you figured something out and you changed it. What did you figure out?So it was basically my hair part. I changed my hair part.PS: Is that right?And if you Google hair part theory you'll see my stuff come up on it. In fact, it was a Radiolab episode I think in 2011, where we talked about it. And not just the hair part theory, but the mirrors as well, the true mirror as well.What is the hair part theory?John Walter: So it basically says that when you part your hair, You're emphasizing that side of the brain to the viewer, okay? And because of a thing called interactional continuity, because hair parts, especially for guys, tend to be on the same side for their whole lives, basically that, it's a bias. It's a little bit like body language, but you're signaling constantly more right brain or more left brain.If you part on the left where the part is on the left, then people will see you as more left brained. If they part on the right, they'll see you as more right brained.And as a guy, we tend to like men who look more left-brained. They're more rational, more logical, more masculine, more assertive, more visible. When you put it on the right, then you're projecting an image that's more intuitive and feeling and holistic, mysterious, feminine, all of these qualities.Now, just a big caveat, these are generalizations that neuroscientists and psychologists can't stand that we use in public. This is quote unquote pop psychology. And yet there's a lot of validity to it.And so what happened is when I was in front of the mirror one day, I had just had some photos taken, and the photos were very jarring. It was like, I'm in front of the mirror going, why do pictures always look so weird?I look fine. And that's when I realized the guy in the mirror was a guy with a left part. And I'm wearing a right part, which when you take a photo, that's a true image. And it was like, eh. So I changed my hair part, I actually put my hair from the right to the left.How do you describe True Mirror to somebody that hasn't encountered it yet?And just to preface it the True Mirror is related to this hair part theory, actually. Because I figured it out about three years after I had found this hair part thing and eventually was doing my hair in the middle. What a true mirror is a mirror that doesn't reverse your image. So when you look at yourself, you're not backwards. And it's a very simple idea physically. And so there's, I got a little physics in there, but what happens is that what I discovered is that when you make eye contact with yourself, your eyes actually communicate correctly and they don't backwards. And this is brand new.ADDITIONAL LINKS:“Mirror, Mirror” a 2011 Radiolab episode about John. “What is your hair part saying about you?: The effects of hair parting on social approaisal and personal development” a 1999 paper by John and his sister Catherine Walter“The Mirror of Dorian Gray: Mirrors never lie, they say. But how much truth do we really want?” The Atlantic by Cullen Murphy in 1999'It's in the entire time that such a mirror was actually a thing, it was patented in 1887, no one saw it as anything other than the physical. And yet, when I first saw it, it was like, Oh my God, there you are. And this connection to myself as a kind of a happy, having fun kid on the beach in California, okay, was amazing.And part of the story is I, I was and I guess now because it's legal, I can say this, but I was high as a kite and I was just flying and I walked into the bathroom and the regular mirror just shot me down hard. And that's when I saw this double mirror combination, which is all it takes to make a mirror. True mirrors is two mirrors at right angles. Although, mine, and then I turned the corner and there was this double mirror, and I did a double take. Because I saw something that I recognized. I saw my happiness. I saw the sparkle in my eye. When you're smiling, the light of your eyes in the smile is why you're smiling. And when you flip your eyes in a mirror, you lose that why, and all of a sudden you're just looking like you have a fake smile.If you think about it, you've had that interaction with yourself since you were a child, and you've completely identify with that version. And then all of a sudden I saw myself in the double mirror. I did a double take and I spent like five minutes just absolutely loving on myself and there was so much of All this crud, this self doubt and challenge and struggle just absolutely disappeared. I felt like I'd taken a showerAnd that kind of forms the passion for why I get so into this mirror, because it really fixed me, my internal self image, the main thing is, I'm okay, I'm normal. There's nothing there's nothing abnormal about me, which I see, I still, to this day, I still see in the reverse mirror.What was the journey from that moment to choosing to develop a mirror?So interestingly, because this is part of the story of this. I immediately started to show people. It's yo, check this out, and they didn't get it. It was like, what are you talking about? And, I said no, can't you see the light in your eyes? And it's the people just, I got nowhere.I figured, okay, maybe it's that line in the middle, that's causing it to be too distracting. And so it was like, maybe I can bevel the mirrors and I did all this stuff to try to fix it. and then About 10 years later, it really took that long. And I was so excited, because it was like, wow, I can actually make this so that it actually, people will see what I'm seeing.Funny story, they still didn't see it.The main thing is that I believe is that because the mirror has not been reflecting us in our natural expressions since childhood, we just stopped doing them. We come up to the mirror, as soon as we see ourselves. We shut down and it's just this hardwired neurological pattern that is very common for people. And so if you show up to the true mirror with that same pattern of just shutting down, it's not going to show anything. And so trying to get people to, to interact with themselves is one of the big elements that I discovered makes this experience actually come alive for people.PS: If I'm wrong, tell me I'm wrong- is that we are conditioned to have a non-interactive interaction with a conventional mirror. So people approach the mirror without expecting any interactivity. So that’s an interesting possibility, but it's not the real story, not the full story. Because you can't not interact with yourself. It's just at this other level, and part of the other level is that your face is not part of the communication, usually.Your brain is still thinking, but your face is not reflecting what you're thinking. Like , those circuits have been turned off. And this is where I think it's a real problem, because you're interacting with yourself without your expressive personality, and you're identifying with this kind of mask-like version, and you'll tell yourself stuff, like about how you're feeling what you're thinking about what's going on.And the sad thing is the expressions that really convey positive elements of your experience, like your happiness, your joy, your vibrancy There's a lot of activity in your face with them. The expressions that are more sad and down and or just quiet or they don't have a lot of activity.So it turns out when you show up to the TrueMirror feeling really happy, like I was at that party, those expressions look really patently fake backwards. So you stop doing them. Whereas the ones if you're down and you look at yourself in the reverse mirror, there's not that much difference. The down, down elements still stick around.And in my belief, they get enhanced because there's this layer Of judgment and criticism that kind of goes along with the fact that it's still somewhat fake, and we just don't know it. We just don't know that. The whole world doesn't know that the version in the backwards mirror is somewhat fake.Yeah, I was going to ask, what's the primary difference in the self you encounter in the true mirror versus the self you encounter in a, what do you call a conventional mirror?I'm going to call it a reversing mirror, reverse mirror, regular mirror, standard mirror. I think that the best way to describe the person in the reverse mirror is your doppelganger, it's like almost by definition, it looks like you, but it's not you, doesn't act like you, doesn't feel like you, doesn't express like you.And yet, you think it's you because it looks like you. I think that core element causes so many strange problems. Our self image is built in part on what we're seeing in the mirror. It's built from lots of other things too, but there's this constant element that's in everyone's experience that's not quite real that we interact with in a dynamic feedback loop, that's always got this information distortion going on.And so when you look at a feedback loop, you don't know what's going to happen with it. Like you take a guitar and you stick it next to an amplifier. Any kind of weird sound will start to come out based on where you put that guitar. so Where people end up going with their self image based on this communication feedback loop with distortion is all over the place.It's very strange. One person will be very vain, another person will be afraid of themselves, another person will be, have insane body dysmorphia, another person will ignore themselves, another person will, like in my case, I just struggled.You talked about, anytime that this has been mentioned, it's been explicitly and exclusively about the physical. But you're talking about something else, something different. What is it? What's happening in a TrueMirror?Yeah, I mean to me when you look in a mirror, there's two elements to it: the physical and the personal being. Who you are. How you are. What you're feeling. What you're projecting. What others are gonna see in you. And when you look in a reverse mirror, you're seeing the physical, but the personal gets distorted. The physical does too. But the communication, which is the element of the personal, is what gets altered by being backwards. When you see yourself not reversed, you're getting both the physical and the personal. your right eye and the message of its right eye on the right side where it belongs, left on the left where it belongs. And this is the basis for your expression, and that's how your expressions match.How do you use a true mirror? It seems like a different animal than a conventional mirror.Well, say if this was brand new to you, the first elements are to just discover, what's there what's there that's new for me, it's like finding out what you look like with your real smile. And it turns out that it's a little bit hard to do a genuine smile to yourself. But if you just look in your eyes as your thoughts will flip through your head, your face will start to actually express that.Now I'm seeing me as a person. What did I just learn about me? So when I'm looking at you, for instance, I know what you're seeing. I know how to be authentic, right? Which is really what you need to be doing. And realizing that my expressions are just going to be authentic. I know that if I have the genuine smile, it's gonna have these qualities to it, and therefore I can be comfortable with it. I remember before I was like hiding my smile because I thought it was fake especially my big smilePS: In my work, people often talk about empathy, right? Research is about empathy. And when people ask me about empathy, I end up talking about awkwardness because I think awkwardness is like the frontier. There's a book called Cringeworthy by Melissa Dahl, and she came up with a theory of awkwardness. Which is the irreconcilable gap between how we perceive ourselves and how we think others perceive us. And it's, we get caught in this, this dissonance between, you reminded me of it a little bit when you were, when you described being, the ability to be authentic because you're, you have an awareness. That's how you perceive yourself and how others perceive you are the same. In a lot of ways, part of awkwardness is that we're suffering from this dissonance. We know, on some intuitive level, that the way we appear to other people is not how we appear to ourselves. And we're especially awkward because we know that's not true. I'm going to stop there. What do you make of what I've shared about awkwardness?I agree with where you're coming from. And I just want to add a little bit of the idea that we look different depending on who we're looking at. Okay. Similar. Okay, but my range of expressions with you is going to be different from my range of expressions with someone that is going to be, say my partner. I am different with you than I am with someone else, because it's the conversation, it's the feelings, emotions, it's the levels, it's the degree, it's the depth, all that kind of stuff.When I look at the True mirror, I'm seeing. the authentic version of me, . So I think the goal is to get yourself in sync. So first of all, I learn about myself through you, through my experience with other people. I learned more about myself, but when I come up to the true mirror, It matches, it's like there's not this dissonance. that this doppelganger introduces every time I make eye contact with it,Do you have traditional mirrors in your house or do you have all true mirrors or do you use them differently?So I have the regular medicine cabinet mirror, and I have a true mirror right next to it. And I actively avoid looking at my eyes. in the reverse mirror. So if I'm out and about, I'll go to the restroom at a restaurant I won't make eye contact. It's like literally that's the moment when that doppelganger springs to life. And again, you think about the neural pathways, that's like hard, hard coded, and so by not registering that version of me in my brain, then that whole movie doesn't start. You know what I mean?One of my key recommendations for anyone once they hear about the true mirror is yeah don't even use the other mirror. It doesn't help. It doesn't serve you to connect with that version, which just tells you oddball things.Yeah, even if you like it, you're going to be liking something that's not actually real and I'm saying that Because a lot of people say, but I like my backward self much more and that's usually because you're familiar with it and it's less crooked, but it's not real. . I think that really does a disservice to your mental wellbeing to be connected to this version that doesn't exist.How long have you been making these and how is it going? What's it been like trying to build this business?So it's been 31 years. I started in 1992. So now it's 32 years going into. and like I Said, when I first started showing people, they still didn't get it. And then I would take it around to psychologists and they wouldn't get it. And, so what I found took a really long time to figure out how to talk about it to people.And so it wasn't until probably maybe 10 years ago, actually it was 2003, I went to my first Burning Man, okay, and Burning Man was the first time I had like more than three quarters of the people going, Oh my God, this is amazing.It turns out it's one of the strangest products that you can imagine. You would think, 'cause it's literally applicable to every person in the world. Everyone that has a face is going to have some kind of interaction with this. Unlike any other product, and yet because of that weirdness that's going on, that's deeply embedded in our psyches with the mirror. People are really funky about this.What have you discovered about People that buy TrueMirror? Do you feel like you can pick your customer out of a crowd.I can pick people out of the crowd who will have a good experience, okay? And usually they're vivacious is the best way to describe them. And they can't help but see the difference. But, what's interesting about the coaching is, the biggest complaint I have online in comments is I'm just, it's power of suggestion. this is just b******t. It's Power of suggestion. And I think that it is more of a catalyst like I'm catalyzing the reaction and then, the reaction happens or not, if it happens it's a genuine reaction.In terms of the awkwardness, yeah, I think it's related to the fact that we have this strained relationship with ourself. And again, there's probably a dozen reasons for it, like getting bullied as a kid, for instance, but this primary source of inauthenticity has never been questioned.How has the TikTok, you mentioned you go viral, you get lots of views on there. What has it been like trying to grow the business on TikTok?I think at this point there's 170 million views tagged with True Mirror. They're not all mine. But it's basically a lot. And Instagram, I just had my first million view video that went up. That was great. This algorithm was just designed for this kind of stuff. So it's been great. lots and lots of Interactions, a lot of comments.I really want this to be a helpful thing for people, again, back to experiences we're all hungry for this kind of, being okay with ourselves. And I think it's, if you fix the interface to yourself, you have a much better chance of that.Is TrueMirror is built on a theory of eye contact?It's eye contact with that feedback loop, which is just way more intense. So me and you were in this communication loop and we talked about zoom being Yeah. Disconnected. yeah, it's interesting. You sent some stuff on the ways they're fudging that - using AI to shift your eyes to the lens. Like now I'm looking right at the lens, but now I can't see you.General communication involves eye contact. It's one of the most dynamic things you can imagine in the universe that we know of is two people making eye contact with each other because we're so responsive. Boom, boom. But to yourself, it's amped up even more. And that's where the theory goes is if you flip your eyes, you can't make eye contact with the person behind the eyes. That's where eye contact to yourself, again, for everyone is just absolutely bonkers in reverse, it's not real. It doesn't work. and it's missing so much of what we absolutely know is important with eye contact with other people.PS: No, I feel like the image that keeps coming back to me about my experience of the true mirror is that it called attention to the fact that all my experiences of other human beings are so alive in a way because of this, the eye contact thing, except for my experience of myself. So my own experience of my own appearance is dead, when compared to every other human experience I have with somebody, and it's shocking that's the case and that's the foundation of my self perception is this flat.And you're not alone. This is common. In all the years I Probably just a handful of people could keep themselves really going for more than five seconds in a mirror. Yeah, especially smiles. Almost everyone's smile fades within a few seconds in a mirror. And that's the one that has a lot of light in it,PS: And I wonder too, this is what I'm putting on my marketing hat, the degree to which, the challenge that is that you're moving against this massive cultural, all the behaviors and the questioning and all of the expectations. The culture is so fixed. And the attachment is probably so strong that it's very difficult to see anything other than what is assumed to be there, which is. It's a fascinating challenge as a marketer.It's nuts. And, because You think, oh, this should be great. Improve one of the primary things that every person has in their lives. And then realize, no, there's something else going on.PS: I wondered about that because it feels like you do it with the coaching. In any other kind of Marketing they would be able to build culture around the product. Are there rituals that you are aware of that people have developed around TrueMirror? Sure. the ritual I did with you is the affirmation. A whole thing of, say I love you to yourself in a mirror and, affirm, I am a positive force for good in the world and all of the things that people have that they really want to be.Taking the affirmation concept where you go up to the mirror and you go, I am a force for good in the world, and before you affirm it, you actually ask yourself the question. So you say, am I a force for good in the world? And then you just sit with that for a while. Whatever you come up with will start to show on your face. Your face becomes a dynamic valid accurate reflection of what's in your mind, because that's how they work.So by doing that you're generating the concept in your head and then it shows up on your face and then you affirm anyway. So am I forced for good in the world? Yeah, I'm a force for good in the world. And then you validate, do you know what I mean? Because if it's easy, you go, Oh, hell yeah, I'm a force for good in the world. and you got that strength.PS: I am running near the end of time ....... have you encountered eye gaze that people do eye gazes on instagram? I think it's hashtag eye gaze. And then she'll, I think what she's doing is just looking into the camera, but it's what she's saying or inviting you into is an experience of eye contact with her.So eye gazing in, in practice One on one. Yeah. Have you seen that before? And you just sit in front of someone and you just stare at them?PS: No. Only Marina Abramovich, “The Artist is Present.” Do you remember?That's a very common, exercise with workshops and seminars. Yeah, and I can't stand it, because I need my eye contact to be attached to something as opposed to just staring or just let me be with this other person non verbally. I don't know where to go with it. Other people swear by it. PS: I thought it was striking that she was forming this icon, this, this sort of therapeutic connection on an Instagram account, which of course you weren't there's no it's so strange. Speaks to a hunger to return to the beginning. It speaks to a hunger right that we have for that kind of connection that you get.And part of my belief is that fulfilling that hunger, which is really, “Who are we? What am I about?” Filling that can absolutely take like a dozens of methods. Workshops, reading, interactions Experiences, adventures, eye gazing, affirmations, all that stuff. There is lots and lots of ways to make that add to your experience of yourself. My belief is that the TrueMirror actually works with all of that.How would you describe all of those things? Those are all ways to…?John Walter: you could call them woo wooNo. I'm serious. They're all ways to….what?It's basically self awareness and self understanding in the service of an enhanced experience of your life. The unexamined life, where you are just punching the clock? There is a lot more to life than that. And if you start to search for it, you'll find all sorts of new things to think about.PS: Last question. So this whole conversation I'm using this sort of teleprompter, and in my mind, you're experiencing eye contact. I should be looking directly at you. Have you felt any of my attention or eye contact in our conversation?Oh, that's cool. No, I was noticing that. Yeah. No, I think It's good. It's good. I think that it's good tech, it's good technique. So is it just reflecting off of the glass? Interesting. Of course, are you looking at my reverse face or my forwards face?PS: Oh my god. See, that's the thing where I get dizzy. I can't keep up with all the switching.I'm touching my right eye. Is it the same side as your right eye?PS: Yes.See, so you're looking at my mirrored Image. Yes. you're not Seeing me with my natural expressions.PS: You fix one thing, solve one problem, create another.I'm really appreciating I do see that you're looking right at me. Yeah, but I'm not looking at you. You can see I'm nicer. So now if I look at the lens now I am. I can't see you. So I can't. This is non-interactive. I had that little filter thing. It's because I'm staying with you. It's good. And I'm going to interact with you. So it's interesting, but I like your technique except that it's backwards.PS: We'll get there one day. Listen, John, I want to thank you so much for the time.I'm really excited to have met you and to have seen it.I'm so glad. And it really was fun to say, yeah, I'm just around the corner. And you was like,PS: I had no idea. Yeah, that's cool. Awesome.All right, Peter. All right. Thanks. And I look forward to seeing this and also your other stuff. It looks like you really have a lot of good work here. You've beenPS: Beautiful. Thank you.All right. Cheers, man. All right. Bye bye. Get full access to THAT BUSINESS OF MEANING at thatbusinessofmeaning.substack.com/subscribe

Jan 22, 2024 • 44min

Grant McCracken on Multiplicity & the Future of Culture