Why Structure Matters More Than You Think. Writing Memoir With Wendy Dale

The Creative Penn Podcast For Writers

Character arc versus plot difficulty

Wendy explains that character arc/theme is usually easier than plotting connected events, which is the hardest part of memoir.

Why do so many memoir manuscripts fail to engage readers, even when the writer has lived through extraordinary experiences? What's the hidden code that separates a chronological account of events from a compelling memoir that readers can't put down? How do you know when you're ready to write about trauma, and where's the ethical line between truth and storytelling? With Wendy Dale

In the intro, Amazon Kindle Translate, and the Writing Storybundle.

Today's show is sponsored by Draft2Digital, self-publishing with support, where you can get free formatting, free distribution to multiple stores, and a host of other benefits. Just go to www.draft2digital.com to get started.

This show is also supported by my Patrons. Join my Community at Patreon.com/thecreativepenn

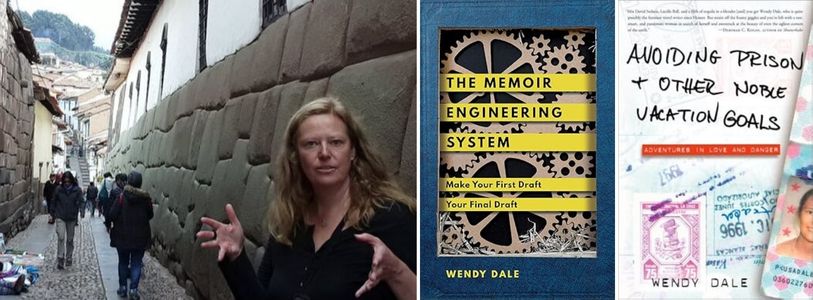

Wendy Dale is a memoir author and teacher, as well as a screenwriter. Today we are talking about The Memoir Engineering System: Make Your First Draft Your Final Draft.

You can listen above or on your favorite podcast app or read the notes and links below. Here are the highlights and the full transcript is below.

Show Notes

- Why memoir is about connected events, not chronological storytelling—and how to transform random experiences into compelling plot

- The difference between scenes and transitions, and why structure matters in every sentence of your book

- How to write about trauma and family without crossing ethical lines or damaging relationships

- Why character arc is actually the easiest part of memoir writing (and what's really difficult)

- The truth about dialogue, memory, and where to draw the line on fabrication — plus reflections on The Salt Path controversy

- Whether you can make money from memoir and why marketing matters as much as writing

You can find Wendy at GeniusMemoirWriting.com.

Transcript of interview with Wendy Dale

Joanna: Wendy Dale is a memoir author and teacher, as well as a screenwriter. Today we are talking about The Memoir Engineering System: Make Your First Draft Your Final Draft. So welcome to the show, Wendy.

Wendy: Thank you so much for inviting me, Joanna. It's exciting to talk about this topic.

Joanna: First up—

Tell us a bit more about you and how you got into writing and publishing.

Wendy: I think I grew up loving books and I always wanted to be a writer when I was a little girl. I really dreamed of being a writer. My mother said, “No, it's just way too hard. So few people have success. Why don't you become an actress?” So I actually moved to Los Angeles when I was 17 to become an actress.

I really did not like the film industry at all from an acting perspective. I was studying acting at UCLA and decided I was really going to be a writer. That was when I changed and really felt like I'd found my calling. That was always what I'd wanted to do.

So I tried writing a novel at 19 that didn't go so well. But when I was 23 I started working on a memoir. From there, I have worked in writing in all different aspects, but really my first love will always be books.

Now having made that decision, I haven't always done the kind of writing that I would always want to do, right? So sometimes I've done ad copywriting, which actually I did rather love. I've done screenwriting, I've done all kinds of writing, not always my first choice of the type of writing I was doing.

For the most part, I have made it work though. So being flexible, you can't always get exactly what you want. I didn't say I'm going to only earn my living publishing books. I don't know if that would've been possible, but I have, for the most part, managed to earn my living as a writer.

Joanna: How did you get into memoir specifically?

Wendy: So I started trying to write this novel at 19, and it was very difficult and I didn't know what I was doing. I thought, well, it would be so much easier to write about my life. Are you laughing, Joanna?

Joanna: Yes, sure. Writing a memoir, right?

Wendy: So another misguided idea. I thought, oh, memoir would be easy because you don't even have to come up with the plot. You just write down what you lived through. Lots of misconceptions in everything I just said, but that was how I started writing a memoir.

Around this time my parents also made this decision that they were going to retire in their forties and take their life savings and move to a developing country. They sold everything. I mean, they really just fled the United States and moved to Honduras with the idea of retiring early.

So I went to visit them and I was like, well, this could be something to write about. So that actually wound up being the first chapter of my memoir.

Joanna: And you were telling me before you live in Peru, right?

Wendy: I do, yes. I've lived in Peru for almost six years now.

Joanna: Oh, right. So, why do that? I mean, a lot of people want to travel.

What is it that brought you to Peru?

Wendy: I lived in Peru when I was a child and really, it sounds kind of strange, but I think deep down I've always had this identity of feeling Peruvian, right? You look at me and Peruvians don't think I am Peruvian, but really, my first memories as a child were growing up in Peru.

Coming back here has been really incredible. So I feel very much at home. I've actually lived by this point, almost half my life in Latin America. Not just Peru—Bolivia, other Latin American countries.

So, yes, I've lived half my life in the United States, the other half in Latin America. So I really do feel at home here, partly because my first memories were growing up in Peru.

Joanna: Well, I think this might segue into why writing memoir is not just “this is what happened,” because I feel like, as you mentioned, one of the misconceptions is almost that it's just an autobiography. Like, this happened, this happened, this happened.

As you said there, for example, the fact that you spent half your life in Latin America, half in the USA, to me is immediately like a potential hook into stories about your life that aren't necessarily in order.

Talk a bit about that issue of it's not just “this happened, this happened” and how to think about memoir.

Wendy: Oh, I'm going to take a deep sigh here because I just think back to writing this memoir and all of the misconceptions I had.

Now, I love prose. I just love prose. I love putting words on the page. I think words are so beautiful. Sometimes I just want to eat them. I'm a prose writer. I don't like structure, I don't like plot, and I didn't even realize the importance of plot until I thought I had finished this memoir.

So first chapter starts in Honduras. The last chapter ends in Bolivia because by this point my parents had moved to Bolivia, and all the chapters in between are all these different countries that I went to on my own.

I'd finished the book, or so I thought, and I started sending it out to agents and really wasn't getting the response I had hoped for. Then finally I got an agent who called me up, and that was really good news, and she said, “You're a really good prose writer.”

I was like, yes, I love writing prose. And she says, “But you know nothing about structure.” And I honestly—are you laughing?

Joanna: Yes.

Wendy: Right, and I remember the words that went through my head. I was like, what is this structure thing she's talking about? I'd never heard the word.

So obviously I knew nothing about structure, and that was kind of the beginning of what I guess would become my life's work—really comprehending memoir structure.

So that was a long time ago. That was the beginning of the process, but I didn't even understand that plot plays such a huge role in memoir. I just thought you wrote about your life, and I think that is what a lot of people don't understand, right?

It's really easy to confuse the memories of your life with thinking that it's plot, and it just isn't. So one thing I tell my clients is you are not writing a chronicle of what you've lived through. You are taking true stories from your life and turning them into art. This is an art form for other people to enjoy.

It's true, but you are creating art. It's very different than chronicling your life. It took me a long time to learn that.

Joanna: Yes. Let's come back to this word “art,” but first of all, I want us to tackle structure because, okay, I also learned this the hard way.

When I wrote my travel memoir, Pilgrimage, I had like over a hundred thousand words of writing, and I just couldn't figure out how the structure of the book could work until I found another book that helped me figure out the structure.

Like, there are lots of different types of memoir structures and mine I found a sort of model and then I was like, oh, okay, this is how it works.

Talk us through how we can potentially structure a memoir.

Even if we're someone like me who might be a discovery writer first, or like you by the sound of it.

Wendy: Oh, well, absolutely. So I hate structure, right? And that's why I became an expert in it—in order to make it a lot easier for me to understand.

So I am not a planner, right? In fact, there's a line in my memoir about there are two different kinds of travelers. There are planners and there are fun people, right? So I've never been a planner in any aspect of my life. So the fact that I would become this expert in structure is kind of ironic.

Let me go back to this idea of structure. So I think when people talk about structure, their first thought is three acts. Or are you doing a dual timeline? How is the big picture? How is your book going to play out?

When I use the word structure, I am referring to how structure plays itself out in every sentence of your book. I mean, it's such a critical part of your story.

So there's global structure, which is really referring to how you're going to use chronology in your book, how you're going to tell this story, and then there is structure on every page of your book.

So what happened is I actually started teaching after my memoir got published. Several years later, I started teaching memoir writing, and teaching is very different than doing, right?

I wrote my memoir by a process of trial and error. Eventually, this agent did sign me and kind of helped me understand what wasn't working in the manuscript that I'd submitted, and I spent a year rewriting it. It eventually got published.

When I started teaching memoir writing, it was different because teaching someone how to do this is very different than this trial and error of doing it yourself. So as time went on, I would see the same mistakes over and over again.

I started to say, well, there are these categories of mistakes, and what if I reverse engineered this and kept people from making these mistakes? So in order to not make the mistake, there must be a principle that people need to follow. So that was the beginning of The Memoir Engineering System.

It took me 15 years to understand that —

Plot can be summed up in two words and it's connected events.

Now, why do I say that?

Well, the problem with memoir writing is that it's very tempting to feel like the things that you did—the things that you're including in your memoir—let's say it's a travel memoir.

So arriving in Paris and then going out to eat for the first time, and then walking down the Champs-Élysées, and then going to the Louvre. So I just mentioned several things that you might have done, that a person might have theoretically done in this memoir on Paris.

The problem with this from a reader's perspective is that this is not plot, and the reason it's not plot is that these things are not related to one another. So by relating them, it could be with an idea. What do all of these things have in common other than they are things that you did in Paris?

You need something a little deeper than that. You take these disconnected events—I went to the restaurant, I walked down the Champs-Élysées, I went to the Louvre—and you turn them into plot. So that really is the basis of everything I teach is that connected events equal plot.

A memoir writer's biggest challenge is taking all these things that they lived through, whether it's a travel narrative or different kind of narrative. It's a bunch of stuff that happened to you, and that's not plot.

How do you take a bunch of stuff that happened to you and turn it into plot? You let your reader know how these events are connected. So that's really the basis of what I teach. Does that make sense?

Joanna: Yes. Well, maybe give us a concrete example with your own memoir, Avoiding Prison and Other Noble Vacation Goals: Adventures in Love and Danger, which obviously are connected events. They would be vignettes, I imagine, about these different adventures.

What is the connected event? Is that more about you as the character or is it the theme?

Wendy: So this is called The Memoir Engineering System, right? I really believe that there was this hidden code underlying memoir. I promise I'm not avoiding the question, Joanna. I'm going to get to it in a second.

In order to explain how this works, what took me 15 years of reading over a thousand manuscripts to understand about how memoir actually is doing, how it actually works, is that there are two different components in your book. You have scenes and you have transitions.

In your scene, you have the building blocks of plot and something must happen. In your transition you have an idea that shows what happens in one scene is related to what happens in the next.

So in my own book, I didn't know this because I wrote this as a process of trial and error. If I were to go back to my made up example of, you know, I go out to eat on the Champs-Élysées and then I go to the Louvre, what do those things have to do with each other? Absolutely nothing. They're not related in any way.

But you can ask yourself is, what was I doing in Paris? What was I searching for? Maybe I was searching for a sense of understanding myself. I don't know, there's no one right answer, right? It's a fictitious example.

So in your transitions between your scenes, maybe this is a search for identity, maybe when you're outside of your own country, you understand yourself better.

So the transitions in that chapter would all be about identity and this idea of identity would infuse itself through your chapter and it would take these disconnected things you did and it would turn them into a story. Does that make more sense?

Joanna: Yes. I mean, I know what you mean because I think this is where people need to get more personal. I feel like you can write a travel guide, and when I started writing my pilgrimage books, I thought I was writing travel guides.

Then I realized I actually had a deeper sense of the whole thing. I was lost and I was trying to find myself and all that like you do at midlife. Seeking faith and all of that.

I think memoir only really happens when you get a lot more personal.

So as you mentioned there, sort of the idea that something happens, but it's your personal reflection and how your own personal transformation happens through the course of the book.

So you have to write at a much deeper level than you would if it was, say, just a travel guide about Paris.

Wendy: Oh, I think all memoir is more closely related to literary fiction than commercial fiction because you're never going to have the plot twists and turns of a detective novel, for instance. So it's really dependent on the depth of the prose, right? Your insights. That is why people read memoir.

So you need some plot, but you're never going to have those twists and turns and surprises and unbelievable suspense that you would have in commercial fiction. In that way, it's more like literary fiction.

So it's so dependent on the prose, so dependent on the insight, the quality of the prose, affecting your reader emotionally with your words. So I tell my clients structure is kind of black or white. It's either working or it's not. So don't stress over finding the best structure for your book.

Structure is there to keep your reader from being confused, to keep them from going, wait, I have no idea why you're telling me this after reading this scene. I've no idea why you're telling me about this other thing because they're not at all related.

Structure is there to keep your reader from being confused. What makes them actually love your memoir is the quality of your prose affecting them emotionally, your insight, your point of view, how subjective your writing is.

Joanna: So what are some tips for people who are finding it difficult to get down to that depth? Because it is very difficult. I found writing memoir much more difficult than fiction, and I've written lots of other kind of self-help nonfiction. You really do kind of have to bare your soul.

What are some of your tips for people to write at a much deeper level?

Wendy: Well, so what I suggest, even though I hate planning, is that people start with an outline, but a very specific outline that really consists of figuring out what their scenes are. Now, this outline can change along the way, but starting with an outline so that they ask themselves, okay, what is each scene about?

When I've had people do that, the process of writing becomes so much easier because structuring your book is a very logical process. Writing your book really is this creative process. That's the part I love. I love the creative part. I don't love the structuring part.

But when faced with the choice, okay, you can spend seven years writing and rewriting and figuring this out by trial and error, or you can spend a month of your life creating this outline and then finish your memoir in a year, somehow that investment of time starts to seem worth it.

So when it comes to actually writing, I find that any kind of writer's block, I find the reason that prompts work, I think, is that you push against limitations and that actually makes me more creative.

So I found that having the structure for my book before I start writing actually makes it so much easier to write and it makes me more creative.

If I have this outline for the book and I don't feel like writing that depressing scene about that time I got in this argument with my mother, I feel like writing this fun scene over here because I'm in a funny mood today, I can do that because I have a sense of what the book is like globally.

So I really do believe in outlines, even though I hate actually creating them. I think it makes it easier to write. I think it makes it actually more fun to write once you've gotten through the drudgery of creating this outline.

Joanna: Yes, I must say, because like I said, I'm a discovery writer. I've never ever written a book with an outline. With my book Pilgrimage, I hadn't finished the character arc until I had done three pilgrimages.

I feel like perhaps your method is more suitable for people who already have an idea of their story in mind.

Like they've already finished their transformation, whatever that may be, or that period of their life that they want to write about.

Whereas I think when I started writing, I still hadn't found the meaning. I guess I hadn't found the, what you are calling the idea in each of the scenes.

Wendy: So I do take a really different approach than most memoir coaches. So what you're talking about, your character arc, I actually find the easiest part of any memoir, and I'll explain why in a second. Plot is difficult. Plot requires thinking and figuring out your plot.

For me, your character arc is synonymous with the theme of your book. Is it about belonging? Is it about identity? Is it about coming to terms with your childhood?

I find that that actually comes out in the writing itself because that is the theme of your life, and I think that is so much a part of everything you do and everything you write, that it comes out in the writing itself.

That to me is the easiest part of writing a memoir, is this character arc, this internal journey, and that is one of the few things that doesn't require structure because it's in the writing itself. Now there's a little bit of thought that goes into it, but I honestly find one of the easiest parts of writing a memoir.

What is actually difficult is taking a bunch of things you did in a country and connecting—this day I did this, and the next day I did this, and the next day I saw this place, and the next time I met this person.

All of that will bore your reader to tears if you don't connect these events in some way, and if you don't make them related to one another to tell a story. Otherwise you're just telling them a bunch of stuff you did and you're a stranger to them and they don't care.

If you take all of these things you did and you connect them in some way, usually with an idea—usually with some thematic idea—you are creating plot in that chapter. That's really a challenge for memoir because we don't have the advantage of making things up as a novelist does.

Joanna: Yes, we should tackle the making things up aspect because you've used language like character arc, you've used plot, you've said it is more similar to literary fiction, so you have used a lot of fiction language.

So where is the line for truth? People might know of The Salt Path controversy, which is—if people don't know—a travel memoir which is a lot of truth, but some quite core things have been challenged in the press. So there's sort of been a feeling of betrayal by people who loved that memoir.

What are some of the lines around truth with writing memoir?

Wendy: I honestly think the bar is pretty low in the sense that the people who are getting in trouble—and this is not the first time a memoirist has been in trouble for fabricating facts of their life—it kind of is shocking to me, right?

So I would say that all memoirs take some license, and so there's this ethical continuum and you have to feel comfortable with it. So I tell people you need to put a disclaimer in your book.

Most memoirs will play a little bit with the order of events. Now, when I'm saying that, what I mean is that I might have had a really funny conversation with my mother in October, and in the book it comes in March because that's a perfect place to put this conversation in my book.

I don't think that is being unethical, and I would also put a disclaimer in the beginning of my memoir that I have sometimes changed the chronology of the book.

Now making up huge things that never happened—so one thing I tell people I work with is I would never make up something happening.

So I had this conversation with my mother. I may not remember the dialogue exactly, but it's to the best of my memory, it's my representation of that moment in time, but I would never make up something happening.

The memoirs who are getting in trouble—so this is not the first time a memoirist has been in trouble—but all of the ones who've really had these public scandals have made up huge things.

So I don't think it's a complicated issue, to be honest with you. I think all memoirs take some license. The ones who get in trouble kind of deserve to get in trouble because these are big things they're making up. I'm thinking James Frey, do you remember James Frey?

Joanna: Yes. Was it A Million Little Pieces?

Wendy: I think that's what it was. Yes. I mean, I think Augusten Burroughs got in trouble too. There've been many cases, but people were making up big chunks of their life. They weren't moving things around in time.

Joanna: I agree, but it is hard because, for example, if people are writing something from a long time ago. So I guess I was shocked at the end of Cheryl Strayed's Wild, because suddenly it's kind of revealed at the end that she's writing it decades later.

My first thought, I think it was one of the first memoirs I kind of read, and I was like, well, how can you remember those conversations? How can you write dialogue as if it was last week?

In my own memoir, like I wrote while I was doing my pilgrimages. Over three years, I was writing journals and I wrote the book very soon after. But a lot of people do write memoir from decades ago, so how do we keep that line?

Also, I wanted to ask you, you mentioned your mother as well. A lot of people are putting family members or people they met or whatever into books.

How do we make sure that our memory of something is right?

Wendy: Oh, that's a much harder question, Joanna. Okay, to answer your first question, how do you recount dialogue? Let's say you're writing 30 years later and you're trying to recount what someone said. You do the best you can.

What I want to say is that people who are getting in trouble, famous memoirs getting in trouble, are not getting in trouble because their mother comes back and says, “You know, I didn't say exactly that 20 years ago.”

They're getting in trouble for making up big things, making up illnesses that they didn't have, making up criminal records that they didn't have. So these are big things that can be fact checked. That's what people get in trouble with.

I have never heard of a memoir getting in trouble because a family member said, “Well, I think the conversation was different.” Ever, have you? So we're talking that's a whole different level and you do the best you can. So that is not an issue for me. I have an issue with people who make up facts.

I'm doing the best I can to remember dialogue, and if I don't remember dialogue, I don't put it in my book. You don't need tons of dialogue in your book. What you need is great point of view, great prose in your scene to make it engaging to a reader.

Joanna: Yes, that's true. But on the family thing, it's more like—

“Well, you portrayed this situation this way, and I don't feel like it happened like that.”

Wendy: That is really difficult, right?

So first of all, one of the things I teach memoirs is that it's really important to give us a point of view. I think some of my hardest clients are journalists. They've been taught to be objective. Objective, just the facts, right? That is not what a reader wants from memoir.

We really want this point of view. It's really ironic that in being incredibly personal, you actually make your story universal. It's the only way I know to make your book universal is being so personal that I see myself in the story.

So we need that point of view, and your point of view may be very different than your mother's point of view. That's true, right? I mean, life is that way. So you do need to be faithful to your point of view.

Now, having said that, you are writing about real life people and there are repercussions. Your mother may come back to you and say, “I'm never speaking to you again. How dare you portray me that way?” I mean, it depends on your relationship with the person, but it is something to consider.

So that, to me, is a very different question. I always write my truth. Now, once I've finished writing my truth and my point of view, I go through my memoir and I say, well, whose opinion do I really care about? Is my mother going to be so devastated by this that I'm going to damage my relationship and is it worth it?

So there were some people in my book, I'm like, oh, this person's going to hate what I said about them. I don't care. I don't even like this person. So I left it.

With my mother, for instance, I said, “Well, mom, I'm going to tell you, this memoir is coming out.” This was a long time ago, by the way, kind of like Cheryl Strayed, right? So long time ago. a

I said, “Well, I say a lot of things about you, but we really needed this conclusion at the end. And in the end, this really turns out to be this character arc about understanding my relationship with my mother even better. So in the beginning, we needed lots of conflict to get there.”

Totally true, but a little out of proportion so that my mother would let me get away with talking about some of the things she probably didn't want me talking about. She took this really well, and the way I handled it was I had her read the last chapter first, where she really does come across really great, right?

I know my mother incredibly well, and I also knew what would work with her. So she loved the publicity. She would do book readings with me. She went on television with me. She hammed it up in book readings. She would read her lines in the book. So it actually brought us closer together.

My father is very different. My father does not like publicity. I knew if I had said anything negative about my father, he wouldn't speak to me again, and so I didn't.

So it wasn't that I lied, but I did take into consideration the relationship I had with my parents. They are different people and I knew they would take it in different ways. So that is a real life consideration that you do need to take into account.

Joanna: Well, I think that's very respectful of you for both of them, and the most healthy way to do things for sure.

I think another thing that happens with memoir is people have far more damaged relationships than you clearly had. I think some people want to use memoir as a form of therapy or revenge. That's another thing. Revenge, rage, anger, and a very negative emotion.

So absolutely people need to write their truth in at least the first draft, but where do you think the line is between therapy and what could be conceived?

What could go very, very wrong for both the person writing and also anyone on another side?

Wendy: I think a lot of people want to write their memoir for the sake of therapy and in the end, that's really fine. I've always wanted to be a published writer.

I care about having an audience. I care about saying the truth. My truth, obviously not the truth. I care about saying my truth and creating art for an audience, and that really is a different consideration than journal writing, which is for yourself.

So if you are writing a memoir for an audience, you are writing it in a different way. So what I would say to people full of trauma and anger—yes, plenty of trauma, let me tell you, right? Plenty of trauma in my memoir as well. Even though it's a humorous book, there's plenty of trauma in there.

What I would say is that it depends on the tone you use. Let me give you an example of just talking to another human being, a stranger. If you start to talk to that stranger and they're like, “My life has been so unfair, nobody has ever given me a chance,” do you really want to talk to that stranger?

So it's a matter of tone. If that stranger says, “I have gone through so much. I was abused as a child, I suffered poverty and homelessness. Let me tell you what I've come away with.” You kind of want to lean in and you're like, “Well, tell me about being homeless.” You want to hear that story.

So it's not what you've lived through. I think it's where you are in dealing with this. So if you are still processing trauma, and you're at the stage where life is unfair, and you know, I've given up, you probably are not ready to write a memoir for other people yet.

Feel free to write to process that trauma, but if you're writing for a public, we want to learn through what you've lived through. Living through someone else's difficulties can be really therapeutic for your reader as long as you're on the other side of them.

There's a Tobias Wolff quote, and I'm not going to get it wrong—I'm paraphrasing it—but I heard this on an NPR radio interview many, many years ago. He was being interviewed, I think it might've even been for This Boy's Life. So that would've been a long time ago. He said,

“You should write about what has hurt you the most, but only after it's quit hurting you. So then you have that perspective. You have that wisdom.”

Joanna: Yes. I mean having written journals through dark times in my life, and then looking at it later, when you are going through these things, your writing is really repetitive and quite frankly, boring.

Wendy: “Poor me, life is so hard,” and that's okay. It's okay in the moment.

Joanna: Yes, but as you say, nobody wants to read a repetitive journal over and over again. That's not a memoir. So it is difficult, isn't it, to find that line between sharing enough and then not being repetitive. I feel like this is where you have to keep the audience in mind. It's like, okay—

That was good for me as a writer, but what's good for the reader?

Wendy: It is, and it really depends on your goals as a writer. It really does. Both are valid. If you are writing to heal from trauma, that is a really valid reason to write. It works. It really does work to write to heal from trauma.

If you're writing for an audience, it is a different level. You might have to leave some things out of your book that really mattered to you. You are trying to take true events from your life and turn them into plot, so it is a different goal.

Joanna: Well, let's just talk about that then. Definition of success is so important and I think with every genre there are books that hit big.

So everyone thinks they're going to be Cheryl Strayed with Wild, and everyone did want to be like The Salt Path until quite recently. These books that become mega, mega bestsellers and have movies.

Should authors expect to make money with memoir, or how could success be defined?

Wendy: It really depends on how badly you want to be financially successful when it comes to writing. Let me qualify that just a little bit. So if you really care about making money, what you do need to learn is marketing and publicity. So a huge portion of your time is going to be spent getting publicity for your book.

So what makes for a successful book, I think is three things. It's writing a book that readers love. Not every reader—some people are going to hate your book. In fact, that's actually a good sign. Not everyone needs to love your book.

Some people need to love it, some should hate it. That means you've written a book that actually says something.

So you need to have written a good book. You need publicity because if no one hears about this really good book you've written, it's not going to be financially successful. And then you need luck.

So I think the Cheryl Strayeds, the Wilds of the world, also had a little bit of luck. So you can control it to a certain extent if you are willing to put in the work to do marketing and publicity on your book.

I think you could count on a modest success if you're willing to work hard on it, because the reality is, if you care about making money off of your book, the money comes from publicity and marketing.

If you don't, and you're writing a book and you've put it out in the world and it's beautiful and you want to see what happens and who finds it, and that is your satisfaction, that's valid too. It just depends on what your goals are.

If you want to make money off of a book, there really is this whole publicity and marketing side of it. That's just the reality because there are books out there, and if no one has heard of your book, no one's going to buy it.

Joanna: And that's true for all books.

Wendy: Yes, unfortunately. We hate that, right, Joanna? Don't you hate marketing?

Joanna: Oh, nobody wants to do it, but it just has to be done.

I think what's interesting about memoir though, which is a very good thing, is that it's kind of timeless. So I really think that like my memoir, Pilgrimage, and like your memoir, we can talk about them for the rest of our lives because they are part of life at a point.

Obviously there'll be other books that we write about different parts of our life, but to me it's far more timeless than other genres. I mean, you mentioned marketing. I have a book called How to Market a Book, and it's on its third edition. It needs updating all the time because marketing changes, but—

Memoir is evergreen.

Wendy: It's evergreen. Absolutely. Absolutely. Yes, though I do have to say that I wrote my memoir in my twenties though. It's been 30 years—I whisper that to you, right? So I think I wrote my truth then.

If I were to write about the exact same experiences, I would write about them in such a different way, and not in a better way. Just a different way. Hindsight is 20/20.

Joanna: Yes, but I feel like there are different times of our lives, so I feel like I will write another memoir at some point, but it won't be about pilgrimage, it'll be about something else.

Wendy: What is it going to be about? Do you know?

Joanna: I don't know yet. I haven't lived it yet. I think it will appear. Although, I've got this book around gothic cathedrals that I started out as a photo book and now it's kind of turning into half a memoir. Because I'm a discovery writer, I don't even know what happens until these things arrive.

Wendy: Fair enough. If you ever want help with an outline, you call me and I will help you with your outline.

Joanna: Fantastic. Well, tell us—

Where can people find you and your books and courses online?

Wendy: I think the easiest way to find me is to go to GeniusMemoirWriting.com and you can find information about The Memoir Engineering System, which is my book on memoir structure. My own memoir's called Avoiding Prison and Other Noble Vacation Goals. Or just Google Wendy Dale.

I also have a YouTube channel, so Google Wendy Dale and you'll find lots of stuff.

Joanna: Brilliant. Well, thanks so much for your time, Wendy. That was great.

Wendy: Thank you so much, Joanna.

The post Why Structure Matters More Than You Think. Writing Memoir With Wendy Dale first appeared on The Creative Penn.