Show Notes

Overview

- Blunt neck trauma comprises 5% of all neck trauma

- Mortality due to loss of airway more so than hemorrhage

Mechanism

- MVCs with cervical hyperextension, flexion, rotation during rapid deceleration, direct impact

- Strangulation: hanging, choking, clothesline injury (see section on strangulation in this chapter)

- Direct blows: assault, sports, falls

Initial Management/Primary Survey

- Airway

- Evaluate for airway distress (stridor, hoarseness, dysphonia, dyspnea) or impending airway compromise

- Early aggressive airway control: low threshold for intubation if unconscious patient, evidence of airway compromise including voice change, dyspnea, neurological changes, or pulmonary edema

- Assume a difficult airway

- Breathing

-

- Supplemental oxygen

- Assess for bilateral breath sounds

- Can use bedside US to evaluate for pneumothorax or hemothorax

- Circulation

-

- Assess for open wounds, bleeding, hemorrhage

- IV access

- Disability

-

- Maintain C-spine immobilization

- Calculate GCS

- Look for seatbelt sign

Secondary Survey

- Evaluate for specific signs of vascular, laryngotracheal, pharyngoesophageal, and cervical spinal injuries with inspection, palpation, and auscultation

- Perform extremely thorough exam to evaluate for any concomitant injuries (e.g. stab wounds, gunshot wounds, intoxications/ ingestions, etc.)

Types of Injuries

-

-

- Carotid arteries (internal, external, common carotid) and vertebral arteries injured

- Mortality rate ~60% for symptomatic blunt cerebral vascular injury

- Mechanism

- Hyperextension and lateral rotation of the neck, direct blunt force, strangulation, seat belt injuries, and chiropractic manipulation

- Morbidity due to intimal dissections, thromboses, pseudoaneurysms, fistulas, and transections

- Clinical Features

- Most patients are asymptomatic and do not develop focal neurological deficits for days

- if Horner’s syndrome, suspect disruption of thoracic sympathetic chain (wraps around carotid artery)

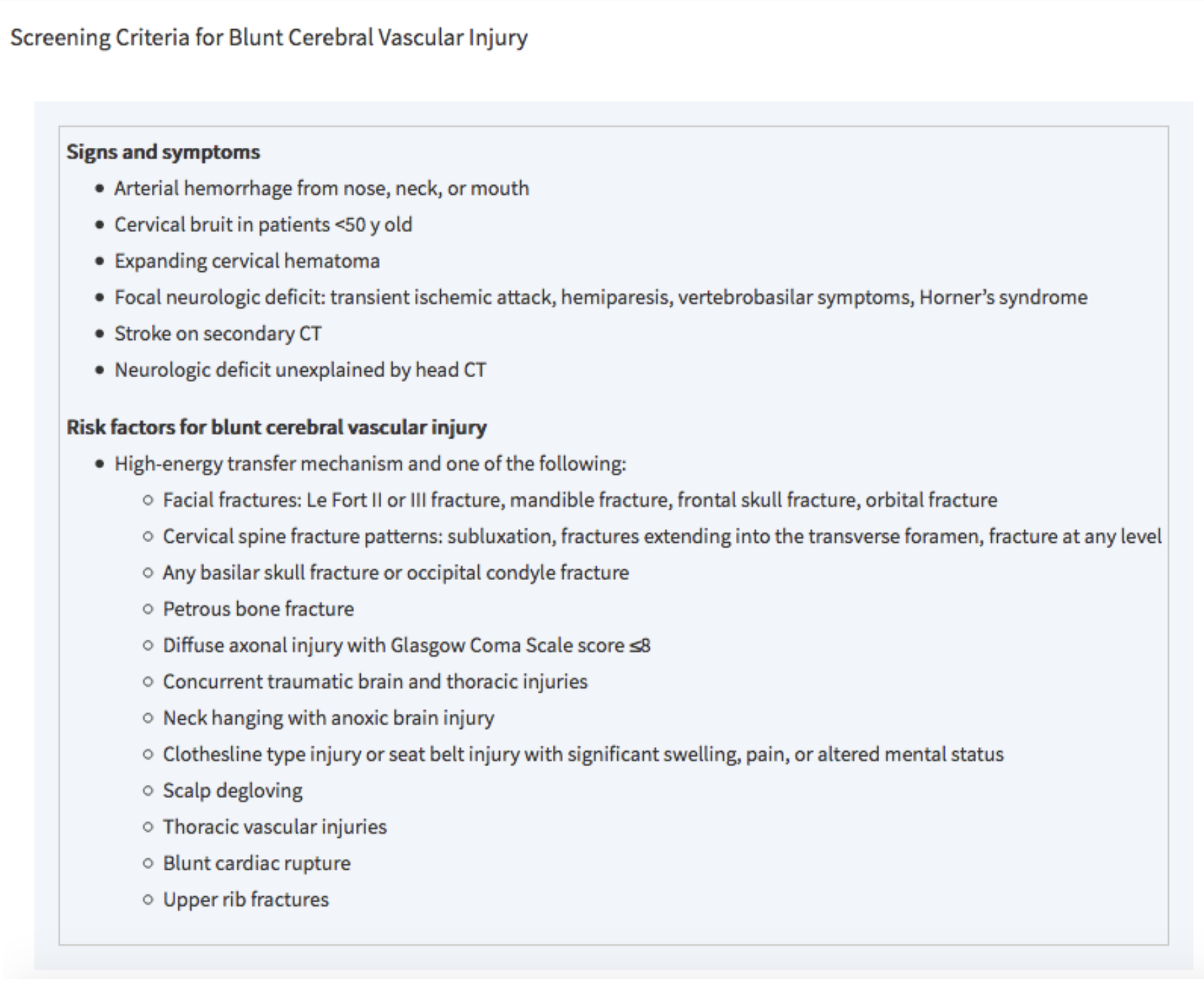

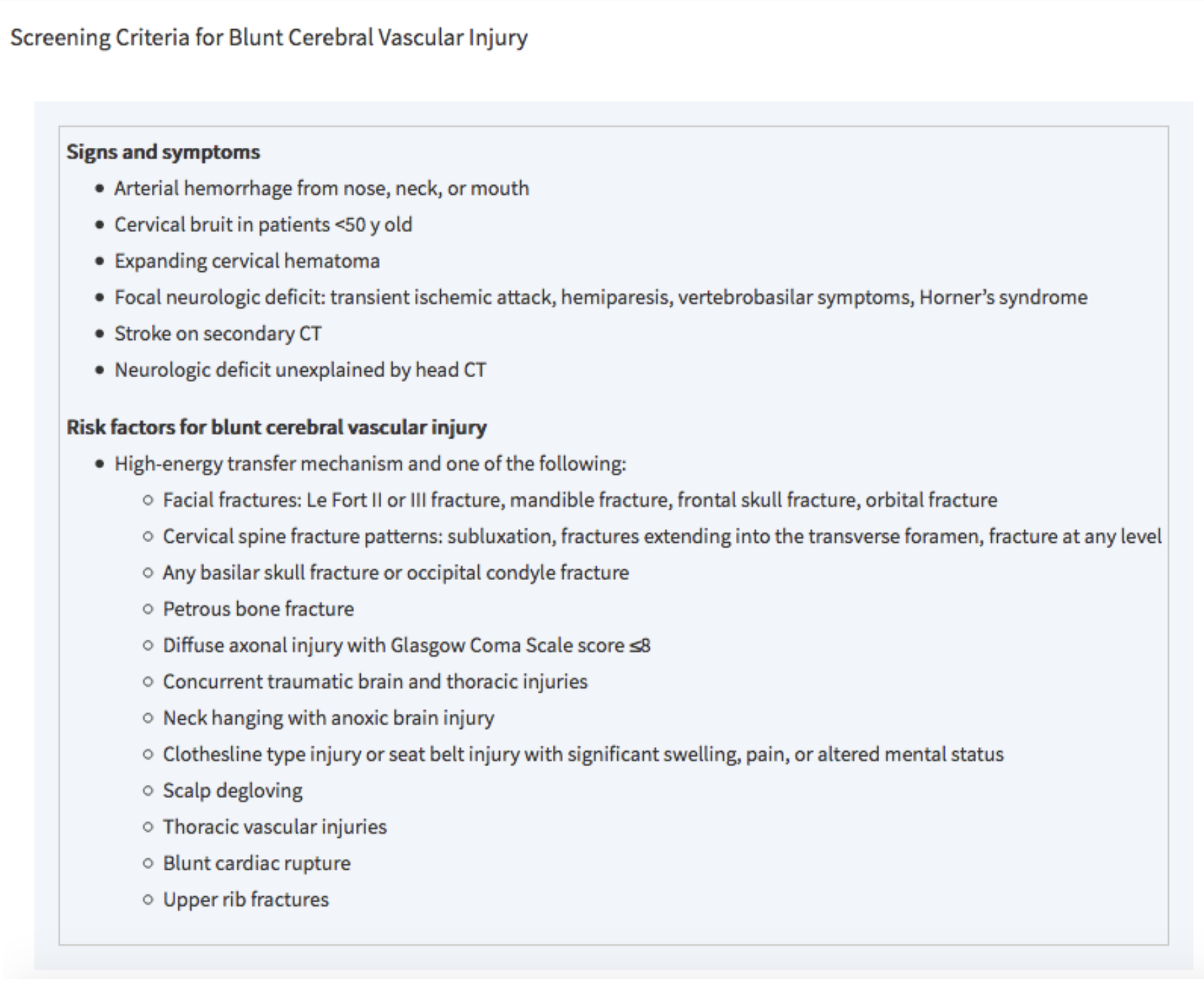

- specific screening criteria are used to detect blunt cerebrovascular injury in asymptomatic patients (see below)

Tintinalli 2016

- Diagnostic Testing

- Gold standard for blunt cerebral vascular injury = MDCTA (multidetector four-vessel CT angiography)

- <80% sensitive but 97% specific

- Also images aerodigestive tracts and C-spine (unlike angiography)

- Followed by Digital Subtraction Angiography (DSA) for positive results or high suspicion

- Angiography is invasive, expensive, resource-intensive, and carries a high contrast load

- Management

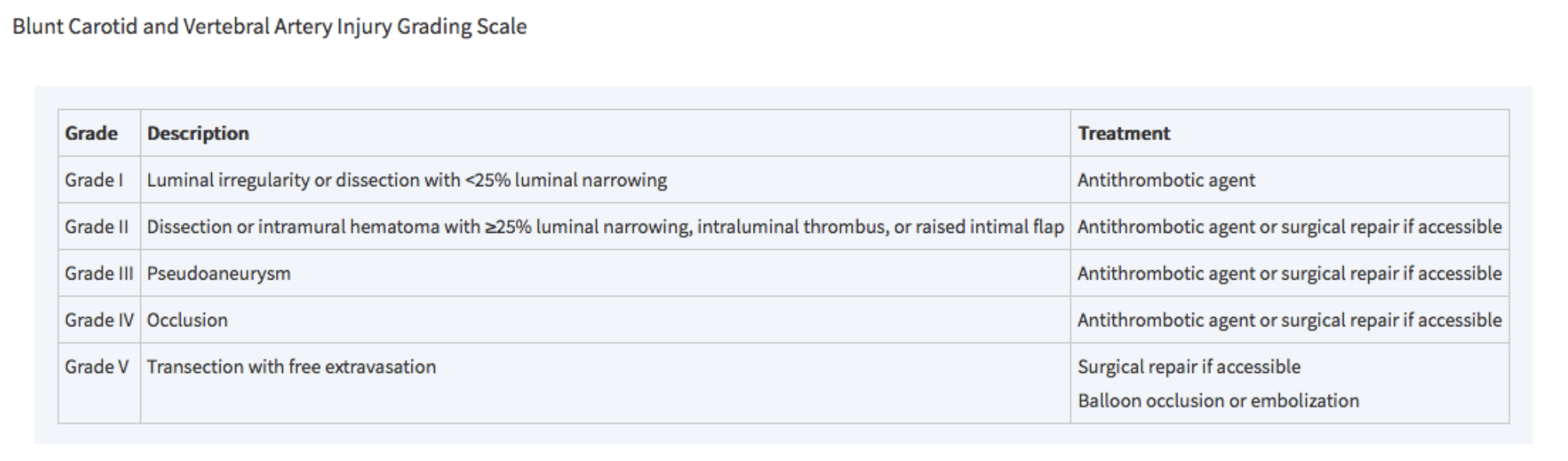

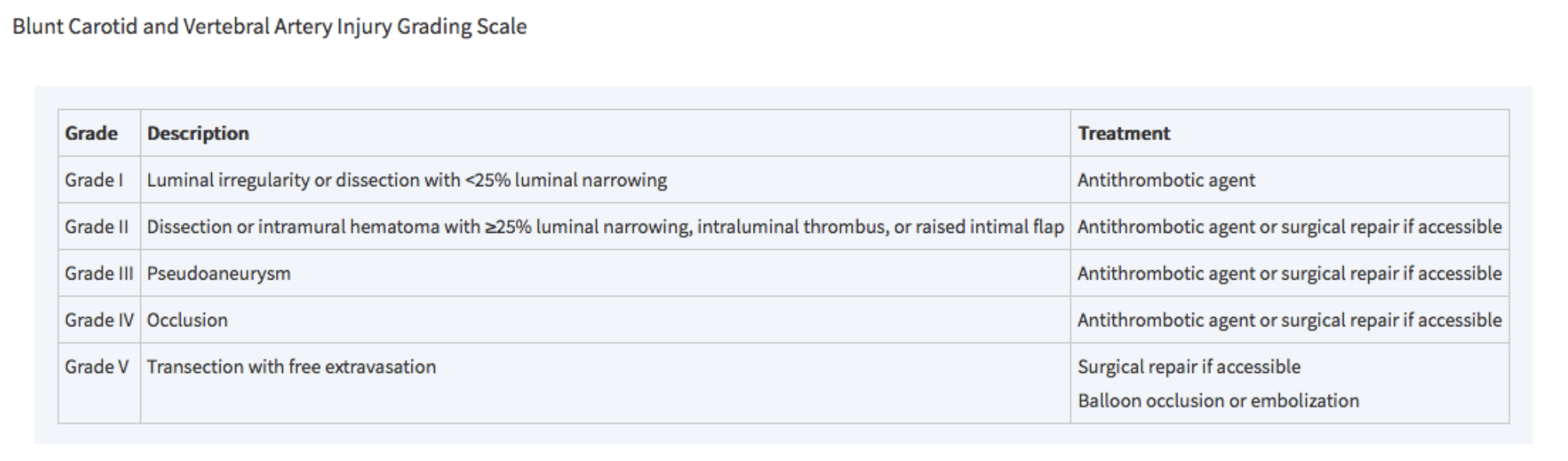

- Antithrombotics vs. interventional repair based on BCVI grading system

- Involve consultants early: trauma surgery, neurosurgery, vascular surgery, neurology

- All patients with blunt cerebral vascular injury will require admission

Tintinalli 2018

- Pharyngoesophageal injury

-

-

- Overview

- Rare in blunt neck trauma

- Includes hematomas and perforations of both pharynx and esophagus

- Mechanism

- Sudden acceleration or deceleration with hyperextension of the neck

- Esophagus is thus forced against the spine

- Clinical Features

- Dysphagia, odynophagia, hematemesis, spitting up blood

- Tenderness to palpation

- SC emphysema

- Neurological deficits (delayed presentation)

- Infectious symptoms (delayed presentation)

- Diagnostic Testing

- Esophagography with water-soluble contrast (e.g. Gastrograffin)

- If negative contrast esophagography, obtain flexible endoscopy (most sensitive)

- Combination of contrast esophagography + esophagoscopy has sensitivity close to 100%

- Swallow studies with water-soluble agent

- MDCTA

- Plain films of neck and chest

- Findings such as pneumomediastinum, hydrothorax, or retropharyngeal air may suggest perforation but are not sensitive

- Management

- All pharyngoesophageal injuries receive IV antibiotics with anaerobic coverage

- Parenteral/ enteral nutrition

- NGT should only be placed under endoscopic guidance to avoid further injury

- Medical management vs. surgical repair depending on extent of injury

- Surgical repair for esophageal perforations or pharyngeal perforations >2cm

- Involve consultants early: trauma surgery, vascular surgery, otolaryngology, gastroenterology

- All patients with blunt cerebral vascular injury will require admission

- Laryngotracheal injury

-

- Overview

- Occurs in >0.5% of blunt neck trauma

- Includes hyoid fractures, thyroid/ cricoid cartilage damage, cricotracheal separation, vocal cord disruption, tracheal hematoma or transection

- Mechanism

- Assault, clothesline injuries, direct blunt force from MVCs compressing the larynx between a fixed object and the spine

- Clinical Features

- Patients are often asymptomatic at first and then develop airway edema and/or hematoma resulting in airway obstruction

- Children are at higher risk for airway compromise due to less cartilage calcifications

- Diagnostic Testing

- Flexible fiberoptic laryngoscopy (FFL) to assess airway patency and extent of intraluminal injury

- MDCTA

- Obtain 1-mm cuts of larynx and perform multiplanar reconstructions

- Consider POCUS to detect laryngotracheal separation

- Plain films of neck and chest

- Poor sensitivity for penetrating neck trauma injuries

- Can show extraluminal air, fracture or disruption of cartilaginous (e.g. larynx) structures

- Management

- When securing airway, use an ETT that is one size smaller due to likelihood of airway edema

- Conservative management (IV antibiotics, steroids, observation) vs. surgical repair

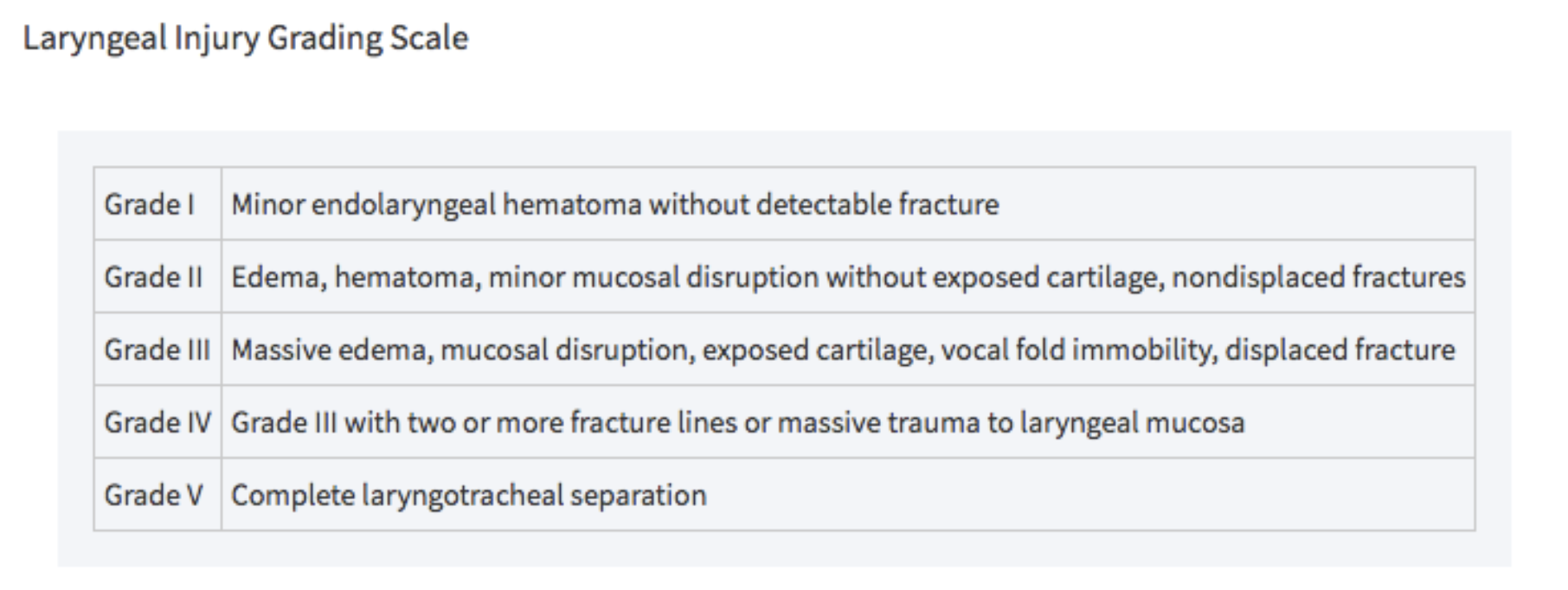

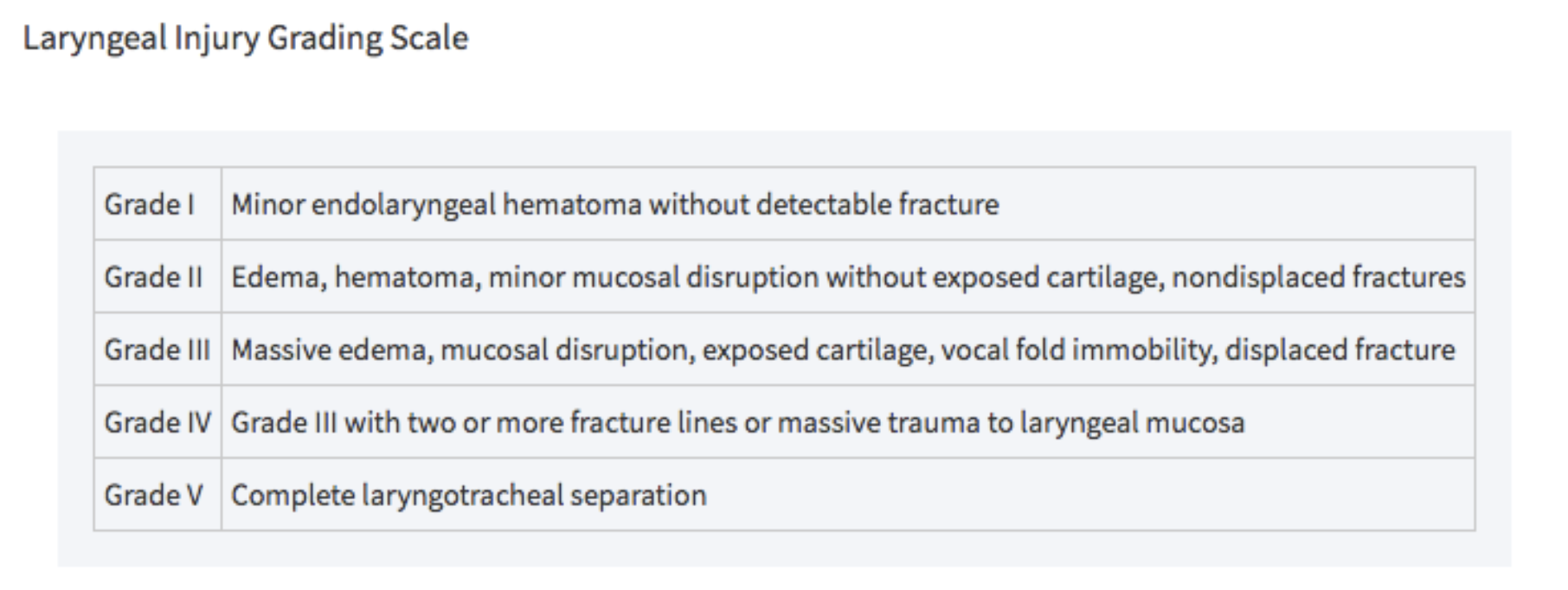

- Grades III, IV, and V laryngotracheal injuries as defined by Schaefer and Brown’s classification system require OR

Tintinalli 2018

Tintinalli 2018

-

-

-

- Involve consultants early: trauma surgery, neurosurgery, vascular surgery, neurology, otolaryngology

- Cervical spine/ spinal cord injury

-

- See chapter for spinal trauma

Disposition

- Admit symptomatic patients to monitored setting

- Given delayed symptoms, consider monitoring patients who are asymptomatic on arrival

- Serial exams for worsening dyspnea, dysphonia, stridor, drooling, bruits, focal neuro deficits

- Only discharge after ruling out airway threat, neurological deficit, vascular injury, or suicidal/ homicidal ideation

- Monitor asymptomatic patients on home anticoagulation in ED for at least 6 hours from trauma to rule out delayed neck hematoma

- Social work and/or psychiatry for patients in whom you suspect suicide risk or domestric violence, look for other signs of self harm

Take Home Points

- Aggressive early airway management for unconscious patient, evidence of airway compromise including voice change, dyspnea, neurological changes, or pulmonary edema

- Involve consultants early: trauma surgery, neurosurgery, vascular surgery, neurology, otolaryngology

- Victims of blunt cerebral vascular injury may present completely asymptomatic but develop delayed neurological symptoms; close observation and monitoring is recommended especially for patients on home anticoagulation

- Remember to evaluate for concomitant injuries

- Psychiatric evaluation for all attempted suicides

References

- Bromberg, William. et al. Blunt Cerebrovascular Injury Practice Management Guidelines: The Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma. J Trauma. 68 (2): 471-7, Feb 2010.

- Cothren CC, Moore EE, Biffl WL, et al. Anticoagulation is the gold standard therapy for blunt carotid injuries to reduce stroke rate. Arch Surg. 2004;139:540–545; discussion 545–546.

- Joshua AA. Neck Trauma, Blunt, Anterior. In: Schaider J, Barkin R, Hayden S, Wolfe R, Barkin A, Shayne P, Rosen P. Rosen and Barkin’s 5-Minute Emergency Medicine Consult. 5th Edition. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer; 2015; 738-739.

- Tintinalli, J., Stapczynski, J. Stephan, editor, Ma, O. John, editor, Yealy, Donald M., editor, Meckler, Garth D., editor, & Cline, David, editor. (2018). Tintinalli’s emergency medicine : A comprehensive study guide (9th ed.).

- Walls, R., Hockberger, Robert S., editor, & Gausche-Hill, Marianne, editor. (2018). Rosen’s emergency medicine : Concepts and clinical practice (Ninth ed.).

- Advanced trauma life support. (2018). 10th ed. Chicago, IL: American College of Surgeons.

Special thanks to Sana Maheshwari, MD

NYU Bellevue Emergency Medicine Residency PGY3

Tintinalli 2018

Tintinalli 2018